Scanning someone’s shelves is a quick way to find out their interests: their books and music provide a map of their mental world, and pulling something off the shelves often tells you something new about them. The climate-controlled audio-visual strongroom in the archive at the Red House holds, among other things, the record collection assembled by Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears and amidst the content one would expect (classical music, including their own music and that of their creative circle) there are unexpected items that shine a light on unfamiliar corners of their lives. Two LPs of Indigenous Australian music take us to the start of the 1970s and one of the projects destined to remain unrealised by the time of Britten’s death.

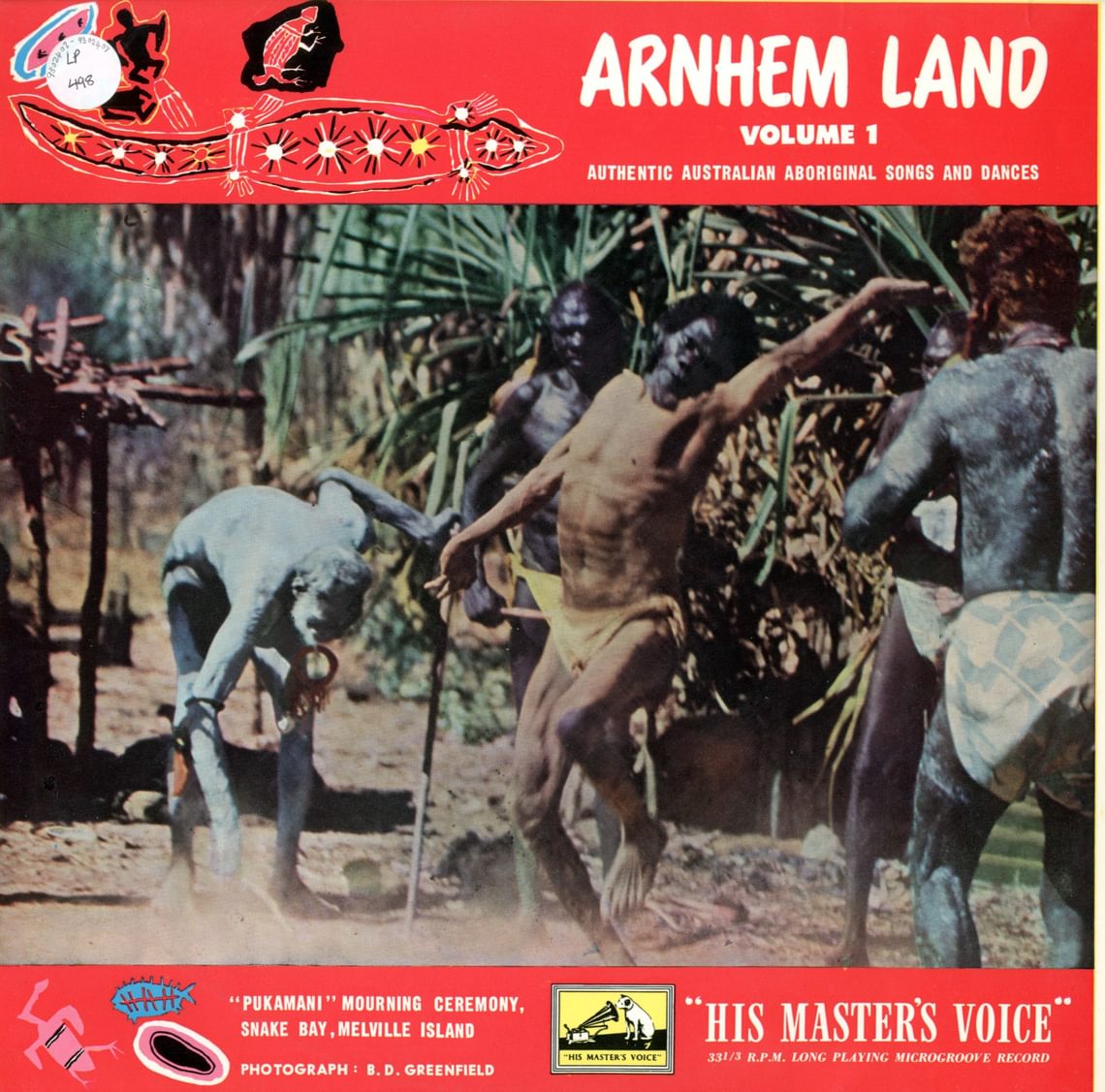

“Arnhem Land Vol.1: Authentic Australian Aboriginal Songs and Dances”, cover of LP released in 1957 of recordings made by A.P. Elkin; from Britten and Pears’ record collection.

In 1970 Britten and Pears accompanied the English Opera Group to Australia, in order to perform at the Adelaide Festival on a tour of Australia and New Zealand. They were accompanied by their Australian friends: the painter Sidney Nolan and the writer Cynthia Nolan, a couple to whom they had grown close in the 1960s, and after the Festival the two couples, accompanied by Princess Margaret of Hesse, swung into a tour of Australia and New Zealand, which took them to the major cities but also to the centre of the Australian continent, to Alice Springs and Uluru. (The tour itinerary can be seen plotted on a Google map at https://brittenpears.org/explore/research-and-collections/collections/brittens-travels/.)

In the centre of Australia Britten encountered Aboriginal culture and the landscape with which it was deeply involved. (The deep attachment to landscape, imbuing it with spiritual significance, is of course reminiscent of Britten’s own visceral attachment to the landscape of his native county: symbolically, at his funeral his grave at Aldeburgh church was lined with rushes from the reedbeds at Snape, fusing geography with spirituality.) He described it at the time in a letter home on April 5th 1970:

“We flew in a little 6-seated, one-engined, plane over the same striped desert, to a gigantic rock, bright red, standing completely isolated in the white & green bush. This was Ayers Rock [now known by its Aboriginal name, Uluru], which is sacred to the Aboriginals, their, so-to-speak, St. Peter’s Rome. The rock has curious shapes & marks all over it (made by nature not man) all of which have legends & myths told about them – one side would be where the carpet-snake men fought the poisonous-snake men, with marks showing the event; a mouth-like slit in the rock would be a wailing woman lamenting her dead son; rocks large and small in groups are the Mala men watching over the young initiates… We drove out in the twilight to look at this amazing Ayers Rock changing colour in the setting sun – from brown to deep purple, & back to scarlet.”

