What if…?

The archive at the Red House documents, in remarkable detail, the lives and careers of Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears. Perhaps less obviously, it documents a whole parallel universe of the works that Britten did not compose: the ideas that were abandoned and the projects that were aborted. The archive, then, is a jumping-off point for speculation, a place that allows us to wonder, What if…?

The biggest counter-factual speculation of all, perhaps, lies not in a music manuscript or a fragment of libretto, but in an apparently mundane file concerned mostly with car insurance (reference BBD/2/28). It documents how, had things panned out differently, we might now be wondering about the possible career of a promising young composer who was born in Suffolk, was mentored by Frank Bridge, worked with W.H. Auden in the GPO Film Unit and died in a car crash, aged just twenty-three.

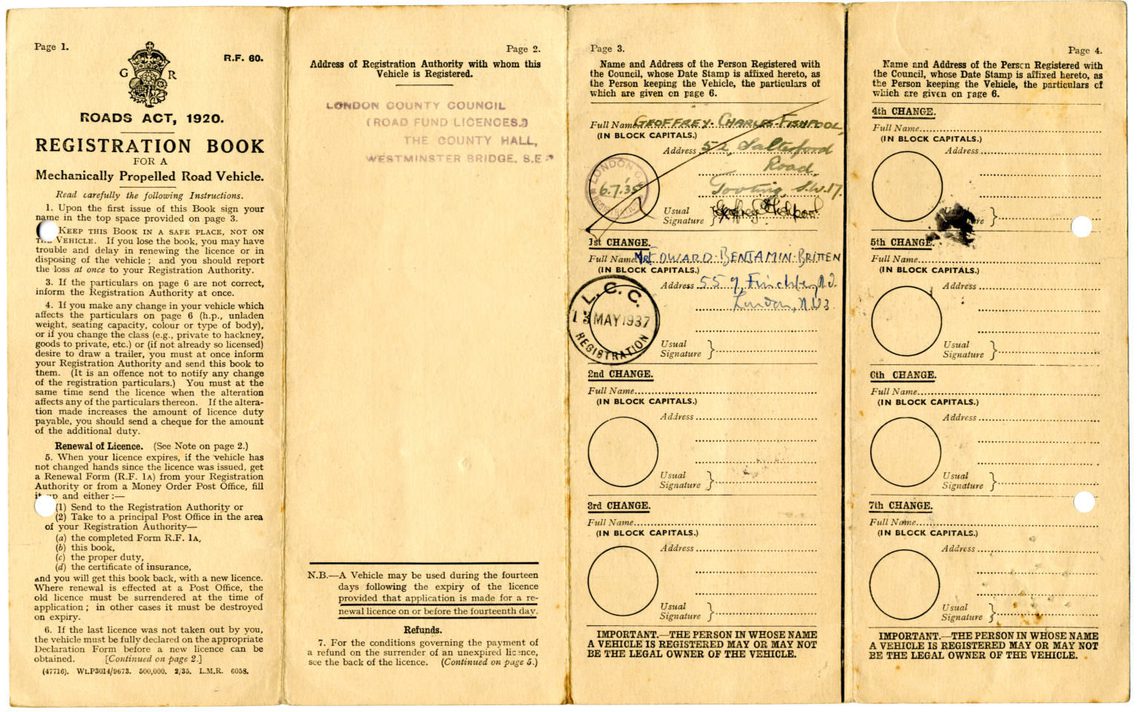

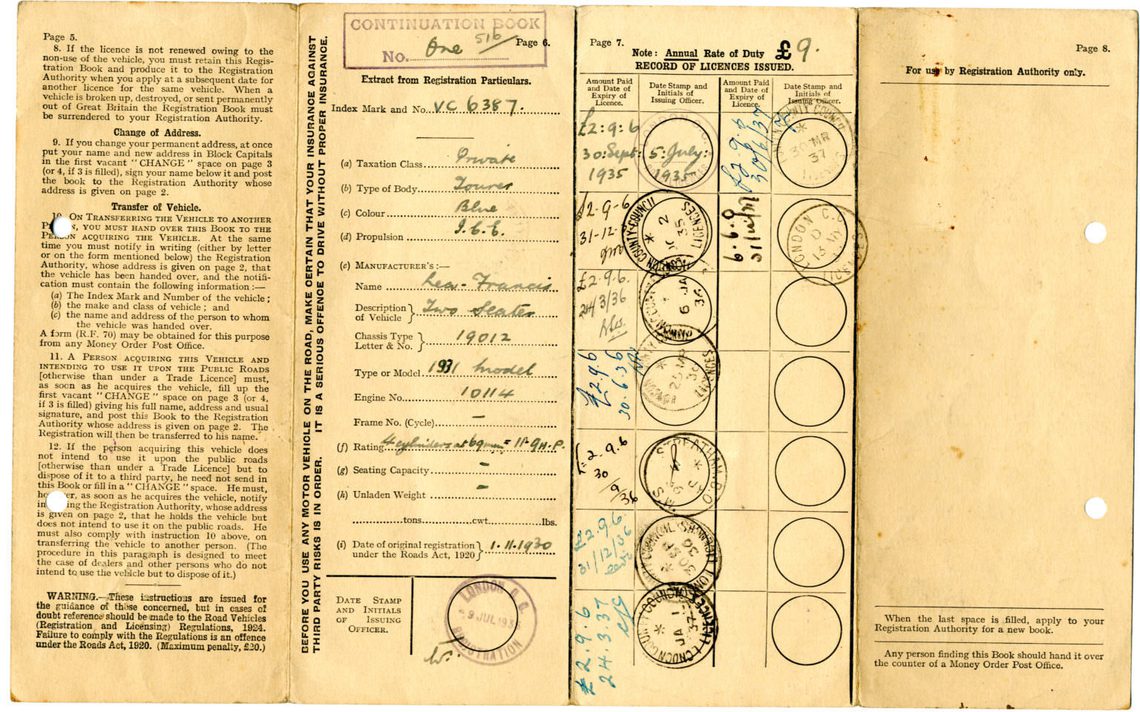

Benjamin Britten was always a car enthusiast: the archive documents a series of open-topped, sporty vehicles in which he raced about the Suffolk lanes. His first car, bought when he was twenty-two, was a relatively sober 1924 Lagonda. As soon as he could, however, he traded up: his legacy from his parents enabled him to buy a 1931 Lea-Francis two-seater. He took possession of the car on Thursday 13th May 1937 and the clock was already ticking towards the moment when the classic combination of a young man and a fast car brought trouble, as it so often does.

Side one of the Registration book of Britten’s newly purchased Lea-Francis.

Side two of the Lea-Francis Registration book.

