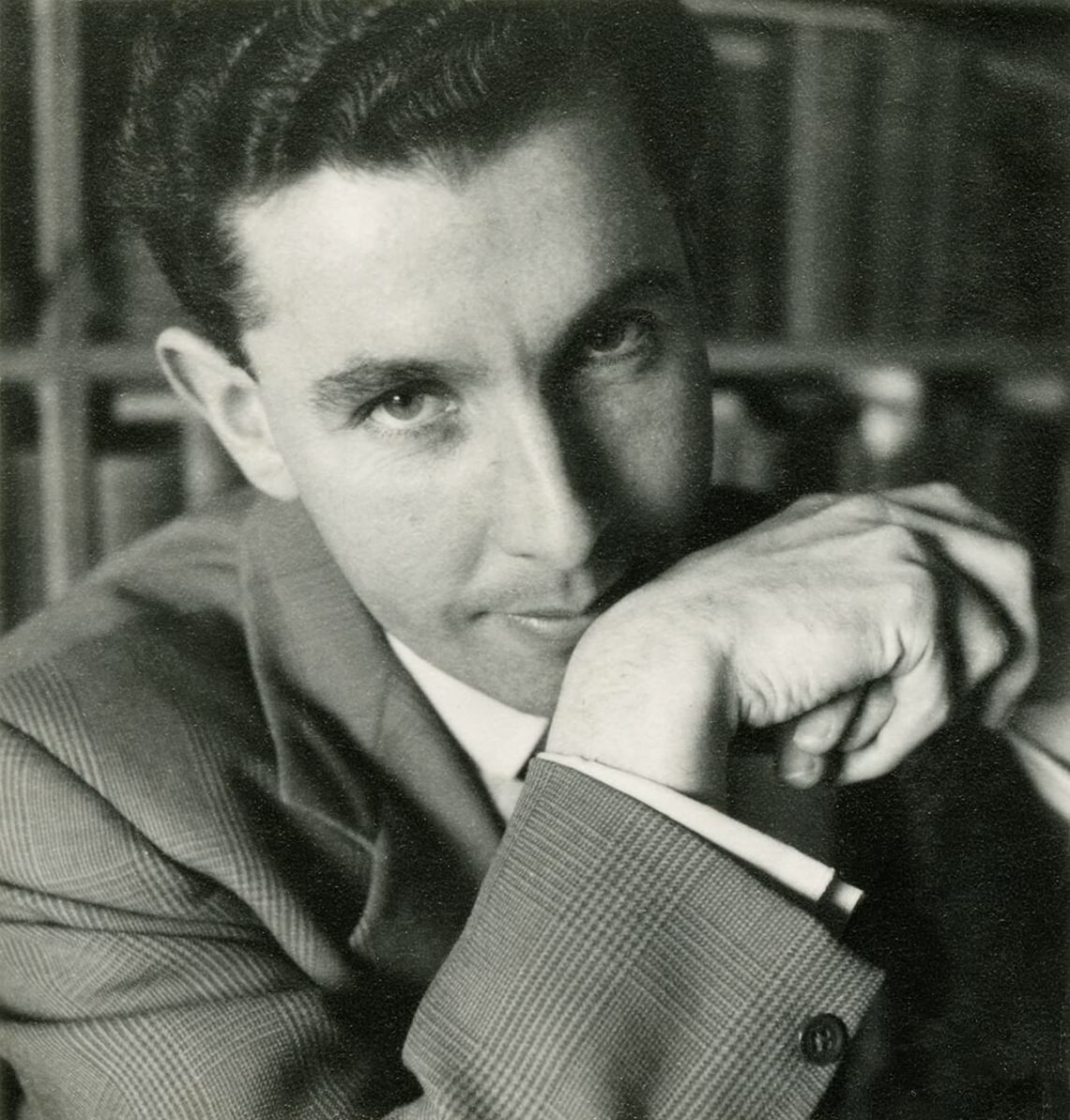

Ronald Blythe

1922-2023

Author Ronald Blythe passed away in January at the age of 100. We pay tribute here to his life, work and special connection with Britten and the Aldeburgh Festival.

