The 2023 Aldeburgh Festival offers a rare chance to hear all three of Britten’s numbered String Quartets, played across three concerts. This essay by Katy Hamilton from the Aldeburgh Festival Book gives an insight into Britten’s work within this storied genre.

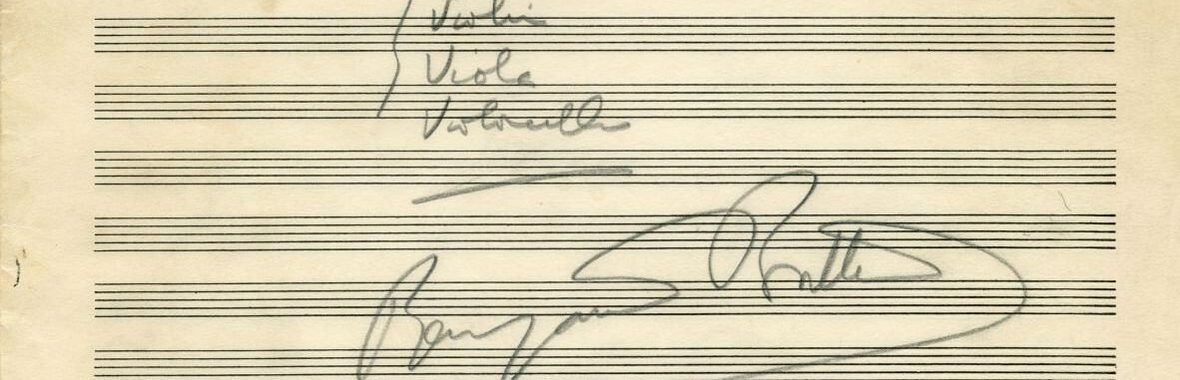

Main image: title page for Britten’s String Quartet No. 1

A conversation. An intimate discussion between friends. An argument – of themes, lines, unexpected silences. The string quartet is a genre more than 200 years old, and a fixed professional ensemble grouping only a little younger than that: but our ways of discussing what it is and what it does are overwhelmingly connected with human speech, personal interaction, and – above all – the exchange of abstract ideas. It’s curious, when you think about it. We barely talk about the musicians and their instruments at all.

Britten was himself a string player. A highly proficient violist, he almost never performed on this instrument in public. (He recorded the ‘drone’ part in Purcell’s Fantasia upon One Note in 1946, but was apparently ‘terribly nervous’ about sustaining that single C throughout the piece.) His most important teacher and mentor, Frank Bridge, had been a professional viola player, and spent more than a decade as a performer before turning his attention more fully to composition. When Britten set sail for America in 1939, Bridge presented his young protégé with his viola, ‘so that a bit of us accompanies you on your adventure.’ As Britten himself later observed, Bridge ‘taught me to think and feel through the instruments I was writing for… he thought instrumentally.’

Over the course of this year’s Aldeburgh Festival, we hear all three of Britten’s numbered string quartets. But these are far from his only pieces for the ensemble. There is, for instance, the Quartettino of 1930, evidence of a teenaged Britten dabbling in dense chromaticism as he explored the relatively recent new soundworlds of Arnold Schoenberg and Alban Berg. That Britten was later to fail not only to persuade the authorities at the Royal College of Music to allow him to study with Berg, but also to purchase a score of Schoenberg’s Pierrot lunaire for the college library, speaks of the level of general mistrust in that august institution for Continental musical developments. Although free atonality was not an approach Britten chose to pursue, he continued to write for the medium in unpublished and unfinished works as a student. It was a known genre, one with a history, and thus a natural ensemble type for a precocious young composer to explore.

This magic comes only with the sounding of the music… Benjamin Britten

The Britten of the Quartettino and other early chamber pieces was responding to a tradition that privileged a certain combination of instruments. The Britten of the First Quartet was over a decade older, considerably more experienced in his craft, and enjoying the hot Californian summer of 1941. What did it mean for this 27-year-old composer to be turning his hand to a genre that reached back through the music of Bartók and Brahms to Beethoven, Mozart and Haydn? For a musician whose catalogue otherwise lacks the ‘standards’ – abstract symphonies, tone poems, piano sonatas – why did the quartet remain of such interest?

