Wendy Moore explores the history of Charles Byrne – the ‘Irish Giant’ – and the surgeon John Hunter

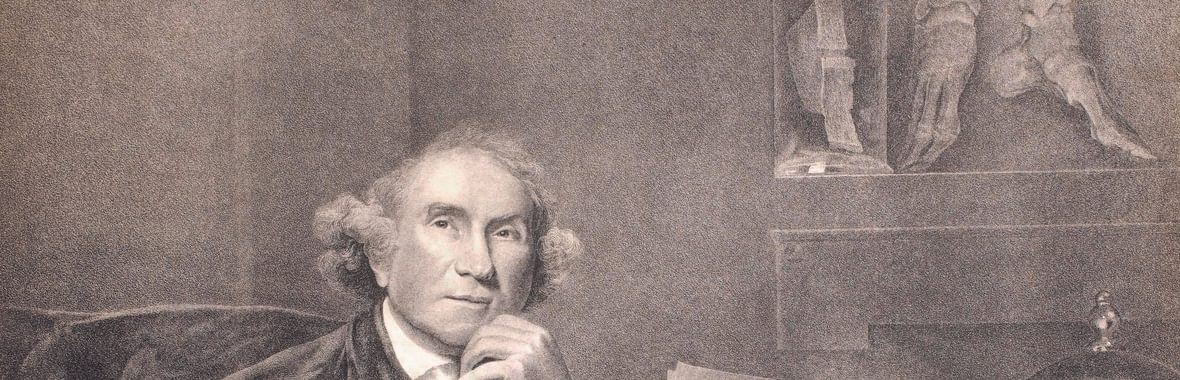

Main image: Print of John Hunter (1728–1793), after Joshua Reynolds’ painting of 1789. Charles Byrne’s feet are displayed top right Science Museum, London. (CC BY 4.0)

Sarah Angliss’ new opera Giant focuses on the fate of Charles Byrne (1761–1783), the self-named ‘Irish Giant’, but it also puts John Hunter, the surgeon obsessed with obtaining Byrne’s body, under the microscope.