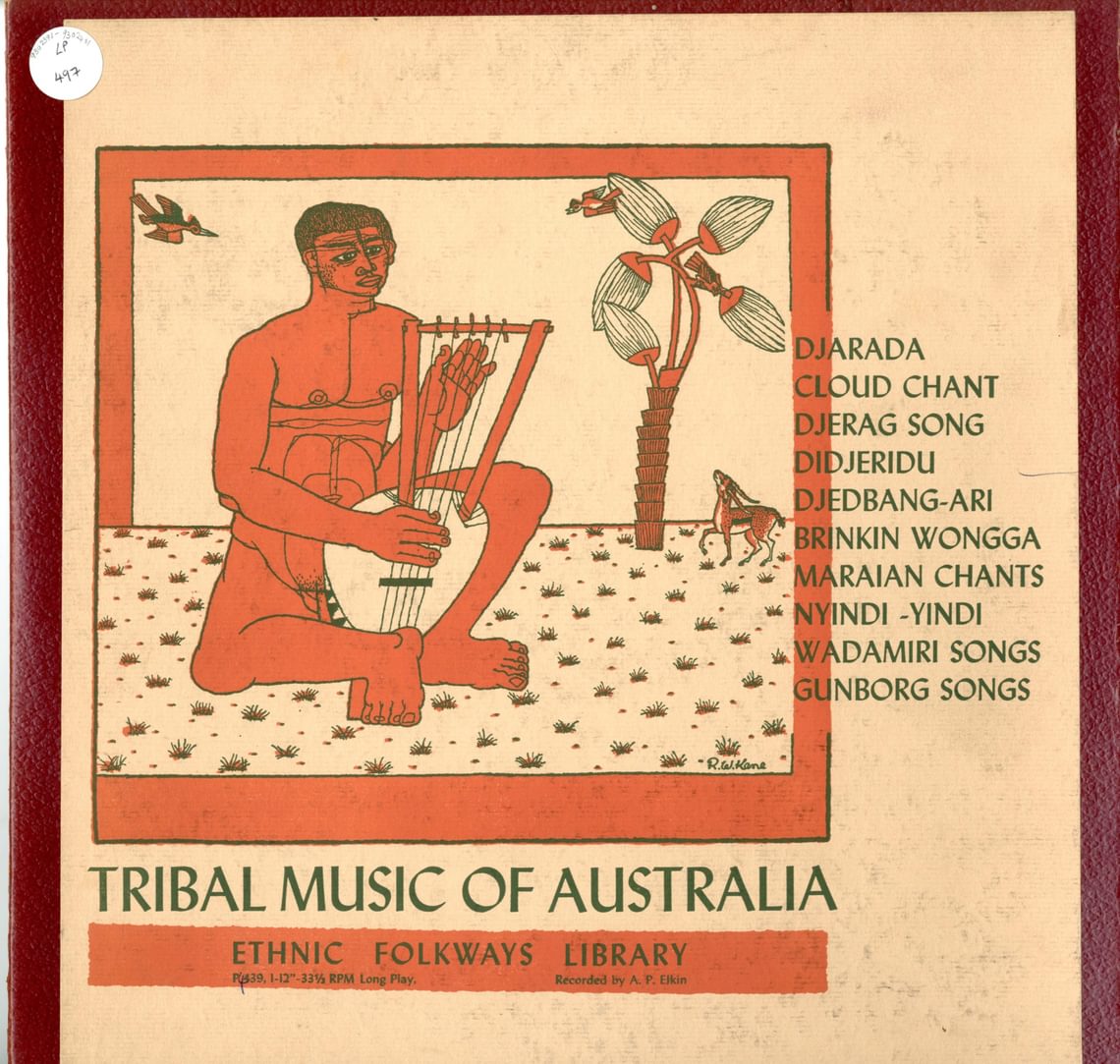

“Tribal Music of Australia”, cover of LP released in 1953 of recordings made by A.P. Elkin; from Britten and Pears’ record collection.

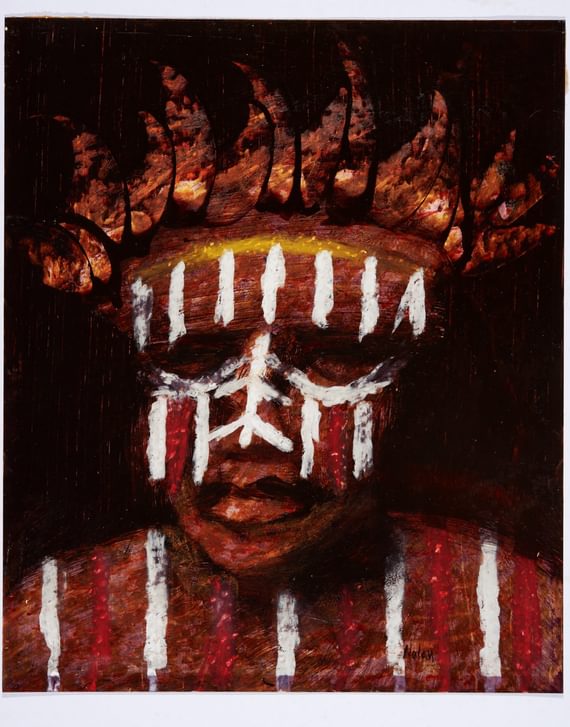

“Aboriginal Portrait” by Sidney Nolan, from Britten and Pears’ art collection.