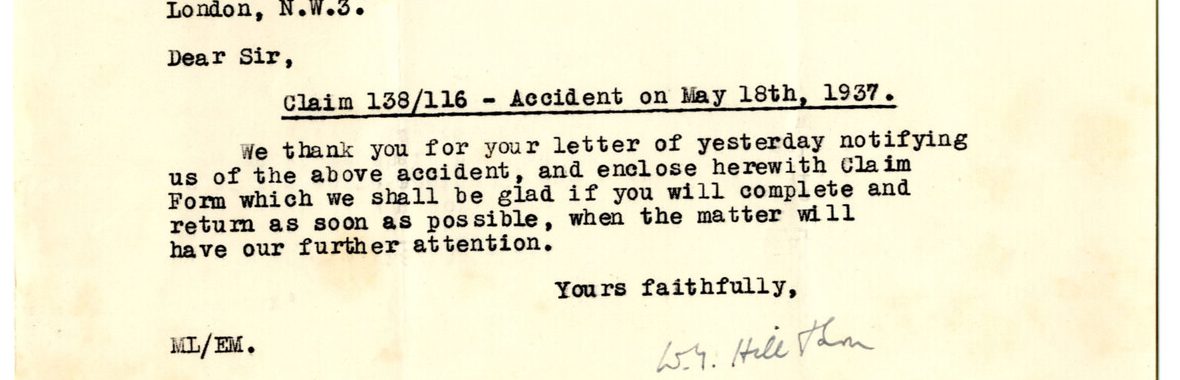

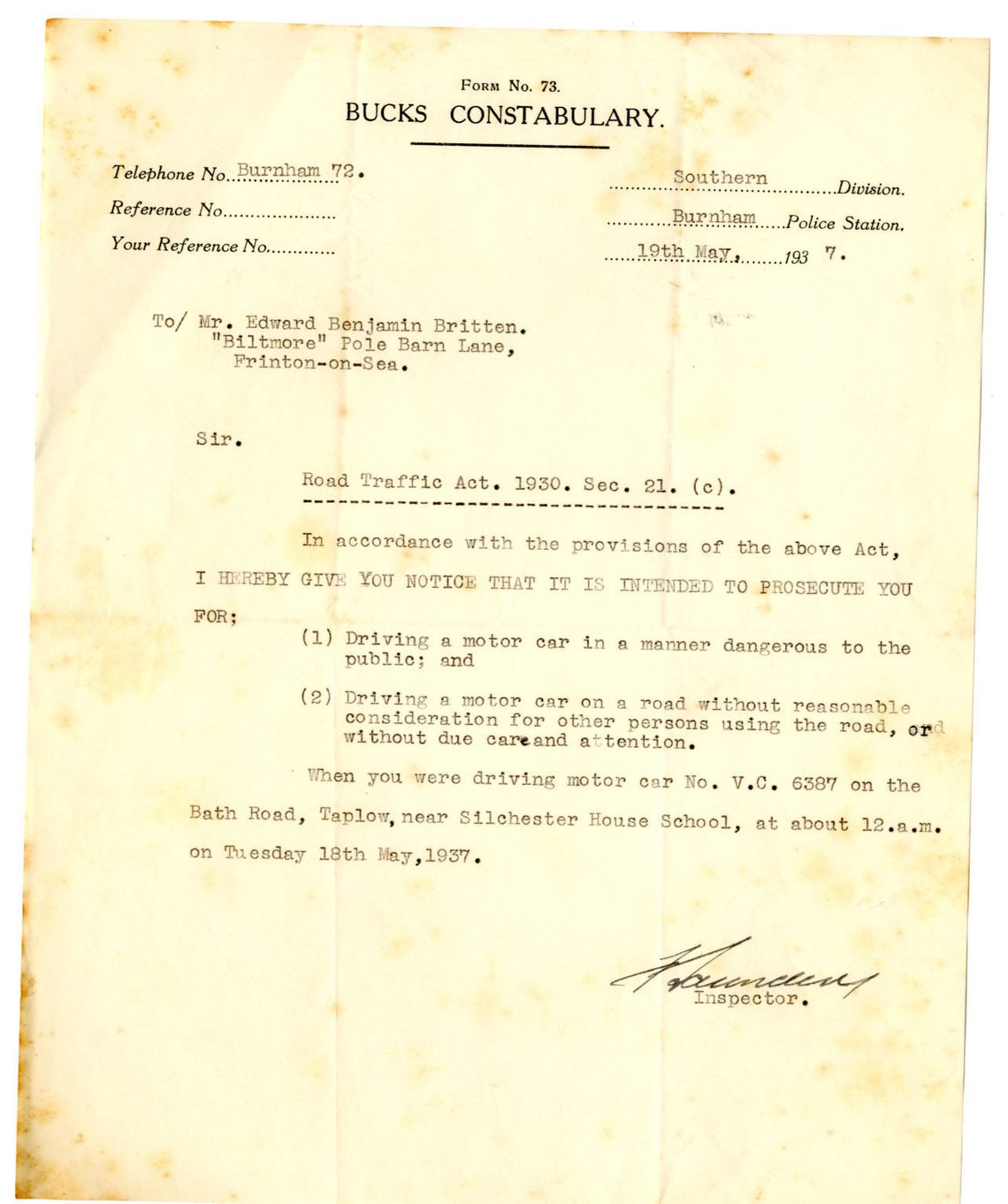

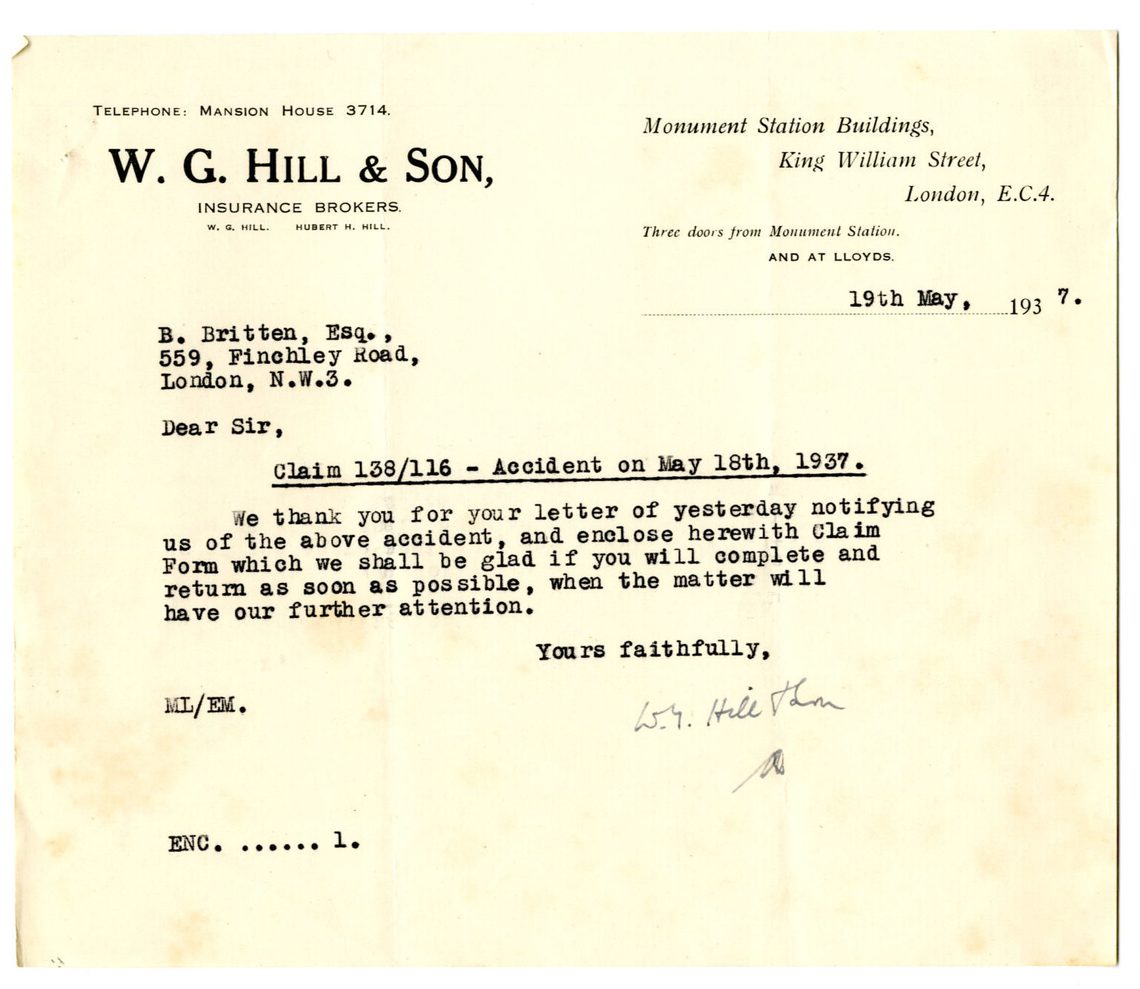

The first few documents in the file are a sedate record – car registration documents stamped to mark transfer of ownership and payment of licence fees, notes certifying the payment of insurance – but suddenly the story turns more dramatic, with a note from Britten’s insurance brokers regarding a claim arising from an accident on May 18th and, issued the next day, a notice from Buckinghamshire Constabulary that Britten is to be prosecuted for dangerous driving.