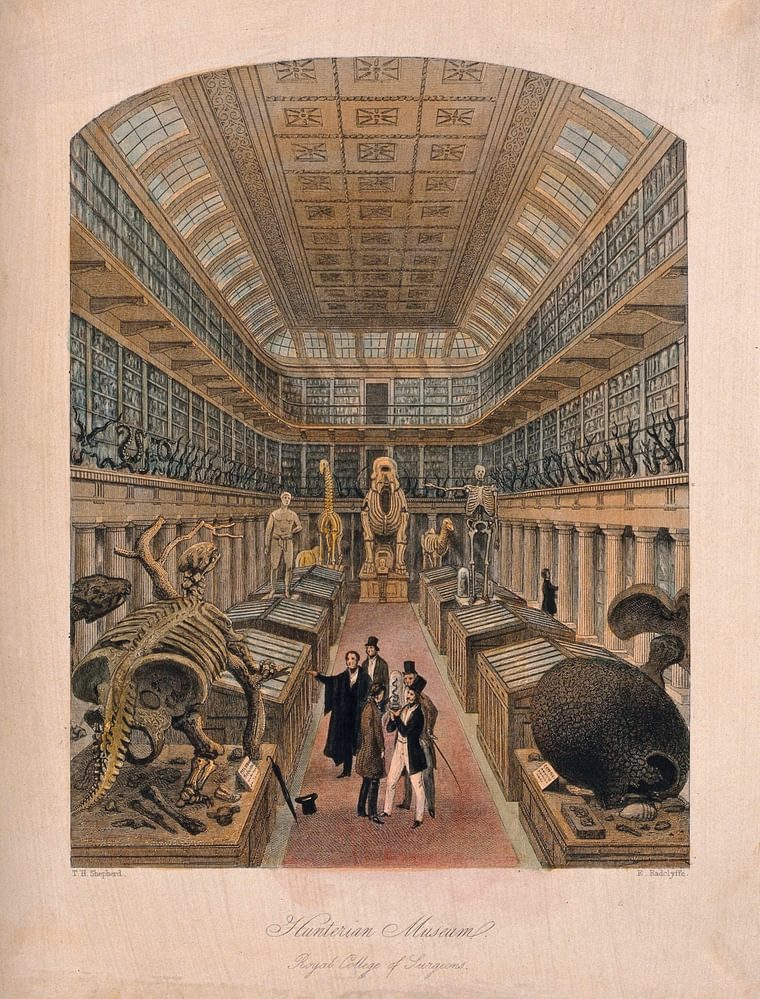

In 1788 the renowned Scottish anatomist John Hunter opened his museum in London’s Leicester Square to public view for the first time. Many of the invited guests had heard rumours about the contents of the controversial doctor’s collection which he had spent a lifetime creating. The reality was even more surprising than any could have imagined.

As they entered the vast two-storeyed room, visitors gasped at the sight of a stuffed giraffe, the first such animal seen within British shores, and stared in wonder at the bones of whales, camels and elephants suspended from the ceiling. They marvelled at the intricate parts of humans and animals expertly dissected and preserved in jars. They included rare creatures, such as a Surinam toad carrying its young in pockets on its back, and anatomical curiosities like the five shrivelled bodies of stillborn quins. But most spectacular of all – to the guests wandering the crowded room – was the museum’s centrepiece: the magnificent skeleton of Charles Byrne, better known as the ‘Irish Giant’, as he towered above their heads.

Ever since Byrne’s death in London five years previously, stories had circulated about the whereabouts of his body. Now his fate had finally been revealed. Despite Byrne’s express wishes, he had ended up in precisely the place he had most dreaded – on public display as a human freak in the centre of Hunter’s museum. In truth, even as the visitors gawped at the sight of Byrne’s 7’ 7” tall skeleton, few were surprised to see it. For almost everyone in London knew that Hunter had been determined to obtain the giant’s body from the moment he had first clapped eyes on him.

