In the 100th anniversary year of the Armistice (11 November 1918) Britten’s War Requiem, has a particular significance. It is not only a monumental work which commemorates the dead, but one that includes the poetry of the war poet Wilfred Owen who was killed in World War I seven days before the Armistice. There are, perhaps not surprisingly, many performances of the work taking place throughout the world (see the Google map at the bottom of this page), including at Coventry Cathedral on 14 November. This same Cathedral hosted the premiere of the work on 30 May 1962 not long after it had been constructed, and after its consecration there was an accompanying Festival of the arts of which War Requiem was a major element. The old Cathedral had been bombed in the blitz in November 1940, so the premiere performance remembered not only the dead of the First World War, but the Second as well.

Below: Britten and Meredith Davies rehearsing in Coventry Cathedral in advance of the premiere.

Britten composed the piece in 1961 while living at The Red House in Aldeburgh. In the previous 15 years he had been much preoccupied with operas: between Peter Grimes (1945) and A Midsummer Nights’s Dream (1960) he composed another eight operas. He brought his years of experience writing dramatically for voices into the visual and aural spectacle of this mighty choral work. War Requiem is certainly vast in its scale, as well as in its historical (and political) associations. It is scored for full chorus, with soprano solo, accompanied by a huge orchestra; a separate chamber orchestra sits alongside accompanying the tenor and baritone soloists; and there also is a children’s choir and organ, often performing from a physical remove from the other players and singers. In early performances of the work – and sometimes still today – two conductors were used, one for each of the orchestras (and on many occasions a third conducting the children’s choir).

The main choir, soprano and orchestra perform the ‘Latin’ sections: the Requiem Mass for the Dead. This is the more conventional aspect of the work, in that Britten is following in the tradition of Mozart and particularly Verdi, who also composed Requiem masses. The male soloists, with their chamber orchestra, perform the Wilfred Owen texts. These are highly-charged, powerful verses by the soldier-poet, which stand aside from, and are sometimes directly at odds with, the religious texts of the mass. The music for these sections is less ‘grand’ than the Latin sections: more personal to Britten, and more akin to his own musical style at the time. The children’s choir sections are ethereal and haunting and used to poignant effect throughout the piece, particularly when the focus is on the horrific loss of young life. The combined forces only perform together once: towards the end of the piece, when they join together before the final ‘Requiem aeternam’.

Below: Britten with soprano Heather Harper in Coventry Cathedral.

The performers at the premiere were the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra and Coventry Festival Chorus (conducted by Meredith Davies), the Melos Ensemble (conducted by Britten), and the boys of Holy Trinity, Leamington and Holy Trinity, Stratford. The soloists were carefully chosen, although were not all Britten’s first choices. He deliberately wanted to have soloists representing three countries involved in the most recent conflict: a British tenor, Peter Pears; a German baritone, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, and a Russian soprano Galina Vishnevskaya. However, the Soviet Minister for Culture at the time would not allow Vishnevskaya to take part (‘how can you,’ wrote Ekaterina Furtseva, the Minister of Culture, to Vishnevskaya ‘a Soviet woman, stand next to a German and an Englishman and perform a political work?’ ). Heather Harper, at very short notice, stepped in for the premiere. Vishnevskaya was, however, permitted to take part alongside Pears and Fischer-Dieskau in the Decca recording a year later.

Below (scroll through): rehearsal photographs taken in Coventry Cathedral (Pears, and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau); and Britten with Galina Vishnevskaya during the Decca recording in 1963.

Even before the premiere, War Requiem was hailed as a masterpiece (‘There is no doubt at all, even before next Wednesday’s performance, that this is Britten’s masterpiece’, wrote William Mann in The Times, 25 May 1962). And despite some problems in the first performance – the choir in particular struggled a little with the new music – the reviews were generally very positive. The 1963 Decca recording sold over a quarter of million copies in a matter of months, topped the classical charts in several countries, and received two Grammy awards. After War Requiem, Britten did not write a work for such huge forces again. It was probably the most ‘public’ piece he ever composed: a high-profile commission, a huge popular success, and the most forthright statement he ever made regarding lifelong commitment to pacifism.

