Toward the end of his life Benjamin Britten urged his authorized biographer, Donald Mitchell, to “tell the truth about Peter and me.” Britten’s nearly forty-year professional partnership with Peter Pears had gained international recognition, but the story of their ‘marriage’, a term they first used to describe their relationship in the 1940s, had not been told. Following Britten’s death, Pears made initial plans to tell their story partly through the publication of their correspondence to one another. He wanted their relationship to be understood “clearly,” with their letters bearing testimony to what he called “a life of the two of us.”

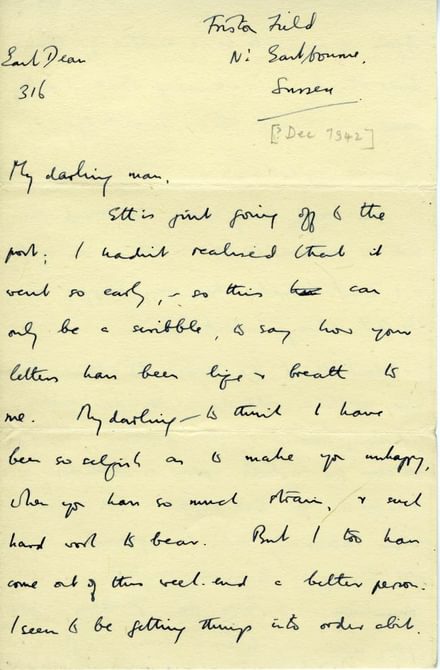

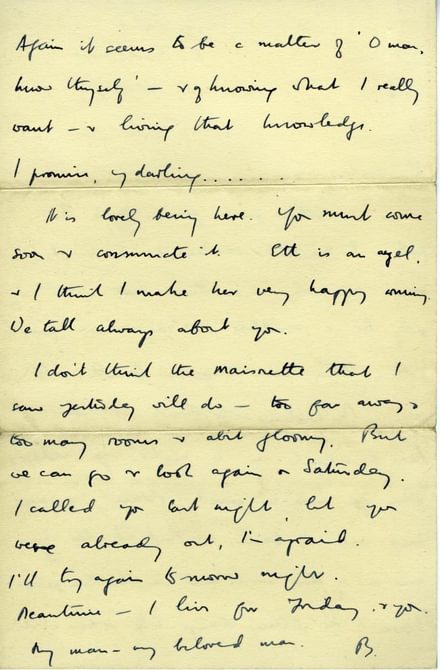

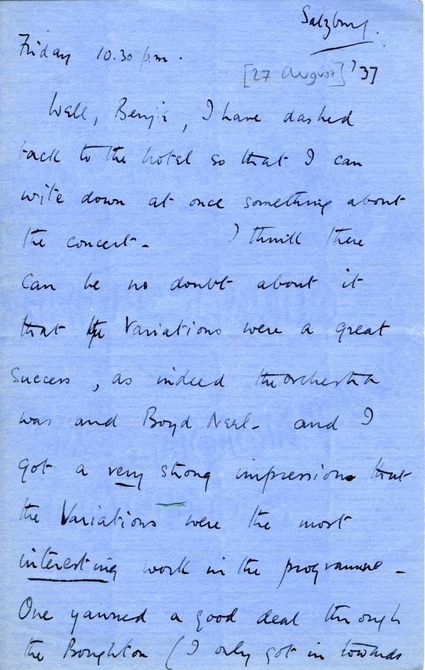

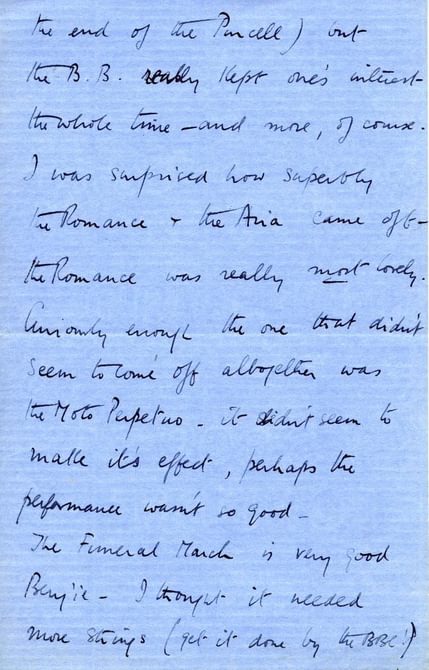

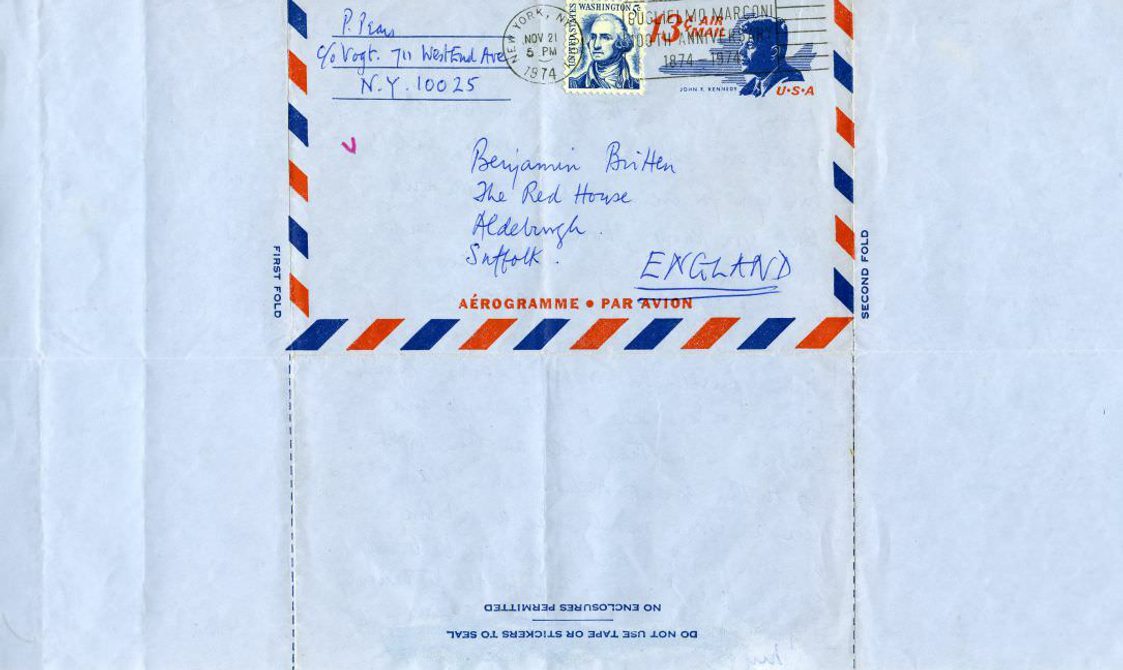

In 2016 Pears’s wish was realized and for the first time his and Britten’s letters were published in a single volume, My Beloved Man. There are 365 surviving letters in their collection, and they chronicle their relationship without inhibition – a remarkable fact when you consider that their marriage was considered illegal for all but the last nine of those forty years.

The edition contains light narrative and notes to explain context, or to describe what has happened where gaps in the correspondence occur. Taken together, these letters give a first-hand account of what comprised their daily lives. This includes their commitment to pacifism, being a professional musician, the rigours of travel, concert-giving, organizing a Festival, Pears’s thoughts on the people he worked with, insights into Britten’s frame of mind when writing operas such as Peter Grimes and Death in Venice, collecting art and literature, and establishing a home in a seaside town. More importantly, the correspondence allows Britten and Pears to relate their story truthfully, clearly, and in their own words.

Extract of Fiona Shaw's Foreword

