Hannah Lack tells the recently-uncovered full story of Rainer Maria Rilke’s influential letters, soon to be brought to life at the Aldeburgh Festival.

Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke was living in a dingy Left Bank apartment in 1903, amid a Belle Époque Paris in full swing. Absinthe flowed at Pigalle cabarets, high-society hostesses kept cheetahs on leads and Rachilde’s Tuesday salons attracted the city’s most unconventional minds. Rodin was working on The Thinker that year, while Rilke was working as the artist’s secretary. Not far away, Ravel was busy composing a musical landmark, his String Quartet in F major. Over on the Right Bank, Colette was finishing up her bestselling Claudine series; Paul Poiret opened his fashion house, liberating women from their petticoats in the process; and in the basement of the Petit-Palais, the first iteration of the Salon d’automne exhibited the avant-garde likes of Matisse and Bonnard. Rilke was just 28 at the time, and not yet the literary lion he would become: he’d published a handful of poetry volumes, but it was during those stimulating years in Paris that his work underwent a transformation that resulted in the compact, modernist New Poems, works scratched out in the city’s Bibliothèque nationale, in between the hundreds of letters the poet fired off to friends, lovers and the wealthy nobility who were his patrons. (He sent more than 11,000 in his 51 years.) It was in that year of 1903 that one of Rilke’s letters in particular – a reply to a teenage admirer’s hopeful missive – fuelled a correspondence that has resonated across generations for almost

a century.

A reply to a teenage admirer’s hopeful missive fuelled a correspondence that has resonated across generations for almost a century.

The story goes that in the autumn of 1902, Franz Kappus, a 19-year-old Austrian military cadet, was sitting under a chestnut tree at his military boarding school reading a collection of Rilke’s poems when the chaplain mentioned the poet had been a pupil at the same academy a decade earlier. It was not a happy time for Rilke, and the professor remembered him as ‘a slight, pale boy’. That glimmer of a connection was enough for Kappus, who was entangled in questions and crises of his own, above all the tug between his literary aspirations and a looming military career. He composed a letter to Rilke, enclosing some of his fledgling verses and soliciting the older man’s advice. He didn’t get it – at least where Kappus’ poetry was concerned. Instead, inside an envelope with a blue seal and a Paris postmark, came a weighty sheaf of pages in Rilke’s slanting, elegant handwriting that offered a wellspring of altogether more priceless and wide-ranging meditations. Over the next six years Rilke continued to post a series of candid responses to Kappus on subjects including solitude, love, death, spirituality and creativity, sometimes hastily polished off before Christmas, sometimes during the often-poorly poet’s convalescence, with a hand still aching from writing other texts. Rilke lived a peripatetic life, and they were sent from an array of addresses across Europe: his Paris lodgings, a seaside hotel in Viareggio, an artists’ community in Worpswede, an apartment near the Capitol in Rome, a castle and then a villa in Sweden.

Marilyn Monroe read them between takes on All About Eve; actor Dennis Hopper championed them as a credo of creativity; Dustin Hoffman sent the book to friends; Lady Gaga even tattooed a line on her inner left arm.

Kappus held on to these prized communications – ten in all – and in 1929, three years after Rilke’s death, he published them under the title Letters to a Young Poet. Today, the slim volume has become a pocket-sized source of wisdom, inspiration and validation for anyone struggling with life in all its messy contradictions, gathering admirers over the decades from W.H. Auden to J-Lo. Marilyn Monroe read them between takes on All About Eve; actor Dennis Hopper championed them as a credo of creativity; Dustin Hoffman sent the book to friends; Lady Gaga even tattooed a line on her inner left arm. In the 21st century, Letters … has also found a viral new life online, with sage snippets from its pages regularly pinballing across social media. (‘Let everything happen to you: beauty and terror. Just keep going. No feeling is final’ is a favourite.)

Inside an envelope with a blue seal and a Paris postmark, came a weighty sheaf of pages in Rilke’s slanting, elegant handwriting that offered a wellspring of priceless and wide-ranging meditations.

The book’s continued ability to reach far beyond literary circles might stem from the curious sensation that Rilke is speaking so directly and intimately to each of his readers alone. But it was of course one person, the would-be poet of the title, whom Rilke was addressing. When Kappus gathered the correspondence into a book, he omitted to describe his own letters in depth, focusing instead on the universal value of Rilke’s articulate words for anyone ‘engaged in growth and change, today and in the future’. Kappus’ original letters meanwhile were presumed lost or simply discarded by the poet. And so for 90 years, the conversation remained one-sided for everyone except its two interlocutors. In 2019, however, came an unexpected discovery: Kappus’ letters had been languishing in the Rilke family archive in Germany all along. With the addition of Kappus’ voice, a monologue has become a dialogue, and the mysteries and omissions of the pair’s interplay have been illuminated. The subjects Rilke chose (and chose not) to address, the ideas he brought up of his own accord, reveal the poet’s preoccupations all the more clearly. And where previously Rilke’s tone might have sounded lofty, many of his proclamations on irony, loneliness, or relationships have been shown to often be in direct answer to Kappus’ heartsick struggles.

They are arguably the most beloved letters of the 20th century, a potent source of spiritual and practical guidance to this day.

The letters stopped in 1908. Rilke would go on to embody the contradictory reputation which has seen him variously described as visionary modernist, communer with angels, houseguest of the aristocracy, self-absorbed philanderer, absent father, ‘jerk’ (at least according to poet John Berryman). For his part, Kappus did in fact become a writer – albeit without reaching Rilke’s Olympian heights – authoring newspaper columns and screenplays and working as an editor. But he remains best known for the moment he put pen to paper and elicited arguably the most beloved letters of the 20th century, a potent source of spiritual and practical guidance to this day. With the missing pieces revealed, these luminous letters continue their intergenerational dance – now a lyrical duet between mentee and mentor.

Letters to a Young Poet comes together with Ravel and Debussy’s string quartets in an inventive union of music and text at the Aldeburgh Festival on Saturday 24 June.

The full version of this article appears in the Aldeburgh Festival Book, available from the Box Office and Festival venues, 09-25 June.

Read next

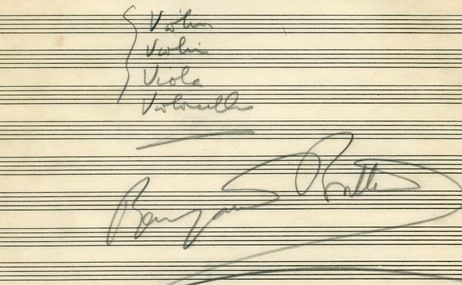

Benjamin Britten’s String Quartets

The 2023 Aldeburgh Festival offers a rare chance to hear all three of Britten’s numbered String Quartets, played across three concerts. This essay by…

Charles Byrne – the ‘Irish Giant’

Wendy Moore explores the history of Charles Byrne – the ‘Irish Giant’ – and the surgeon John Hunter

Pavel Kolesnikov's Magic Box

Camille De Rijck talks to Aldeburgh Festival featured musician Pavel Kolesnikov about his fascination with American…