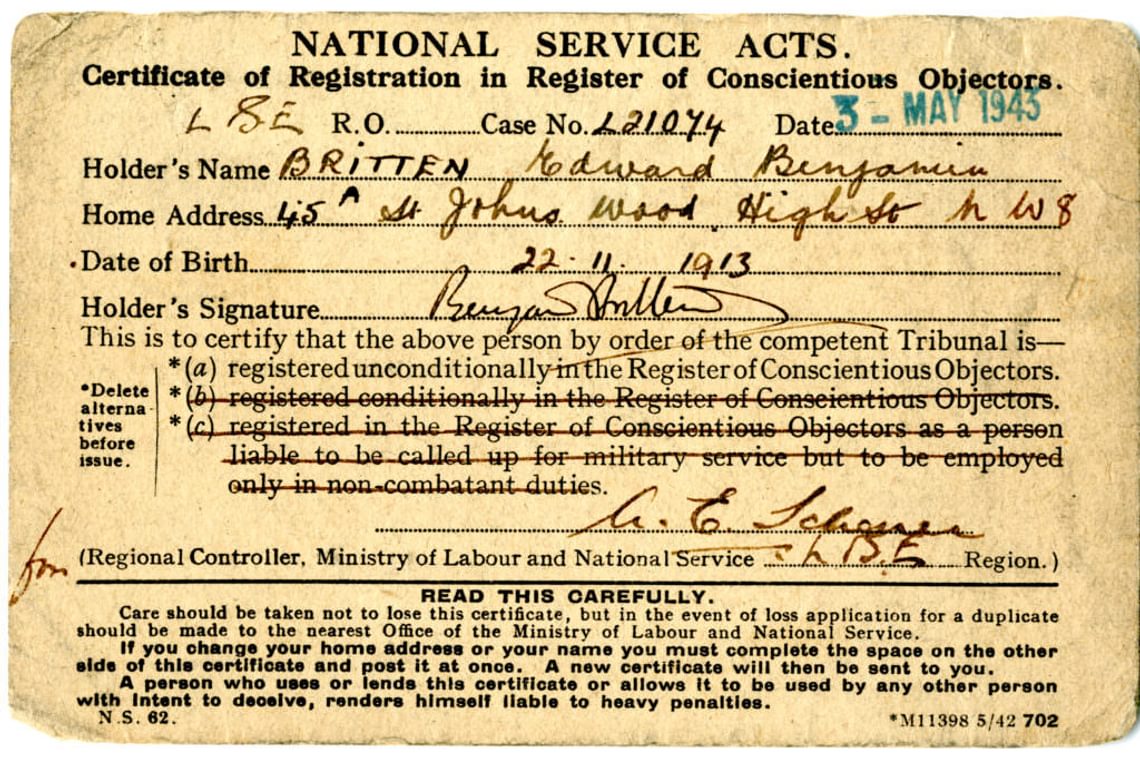

As the certificate above shows, he had registered as a Conscientious Objector in World War II, and prior to that had been a member of the Peace Pledge Union. For the rest of his life he regularly contributed to causes in pursuit of peace, such as CND. Juxtaposing Wilfred Owen’s poetry, much of it directly critical of the decision-makers in the First World War, with the Latin Mass was a political and potentially controversial act. Despite the coming together of all the forces at the end of the work, there is no easy resolution at the end of the piece – as Mervyn Cooke has put it:

It would have been tempting, and not uncathartic in effect, for Britten to have prolonged this serene envoi until the very closing bars of the War Requiem. But to do so would leave the listener far too comfortable, perhaps even complacent, about the fundamental issues, paradoxes and contradictions which this great work has addressed in the course of its eighty-five minutes. There are no clear-cut answers to the eternal problems of war and peace… (from Britten: War Requiem, edited by Mervyn Cooke (Cambridge, 1999))

As the twenty-first century continues there are seemingly still no answers to these problems: War Requiem remains as relevant today as it was in 1962.

Below: Britten in Coventry Cathedral.

Anthem for Doomed (Dead) Youth

Alex Jennings reads ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’

Stephen Johnson describes what is going on musically in this part of War Requiem

Listen to the full movement from Britten’s 1963 Decca recording

Find out more

See Britten’s composition draft (British Library Add. Ms 60609) of this section of the piece here.

Discover more about War Requiem by visiting http://warrequiem.org.

74th Aldeburgh Festival

09 – 25 June 2023

A Song at The Red House: 'Tell me the Truth About Love', by Benjamin Britten

Soprano Elise Caluwaerts performs one of Britten's cabaret songs, with a witty text by WH Auden. Accompanied by Lucy Walker on Britten's Steinway piano…

Work of the Week 24. Violin Concerto

Presented by Roger Wright