One answer might be to do with precisely that level of abstraction that tends to creep into discussions of the quartet more generally: in other words, form. The First Quartet is a four-movement work in a traditional pattern of fasts and slows, but with surprises along the way. Most strikingly, the first movement fools us into thinking that it has a slow introduction, when in fact the opening bars are a crucial structural component within a sonata form structure. For those attentive to Britten’s knitting together of themes and motives, there is much to admire here. For those of us without such analytical interests, it is the way in which he conceives of the quartet – to put it bluntly, the noise it makes – that is so completely enchanting. That high, hovering stillness of the opening; the scrubby energy of the faster music that follows; the wry pizzicati, interspersed with sudden bowed ducks and dives from each player, that characterize the second movement; the extraordinary warmth and tenderness of the Andante’s chorale-like textures. Bridge had taught him well – this is music that thinks instrumentally, as much as thematically, and Britten’s satisfaction at the Quartet’s positive reception is palpable in his letters home. ‘I’m to be presented with a gold medal at the Library of Congress in Washington,’ he reported to his brother Robert in August 1941. This work had been a commission from Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge, a rich and energetic supporter of the arts, and she now proposed awarding him the Coolidge Medal for services to chamber music. ‘Getting quite distinguished arnt I?’, [sic]Britten observed to Robert. ‘But it doesn’t mean any money, unless I sell the medal, which wouldn’t be quite quite. Still the old girl has just bought a string quartet off me for quite a sum, which will keep the wolf away for a bit, so I can’t complain.’

A rehearsal by the Amadeus String Quartetfor the premiere of Britten’s Quartet No.3, Snape Maltings Concert Hall, 19 December 1976. From left: Peter Pears, Colin Matthews, Imogen Holst and Donald Mitchell Photo: Nigel Luckhurst © Britten Pears Arts

Like the First Quartet, the Second was a commission, this time to commemorate the 250th anniversary of the death of Henry Purcell. Britten had been thinking for some time about writing a new piece for these forces, and this project provided the perfect opportunity to think anew about what a quartet was and could become. Purcell’s own Fantasias and other pieces for four string instruments are clearly referenced in the Quartet’s ice-clear textures and imitative voices. Four movements are reduced to three, the finale a substantial Chacony – a Purcellian form if ever there was one, from the circling basslines of his instrumental pieces to his most famous aria, ‘When I am laid in earth’, from Dido and Aeneas. Britten’s Chacony is of a slightly different order, varying not only the surrounding context of the repeating line, but its pitches and rhythms too. As the composer’s friend Hans Keller later observed, ‘The idea of ending with a passacaglia (or freer-type variations, or an old dance form) has its counterparts in the present and its roots in the past.’

Let’s place Keller centre-stage for a moment, as one of the most important cultural commentators of his generation. Austrian-born and a British resident from 1938, Keller was a fine violinist, critic, biographer, teacher and, perhaps most memorably, BBC speaker and programmer. He loved football, interviewed Pink Floyd, and wrote extensively about film music. He also had a highly sophisticated understanding of music analysis, and it is clear that he and Britten had many lengthy conversations about the formal construction of – amongst other things – string quartets. Those keen to look ‘under the bonnet’ of Britten’s Second Quartet should seek out Keller’s pithy little article of 1947. It’s all there, movement by movement, in a mere six pages.

Keller’s preoccupation with form is hardly unique among writers on music: as I mentioned at the beginning, this is precisely how quartets are usually presented to us. But the very fact that Keller and Britten were friends, that they belonged to the same generation, and that Keller’s analytical writing belongs to the period from the 1940s to the 1980s, should remind us that these kinds of discussions, as well as Britten’s quartets themselves, are historical artefacts. Fifty years after Britten’s death, and almost 40 after Keller’s, we have other ways of talking about music, other ways of noticing the details of what we’re listening to. That’s not to say that those incisive analytical essays don’t still have things to teach us. But if we’re not out to spot the quirks of Britten’s sonata form structures, what might we hear instead? How else might we talk about this music?