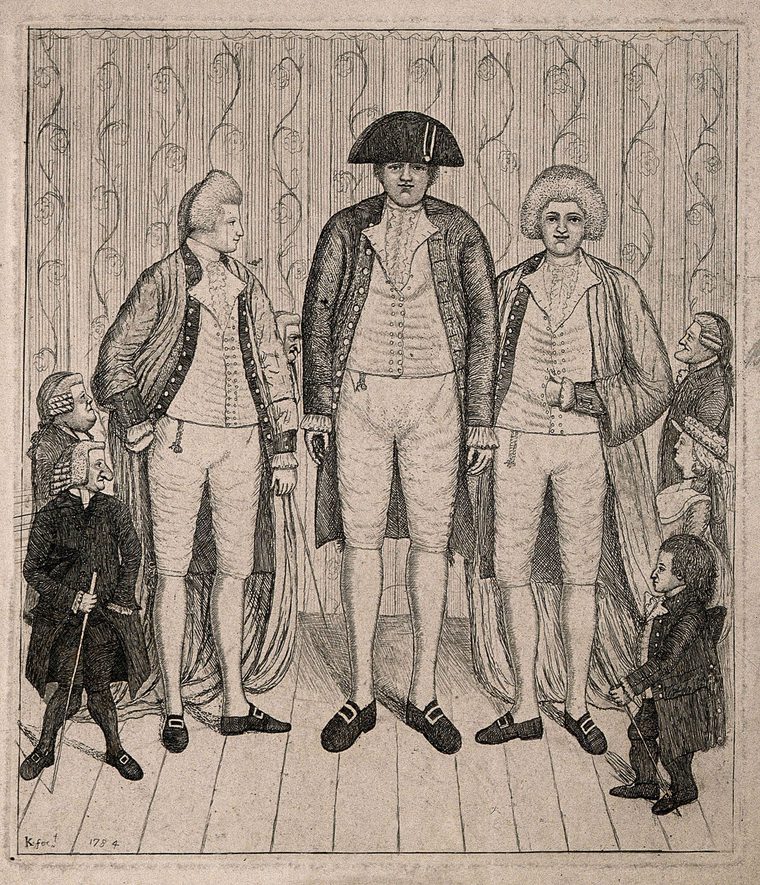

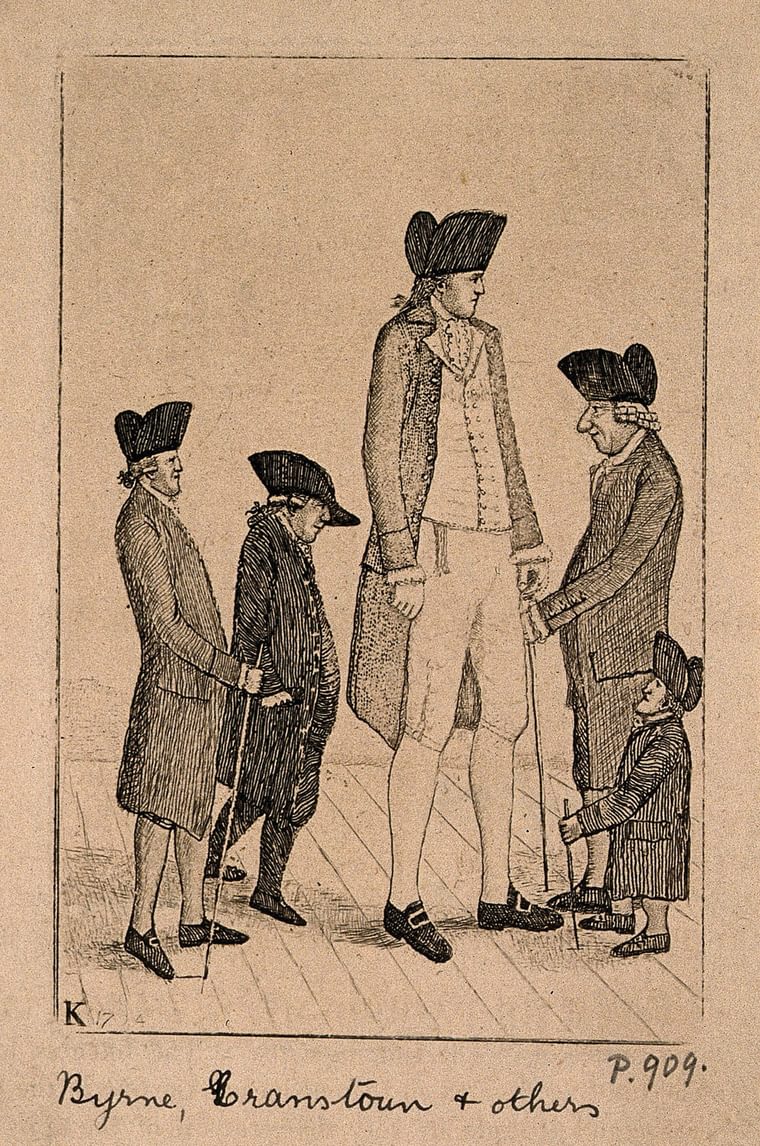

Three giants, the tallest identified as Charles Byrne and the others as twins, and six spectators including an unidentified lady and a man of restricted growth. Etching by J. Kay, 1784 Wellcome Collection

