Gordon Crosse, 1 December 1937 – 21 November 2021

Composer Gordon Crosse’s later appearances at the Aldeburgh Festival were marked by a quietly jovial presence, one which belied the fierce imagination and engaging drama that could often be found in his music.

Born in Bury, Lancashire in 1937, he completed his primary and secondary education in the North before taking a place at St Edmund Hall, Oxford where he achieved a first in Music in 1961. Further music study took him to the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia in Rome, primarily to focus on the history and practice of early music, a fascination that is reflected in some of his own composition. On his return to the UK in 1963 he took up a number of academic postings, as Haywood Fellow in Music at the University of Birmingham, Fellow in Music at the University of Essex and as Composer-in-Residence at King’s College, Cambridge. He also undertook periods of teaching in California and at the Royal Academy of Music in London.

He gained Britten’s attention after a choral work Meet My Folks! was programmed at the 1964 Aldeburgh Festival. This setting of verse by Ted Hughes, with whom he would work again, is described as ‘A Theme and Relations’ and was written specifically for children’s choir, speaker, percussion band and instrumental ensemble. As Donald Mitchell observed in his programme note, the concert in which it was performed continued a tradition of music for young people pioneered by Holst and Vaughan Williams, carried on by Britten and ‘taken up by a host of younger contemporaries among English composers. Four of them—Malcolm Williamson, Alexander Goehr, Thea Musgrave and Gordon Crosse—are represented in our programme, Mr Crosse by a new work written for the occasion.’

This was the first of several premieres that took place at Aldeburgh. The following year Gordon’s setting of the anthem O Blessèd Lord was given its first performance by the Purcell Singers and cellist Keith Harvey during a late-night programme at the Parish Church.

He welcomed the opportunity to find a niche in the Festival, enjoying its (at the time) less than two decade old tradition of blending old and new music. And he developed a love of the environment. In fact, Britten’s music and the landscape that inspired it were two significant factors in Gordon’s decision to settle in Suffolk in 1968, effectively making his home here for the remainder of his life. His decision also brought him into closer contact with Britten and, as a consequence, the older composer’s influence became noteworthy. This is particularly evident in the second of two one-act operas that premiered at the 1969 Aldeburgh Festival. The Grace of Todd (with libretto by David Rudkin) was styled as a ‘Comedy in Three Scenes’ although its content—the humiliation suffered by day-dreamer Private Todd during military training—would have struck a resounding chord with pacifist Britten. Gordon recalled how Britten took time to review the score with him in The Red House garden, offering constructive criticism and adding practical ideas over points of orchestration, which he believed would improve the piece. ‘Your friendly interest in my operas has been more encouraging to me than I can possibly say,’ he wrote to Britten immediately after the first performance The Grace of Todd. His correspondence tells of a lengthy, rewarding friendship built out of mutual interests, especially in chamber opera. The potential scope for works such as Todd to offer a powerful message probably stands behind Gordon’s lasting admiration for the moving Curlew River—the ‘piece which influenced me [more] than any other’.

Similarly, something of the spirit of Noye’s Fludde was infused into The Wheel of the World, a mixture of drama and music that was first performed at the 1972 Festival. Based on Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales it showed the hallmarks of community music-making for it was devised for the combined forces of the Lowestoft Theatre Centre, Lowestoft Youth Orchestra and music staff who performed the piece at Orford Church. Like the Fludde, which was premiered in Orford 14 years earlier, it provided the first opportunity for many young people to experience the joy of acting or singing in front of an audience.

Other music dramas (some with rather unconventional scenarios) incorporating the talents of young performers followed. Potter Thompson, a story about the mysterious nature of heroism (which employs handmade instruments known as a ‘noise orchestra’) and the Nativity opera Holly from the Bongs were written in collaboration with his good friend, renowned author Alan Garner. He worked again with text by Ted Hughes on The Demon of Adachigahara, another piece for young singers. Based on a Japanese folk tale, the cantata also calls for an intriguing mix of narrator, optional mime and orchestra.

Literature inspired various other works. Gordon’s second violin concerto (1969) was based around his reading of Nabokov’s verse novel Pale Fire, whereas his pastoral concertante for flute and double string septet ‘Thel’, written for Richard Adeney (another Aldeburgh premiere, 1978), has the writings of William Blake at its heart. There were also notable literary connections with the work he produced for drama. Incidental music for productions of Peer Gynt, Philoctetes and Moby Dick number among his pieces for stage and his score for the 1983 Granada adaptation of King Lear, featuring Laurence Olivier, brought recognition in the field of television.

This is a reminder of the reputation Gordon gained beyond Aldeburgh, something that was reflected in the award of major prizes such as the Vaughan Williams Composer of the Year award given to him in 1966, and the Cobbett Medal received a decade later. And yet Suffolk was seldom far from his imagination. His ballet Young Apollo was based around Britten’s fanfare for piano and orchestra of 1939. The kernel of the idea was extended into a 30 minute score and first performed at Covent Garden in 1984.

The home he shared with his wife Elizabeth also owes something to the music that came from Suffolk, for it was during one of the festivals that he first met her, on the steps of Orford Church. They lived at Wenhaston, where they raised their two sons, until Elizabeth’s death in 2011. His fourth symphony (2015) is dedicated to her memory.