To return to the Second Quartet, we might think about some of those ‘updated’ Purcellian features: staggered entries between players, repeated motives, extremes of range with players sliding between notes. There is the question of players, since Britten knew and greatly admired the leader of the ensemble which premiered the piece in 1945, Olive Zorian. The Zorian Quartet recorded the Quartet the following year, the remaining space on the record taken up with Purcell’s Fantasia and Britten’s appearance as the viola player with just one note to play. And this in turn speaks of the programming of the Quartet, since it was written to sit alongside the music of Purcell, to contrast and emphasize the music of that far earlier composer who had died on 21 November 1659, exactly one day and 254 years before Britten was born.

Thirty years separate Britten’s Second Quartet from his Third – three decades in which he had experienced international fame, written a host of brilliant works large and small, enjoyed extensive travel and, in the end, suffered serious ill health. This time there was no commission, no anniversary, and no gold medal. But there was a conversation with Keller, many years earlier, that had evidently stuck in his mind: a discussion about sonata form and constructive principles. And there were the very real physical limitations imposed by Britten’s frailty which made man-handling a full orchestral score too difficult. ‘I wrote him a pseudo-jocular note suggesting that this was the time for four staves,’ Keller recalled, ‘… the ideal time for a string quartet, for our musical culture’s private, personal work par excellence.’

Lo and behold, Britten did indeed write a string quartet, and dedicated it to Keller. He also included in its fifth and final movement a series of quotations from his recently completed final opera, Death in Venice. Self-quotation is far from commonplace in Britten’s music: clearly Keller’s description of the quartet as private and personal was on the money. And what’s more, the quotations in question are all taken from the music of Gustav von Aschenbach, celebrated novelist and central character of the opera.

Once again, Keller provides a detailed analytical commentary of the Third Quartet for those who desire it. Yet this time even he is also beguiled by the extraordinary deftness with which Britten handles the sonic potential of his ensemble. The first movement plays with ‘Duets’, plucked and bowed; the briskly edgy ‘Ostinato’ and ‘Burlesque’ seem reminiscent of Bartók in their energetic, sometimes angular shapes. The third movement ‘Solo’ has a feeling of emptying out, only the heart-rending bare bones remaining of a once richer texture. Of the Death in Venice quotations in the Passacaglia finale, Keller says nothing. Later analysts have suggested that they may suggest a final redemption of Aschenbach beyond the confines of the opera. Perhaps since Britten himself chose not to mark them in the score (the last movement is simply subtitled ‘La Serenissima’, and indeed Britten sketched it on his final visit to Venice in late 1975), Keller too draws a veil here. Of the piece’s final bars, its lack of resolution, Keller recalled that on attempting to explain this in a lecture here at Snape, he ‘ventured that the only possible verbal translation of these last, unfinal notes was, “This is not the end”. Whereupon Donald Mitchell, the composer’s authorized biographer, recounted that in reply to the question what this end meant, Britten had said, “I’m not dead yet”.’

The Third Quartet was, indeed, not quite Britten’s final composition, and a few short pieces and arrangements followed before the composer’s death on 4 December 1976. He did not live to hear the public premiere, given on

19 December by the Amadeus Quartet, with whom he had rehearsed the work in the Red House library several months earlier. But even before this four-player workshopping, Britten had heard his Quartet in a piano duet reduction, performed for him by Colin and David Matthews in mid-December 1975. Stripped of its string sonorities, this would have been a rather different auditory experience – and one might think that it would provide the perfect opportunity to talk themes, musical arguments, and abstractions. But in the end, that was not what interested Britten the most, as David Matthews recorded in his diary. ‘After we had finished there was a silence and then Ben said, in a small voice: Do you think it’s any good? We assured him that it was.’

The full version of this article appears in the Aldeburgh Festival Book, available from the Box Office and Festival venues, 09-25 June.

Hear all Britten’s String Quartets at the 2023 Aldeburgh Festival

Snape Sessions: Robert Owens

Join us for a night of deep grooves and soulful energy as we welcome house music legend Robert Owens to the Britten Studio.

Britten Studio, Hoffmann Building, Snape Maltings

|

More info

Free event:

Mini Music Makers in the Jerwood Kiln Studio

Mini Music Makers is being taken over and moved to The Jerwood Kiln Studio at Snape Maltings for a joyful one-off session led by residency artists Hugh Nankivell and Wils Wilson.

Jerwood Kiln Studio, Snape Maltings

|

More info

Legacy Coffee Morning

|

More info