To read these letters is to climb up a wall and peer into the secret garden of two giants. You expect to hear the roar of their success and achievements but instead you read the timpani sound of their affections. It is the terms of endearments, the ‘Honey buns’, the ‘My darlings’, that remind us we have encroached on their lives.

…

It is astonishing that these men created a totally realised domestic relationship that has remarkable contemporary immediacy during a period when it was illegal to love someone of your own sex. To me their lives seem an act of huge integrity. It shocks us into admiring the clarity of their affections.

Letter extracts

"My dearest darling,

No one has ever ever had a lovelier letter than the one which came from you today – You say things which turn my heart over with love and pride, and I love you for every single word you write. But you know, Love is blind – and what your dear eyes do not see is that it is you who have given me everything, right from the beginning, from yourself in Grand Rapids! through Grimes & Serenade & Michelangelo and Canticles – one thing after another, right up to this great Aschenbach – I am here as your mouthpiece and I live in your music – And I can never be thankful enough to you and to Fate for all the heavenly joy we have had together for 35 years. My darling, I love you – P."

Image gallery

A gallery slider

Read more

Britten & Pears

Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears were together from 1939 until Britten’s death in 1976. Yet during Britten’s lifetime, neither spoke publicly about…

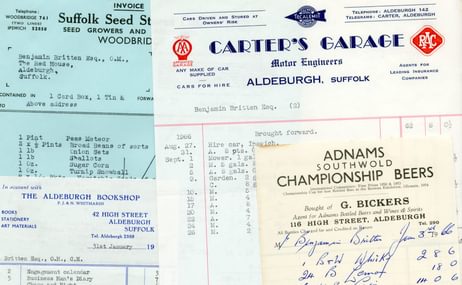

Archive Treasures: Love in the accounts

The archive at The Red House spans all aspects of Britten and Pears’ lives together – from their professional activities, the compositions and…

Archive Treasures: A Spiritual Home – Britten, Pears and The Red House

The former homes of famous people are referred to, variously, as ‘house museums’ or ‘personality houses’. They are effectively physical ‘biographies’,…