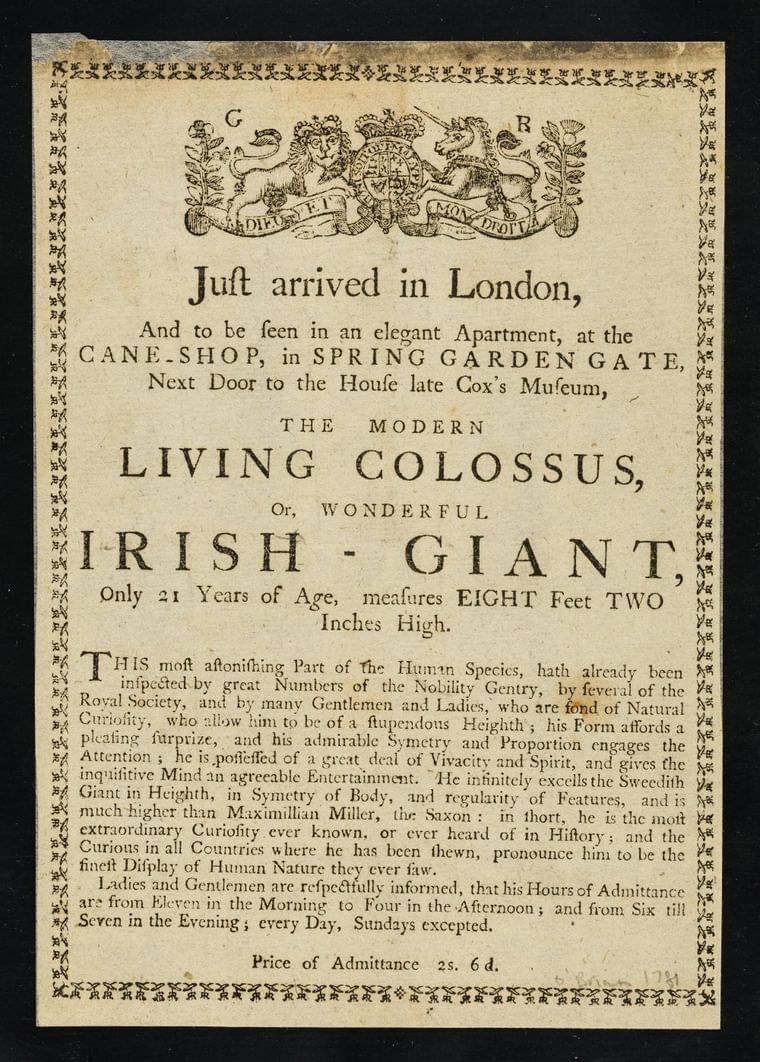

Byrne had arrived in London in 1782 after travelling from his homeland in Ireland to Scotland then northern England. Born in Littlebridge, a hamlet on the border of County Derry and County Tyrone in 1761, he had quickly outgrown his playmates. News of the tall lad spread rapidly, generating myths such as the story that he owed his unusual height to his parents conceiving him on top of a haystack. The stories attracted the attentions of a local entrepreneur, Joe Vance, who convinced the boy’s parents to let him exhibit the youth as a curiosity at country fairs. As crowds flocked to see the shows, Vance decided to take Byrne to Britain to maximize his investment.

When Byrne arrived in Edinburgh, newspapers reported that he was so tall he could light his pipe from one of the lamps on the city’s North Bridge. Vance played up the hyperbole, exaggerating Byrne’s height to 8’ 2” and proclaiming him the ‘tallest man in the world’. When the pair reached London, Byrne became the talk of the town. Audiences queued to see the gentle giant with his stooped shoulders and placid manners who dressed in a fashionable frockcoat, waistcoat and knee breeches with silk stockings, frilled cuffs and collar. Byrne met the King and Queen and was represented on stage in a pantomime named Harlequin Teague or the Giant’s Causeway. At one extraordinary meeting, he was even introduced to Count Joseph Boruwlaski, the self-styled ‘Polish Dwarf’. The pair shook hands in a scene reminiscent of Gulliver’s Travels. But nobody was more captivated by Byrne and his stupendous size than John Hunter.