I would walk from Thorpeness Bay to Orford with long rests here and there to find out if [the sea] was still speaking its mind. Once I had cleared mine of its literary lumber and its old emotions, and I had set my ear to its sound, it sang! People who write never fail to catch its voice.Ronald Blythe, The Time by The Sea

The East Anglian landscape, its people and art were all key influences in Ronald Blythe’s life and work. Born into a farming family in Acton near Lavenham, he grew up in the company of artists Sir Cedric Morris and, notably, John Nash. His love of books and reading fostered an early career as a Librarian but his vocation from an early age was to become a writer. In 1955 he found ideal surroundings in which to do this in the seaside village of Thorpeness. In April of that year, with a strong recommendation from Fidelity, Countess of Cranbrook, he accepted a position as part of the team responsible for the organisation of the Aldeburgh Festival, then in its seventh year. He became assistant to Stephen Reiss who had recently been appointed Honorary Secretary to the Festival. His first meeting with Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears was in the Festival office which at that time was situated behind the Wentworth Hotel. The office had, in his own words, fallen victim to the treacherous 1953 flood and was still ‘in a bit of a muddle.’

In the autumn of 2009, Ronald, known to nearly all as Ronnie, recorded recollections of his time in Aldeburgh at ‘Bottengoms,’ his home of many years in Wormingford, a Tudor yeoman’s house left to him by John Nash, who he cared for during the artist’s later years. In truth, Ronnie never saw himself as an administrator or manager, but his naturally friendly manner and diplomacy became a professional advantage, enabling him to liaise with locals and visitors alike. Taking the bus from Aldeburgh and walking from Walberswick, he was given the job of asking the Vicar of Blythburgh if the church could be used as a concert venue. ‘I daren’t go back [to Ben] without it all arranged,’ he recalled. His success in this area was evidence of the broad outline of duties he was asked to fulfil. This was summed up in the minutes for that first meeting in the Festival office as ‘to have full knowledge of and to understudy all activities.’ This seemingly all-encompassing brief included his having to spend a night in Aldeburgh’s Moot Hall. To satisfy the security requirements for a number of drawings by Jean-François Millet, on loan for an exhibition, someone had to remain in close proximity to where they were displayed both day and night. Ronnie’s vigil was spent in ‘the room Peter Grimes was tried in, I think!’

Ronnie also found that his Festival duties resulted in encounters with leading figures in the literary field. Meetings with Dame Edith Sitwell, who arrived by train replete with a large hamper of clothes for her Festival appearances, and E.M. Forster who accompanied Ronnie to the local bookshop in search of Quink (the bookshop owner who was hurrying to catch a train did not recognise Forster), were thrilling.

Equally important to him were the friendships he forged during his time in Aldeburgh. One of the most significant, he recalled, was with Britten’s assistant Imogen Holst. He remembered being surrounded by mounds of paper on a table in her flat as she offered him advice on editing the programme book (another of his jobs) while she attended to Britten’s manuscripts. Ronnie described her as ‘a very percipient woman.’ Once she realised where his strengths lay, she ‘made me do a lot of literary things’ and that, vitally, ‘was when I found myself’. Links made with people such as Forster, and the opportunity to write and edit further established in his own mind that writing was what he wanted to do. After three years of working for the Festival, he decided it was time to concentrate more fully on his career as an author.

Aldeburgh still played a significant part in his work. The town was the setting for his 1960 novel A Treasonable Growth, a book that showed some influence of Forster in terms of its depiction of the life lessons learnt through complicated relationships. He often met Forster, though refrained from discussing his work, while writing the book. Ronnie’s subsequent writing was a rich mix of fiction, non-fiction and editing, the last of which included editions of works by Austen, Hardy and Henry James. In 1972 Ronnie was asked to edit the Aldeburgh Anthology, a miscellany of poetry and photographs as well as writings on local history, music, art, literature, and the history of the Festival. 37 years later he was invited to contribute a Foreword to a volume entitled New Aldeburgh Anthology, which allowed him to reflect on his own time in Aldeburgh and the remarkable changes he had witnessed since.