They also encountered the issue of Aboriginals’ rights, the same letter describing meeting a campaigner who had devoted her life to “pleading their cause against people who chase them everywhere, depriving them of land which once was theirs” – Britten’s sympathy with the struggle against colonialism, seen in his support for causes such as the African National Congress, surfacing again.

Britten’s imagination was stirred, and later in that journey (at Townsville, Queensland) he and Sidney Nolan formed a scheme for a ballet, which would contrast the way young Aboriginal men came to manhood through initiation ceremonies with the way that Britten felt Western culture was failing its young. In the archive, Nolan’s typed scenario for the ballet departs from this initial scheme by omitting the Western elements and focussing on the elements drawn from Aboriginal life and myth. These were clearly the elements he felt were crucial and a series of paintings in the Red House showing Aboriginal motifs, made by Nolan in the months after their visit to Australia, show us what the visual world of the ballet might have been.

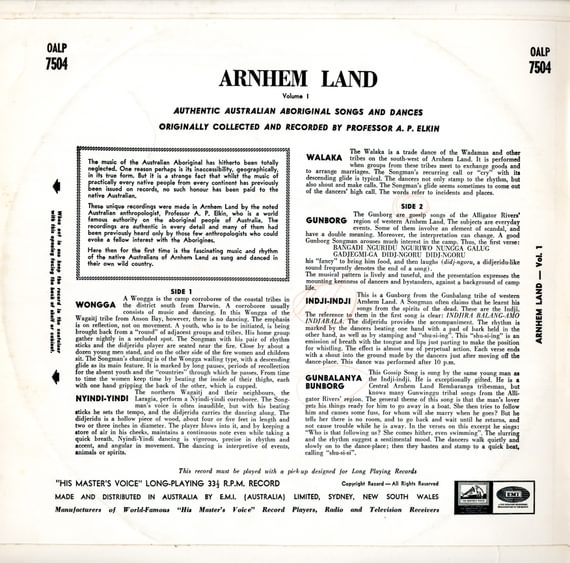

“Arnhem Land Vol.1: Authentic Australian Aboriginal Songs and Dances”, rear cover of LP released in 1957 of recordings made by A.P. Elkin; from Britten and Pears’ record collection, showing annotations possibly by Britten.

No music for the ballet was written, in the end: but the two LPs in the record collection are an indication of the sound-world on which Britten would have drawn (paralleling, of course, the way that Indonesian gamelan music fed, fifteen years earlier, into The Prince of the Pagodas). On the reverse of one LP sleeve we see markings and annotations, suggesting which particular pieces were sparking inspiration. For Britten, the wheels had started to turn and the process started that could have led, in time, to the production of a new work, maybe radically different from what he had done before.

We will, of course, never know whether if he had lived longer this project would have borne fruit: there are, in the archive, traces of a whole parallel career of Britten works, some of which advanced to the stage of musical sketches and others of which never got further than rough scenarios or vague ideas. Certainly within a few months his focus had shifted: in February 1971 a receipt records Britten buying a copy of “Death in Venice” at Aldeburgh Bookshop, and a month later a volume of Thomas Mann’s letters, as what was to be his last opera began to take shape. Had it not been for his declining health after that, and his death at only sixty-three, perhaps later in the 1970s Britten would have returned in his imagination to the red landscape of Uluru and brought this work to a conclusion. We can only wonder; these two LPs give us an idea of what the finished work might have drawn upon.

Image gallery

A gallery slider

Typed draft scenario for “The Initiation” ballet, by Sidney Nolan; from the Britten Pears Archive.

Typed draft scenario for “The Initiation” ballet, by Sidney Nolan; from the Britten Pears Archive.

Typed draft scenario for “The Initiation” ballet, by Sidney Nolan; from the Britten Pears Archive.

Typed draft scenario for “The Initiation” ballet, by Sidney Nolan; from the Britten Pears Archive.

- Dr Christopher Hilton, Head of Archive and Library