Feared and revered in equal measure, Hunter was the most famous surgeon of his day. Like Byrne he had come from relatively humble beginnings. He was born in 1728, the tenth child in a farming family in East Kilbride near Glasgow. He had little formal schooling, learned to read very late and spent most of his youth collecting birds’ eggs and dissecting small mammals, driven by an insatiable curiosity to understand the natural world. At 20, he joined his older brother William at the anatomy school William had set up in Covent Garden. There, for the next 12 years, Hunter explored the human body, dissecting by his own estimate some 1,000 corpses stolen from graves. By the time he left his brother’s school, he knew the human anatomy better than any of his contemporaries.

By 1782, when Charles Byrne arrived in town, Hunter had gained a sizeable private practice and a formidable reputation. He treated the celebrities of his day, including the prime minister William Pitt and the economist Adam Smith, but also operated on his poorest patients for free as a surgeon at St George’s Hospital. Hunter was also a brilliant naturalist, who kept wild animals at his farm in Earl’s Court, and an adored teacher who taught some 1,000 students his pioneering ideas on scientific surgery.

The Royal College of Surgeons, Lincoln’s Inn Fields, London: the interior of the Hunterian Museum. Coloured engraving by E. Radclyffe after T.H. Shepherd Wellcome Collection

But as well as earning fame for his scientific skills, Hunter had obtained notoriety for his nefarious deeds. He was well-known as a favourite customer of the body-snatchers who delivered fresh corpses from paupers’ graves to the back door of his house every night throughout the winter when the dissection classes ran. Hunter’s patients knew, therefore, that his surgical talents might save their lives but if he failed their bodies could very well end up on his dissecting table and their remains in his museum.

Not surprisingly, popular feeling against anatomists like Hunter ran high. For most people the idea of being dissected after death provoked horror and disgust. The Murder Act of 1752 ruled that murderers should be publicly dissected after hanging as punishment for their crimes. Being dissected, and possibly placed on display in an anatomy museum, was therefore regarded as a fate reserved for the most heinous criminals. The artist William Hogarth graphically depicted the common terror of dissection in his cartoon The Reward of Cruelty showing a grinning anatomist carving up a hanged youth on a dissecting table. The playwright John Gay evoked the same theme in The Beggar’s Opera when one character laments that a fellow gang member has been hanged and his body displayed ‘among the otamys’ – anatomies – at Surgeon’s Hall. The line survives in Britten’s 1948 realization. Another cartoon, published in 1782, lampooned the commonly-held belief that anyone who was dissected could not be resurrected whole on Judgement Day in a scene at the anatomy school run by Hunter’s brother William.

In reality anatomists had little choice but to rely on stolen bodies. In Georgian times it was extremely rare for people to donate their bodies for dissection to aid medical research – although John Hunter encouraged people to consent to post mortems for themselves and their loved ones. A handful of bodies of hanged criminals were granted to the Royal College of Physicians and the Company of Surgeons for dissection every year. But there was no

legal source of bodies for private anatomists until the 1832 Anatomy Act. They had no alternative, therefore, but to rely on the ‘Resurrectionists’ to supply them with stolen corpses in order to research the human body and teach future surgeons.

By the 1780s the trade in stolen bodies was big business but the authorities turned a blind eye to the practice. The government knew the country needed skilled surgeons for the army and navy and most of society appreciated the need for surgeons to practise their art on the dead before they turned to the living.

Leaflet advertising appearances by Charles Byrne, the Irish Giant. 1781? Wellcome Collection

Hunter dissected more stolen bodies than any other anatomist in Britain and was well known for paying high prices for anything unusual. In his collection he boasted a calf with two heads and a pig with two bodies. He took a special interest in human curiosities too; he befriended Boruwlaski and persuaded him to pose for a portrait. Hunter’s obsession with human abnormalities was not just idle fascination. Ever since he was a boy Hunter had dedicated his life to puzzling out the origins of life on earth and how different species had developed. Hunter realized that inherited deviations in plants, animals and humans were a vital clue to how species had changed over time – effectively evolved. He believed Byrne’s body might provide a piece of this puzzle.