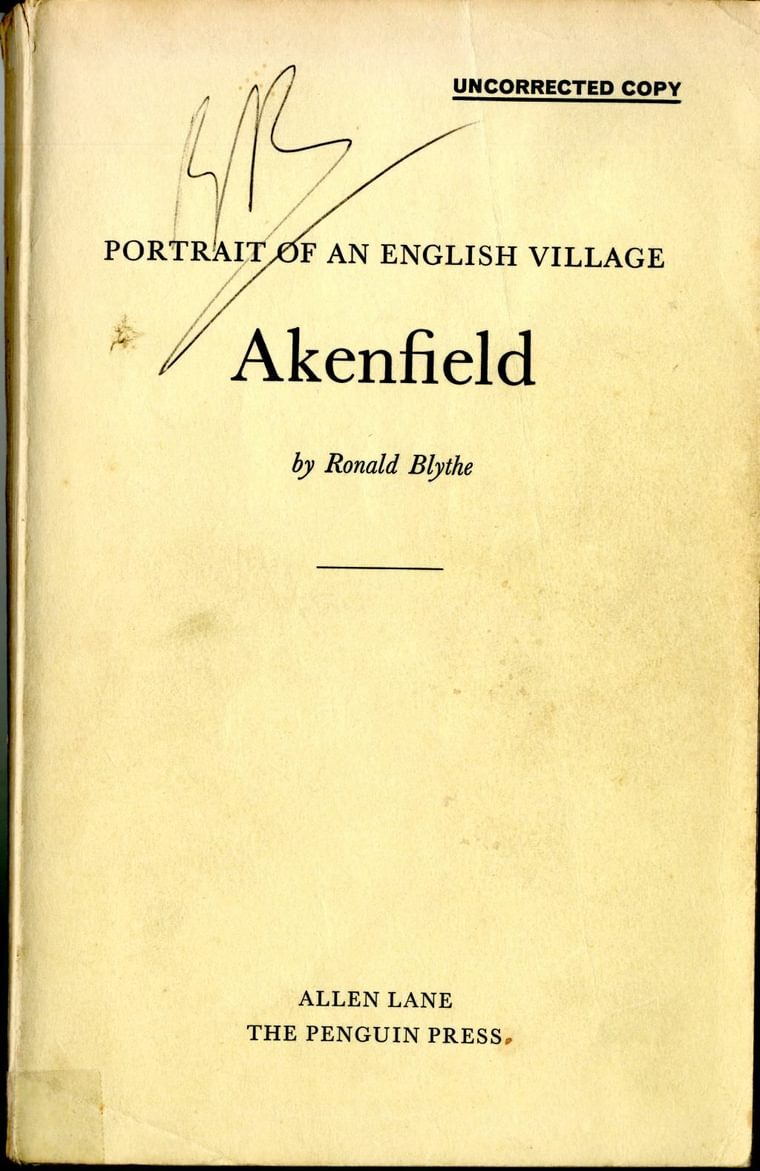

The book for which he is undoubtedly best known is Akenfield of 1969, the chronicle, or ‘portrait’ of a fictional Suffolk village. The narrative was based in part on interviews that Ronnie undertook with a number of local residents. That, as well as his innate knowledge of the land and its people, were all fundamental to the book’s realism.

A proof copy of Akenfield was sent to Britten at Ronnie’s request. The composer’s response was that he ‘was deeply impressed’ with the ‘unique picture of contemporary village life. It is amusing, disturbing and reassuring in turn’. Britten’s connection with the book would continue in ways he could not foresee. Shortly after its publication Ronnie began to collaborate with theatre director Peter Hall on adapting the book into a film. He approached Britten to ask whether he would write the score, a request the composer was happy to consider. However, the heart operation Britten had to undergo in 1973 brought any hope of his providing music for the film to an end. Happily, the Fantasia Concertante on a Theme of Corelli by Britten’s friend Michael Tippett fitted the story perfectly. It contributed to the film’s success on its premiere in 1974 and remains a key feature.

Britten’s proof copy of Akenfield

Of Akenfield Ronnie said, ‘Well, it is a book of witness, really …. Like most writers I’m an observer and a listener. One knows a lot [of what occurs] below the surface of things.’ Ronnie’s writing, faith and brilliance as a storyteller all bear testimony to a long and remarkable life.

Ronald Blythe, c.1950

Credit: Unknown photographer, from the personal collection of Ronald Blythe