Although he took an extended break from composition in the 1990s he was lured back to writing again post millennium. Always seeking out new sources from which to draw music, he looked to the Carmina Gadelica, an early twentieth-century compilation of ancient Scots prayers, poems, charms and tales, for what would be his final Aldeburgh commission. A simple prayer of thanksgiving for creation Hey the Gift was written for the Britten-Pears Chamber Choir and received its premiere at the 2010 Festival.

This final work for Aldeburgh could easily allude to his own gratitude for the music Suffolk had drawn from him during a long, fruitful career. In two recorded oral history interviews, one with Andrew Plant in 2002 and the second with Stephen Lock in 2009, Gordon spoke about the influence Britten had on him. ‘One should be proud of being within that tradition,’ he commented when comparisons were drawn between his and Britten’s music. ‘I don’t think we should be ashamed of being under the shadow of somebody’. He believed the key to gaining ground as a composer was to learn from a great tradition, but also to establish your own voice. Gordon Crosse’s voice will continue to speak to us for some time to come.

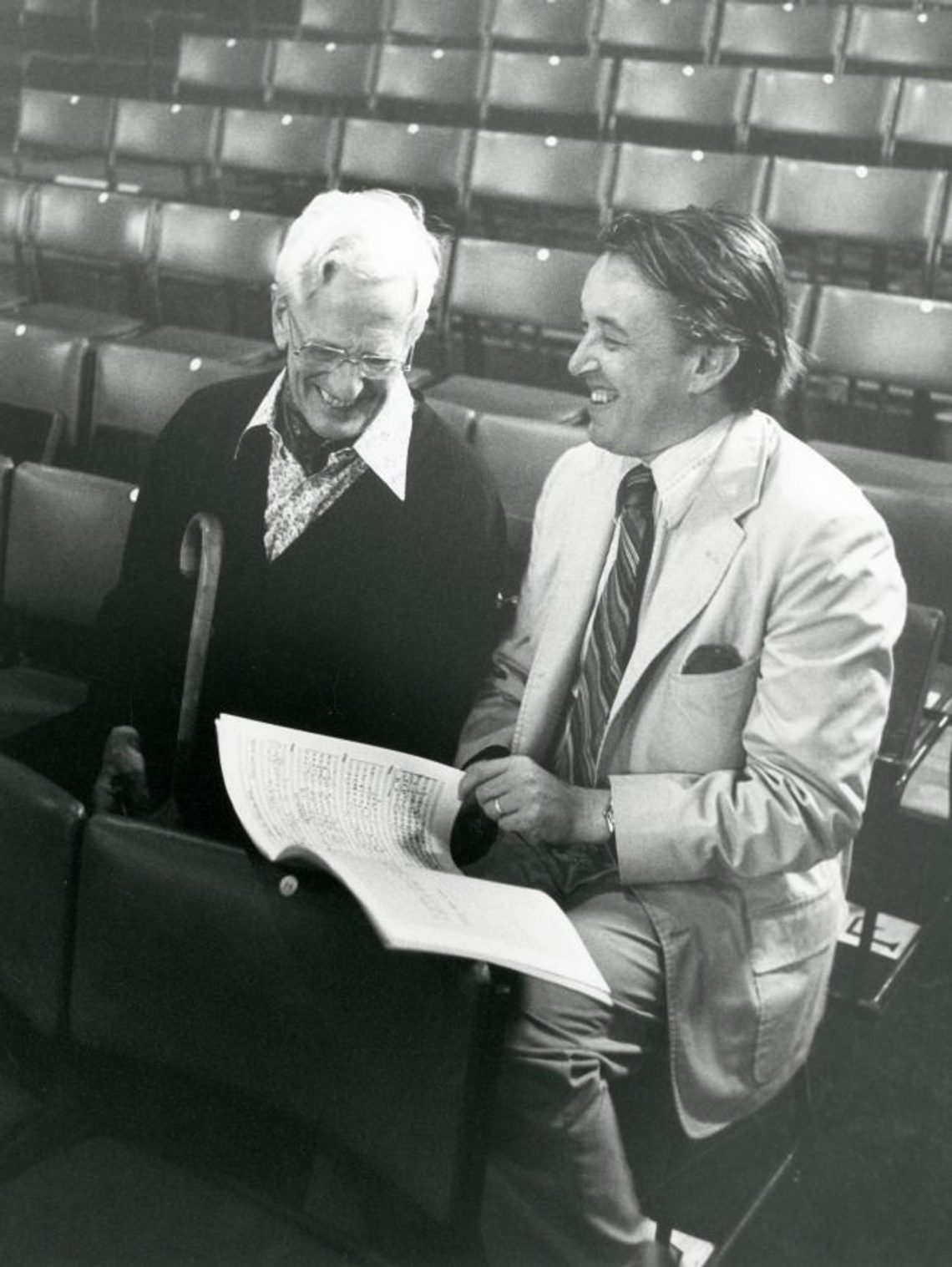

Peter Pears and Gordon Crosse at a rehearsal of Crosse’s Elegy and Scherzo, performed by Chetham's Chamber Orchestra, Jubilee Hall, Aldeburgh, June 1981.