After a year in London, Byrne’s health started to deteriorate. Falling income from his shows forced him to move to cheaper rooms in Cockspur Street near Charing Cross and he turned to drink, most probably to ease the headaches and aching joints which plagued him. His condition, acromegaly – caused by a benign growth on the pituitary gland – was untreatable at the time. Hunter’s expert eye told him that Byrne did not have long to live and he decided to make his move.

At first Hunter attempted a direct approach. He sought out Byrne, either personally or through an intermediary, and offered him a large sum if he would let Hunter dissect his body after death. Byrne, however, was horrified and bluntly refused. So Hunter turned to subterfuge. He recruited a man named John Howison, probably a professional body-snatcher, to stalk Byrne day and night like a shark circling its prey. Howison dutifully followed his quarry as he stumbled from tavern to tavern and even moved into rooms a few doors from Byrne’s apartment.

By May 1783 Byrne knew he was dying. Well aware that Hunter, and other anatomists, were eagerly awaiting his demise, he gathered his friends and made them promise that after his death they would seal his body in a lead coffin and bury him at sea. He died on 1 June 1783. True to their word his friends transported him in a lead coffin to the Kent coast and there they plunged the casket into the English channel. But whatever ended up at the bottom of the sea it was not Byrne’s body. Hunter, it later transpired, had bribed the undertaker who accompanied Byrne’s friends; they too may also have been involved in the plot. When they broke their journey at a tavern along the way he switched Byrne’s body for paving stones and drove the body back to London where Hunter was waiting to receive it. There Hunter boiled the body in a copper vat and pieced together the skeleton.

Charles Byrne John Kay 1794 Wellcome Collection

For five years Hunter kept his trophy a secret although he provided a hint of his actions when he told his friend, the naturalist Joseph Banks, ‘I lately got a tall man’. It was only when he opened his museum to public view in 1788 that the fate of Charles Byrne was finally confirmed. Byrne’s skeleton remained on display for more than 200 years until 2017 when the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons closed for refurbishment.

In the meantime the museum’s custodianship of Byrne’s skeleton has caused widespread controversy. Various voices – mine included – have called for Byrne’s body to be buried at sea, as he requested, while others have argued that he should be returned to his native Ireland and buried there. But the museum’s trustees have long insisted that his body should be retained for medical research. The cause of Byrne’s condition was first identified as a pituitary tumour by the American surgeon Harvey Cushing in 1909; in the early 21st century researchers extracted DNA from a tooth in order to pinpoint the genetic mutation responsible.

Controversy has been heightened as museums worldwide have re-evaluated their collections in the light of ethical concerns over human rights, with several agreeing to return human remains and other items that were obtained by illicit means to their original communities. Finally, the Hunterian Museum’s trustees have announced that Byrne’s body will no longer be displayed in the reopened museum but will instead be kept in storage for potential future research. In a statement the trustees said they ‘recognize the sensitivities and the differing views surrounding the display and retention of Charles Byrne’s skeleton’ but believe it should be retained as ‘an integral part of the Hunterian Collection’.

Byrne has fulfilled half his wish – his body is no longer an ‘otamy’ on public show – but his request to be buried at sea remains so far unheeded.

Giant is at the Aldeburgh Festival Friday 9 & Saturday 10 June.

The full version of this article appears in the Aldeburgh Festival Book, available from the Box Office and Festival venues, 09-25 June.

Read next

Pavel Kolesnikov's Magic Box

Camille De Rijck talks to Aldeburgh Festival featured musician Pavel Kolesnikov about his fascination with American…

Something in the Water: Aldeburgh Festival moments that made it famous

Towering silent sentinels afloat on the Alde. Projections on a nuclear power station. Night walks and alfresco piano recitals at dawn. Aldeburgh…

Aldeburgh Festival Podcast

This weekly podcast gets up close with some of the artists taking part in the Festival. If you want to know more about the Aldeburgh Festival, this…