Bucks Constabulary’s notice of the accident.

Britten’s sister was present when the Lea-Francis was delivered on Thursday and Britten’s diary records that they spent the evening driving in north London, trying it out – there is the ominous note that “it is difficult to manage, but will be satisfactory I hope.” Brother and sister then drove out to the Cotswolds and spent the weekend there: they were returning late at night when the accident took place, on the A4 near Slough. The highway at that point took the form of a three-lane road, the centre lane being open for traffic in either direction to use for overtaking with neither direction having formal right of way (more about it here): this road layout has largely been abandoned in the United Kingdom now because of its obvious dangers, the central lane having been dubbed “the suicide lane”. The Brittens’ accident took a familiar form – they were in the central lane passing a vehicle when a large grey saloon heading in the opposite direction pulled out from behind a lorry and hit them head-on.

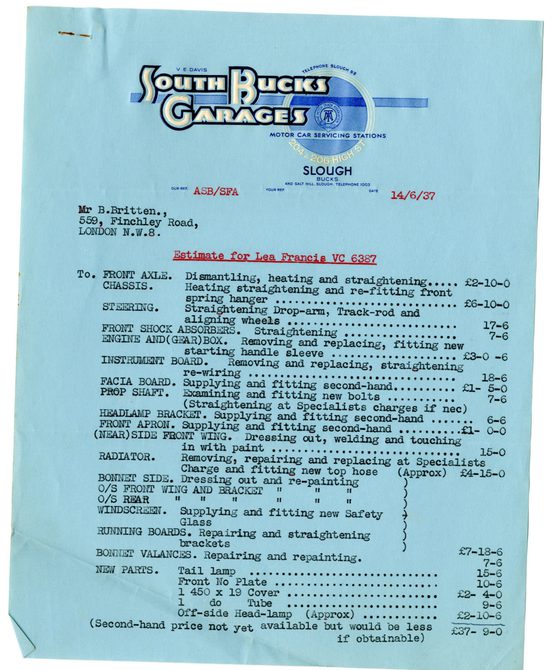

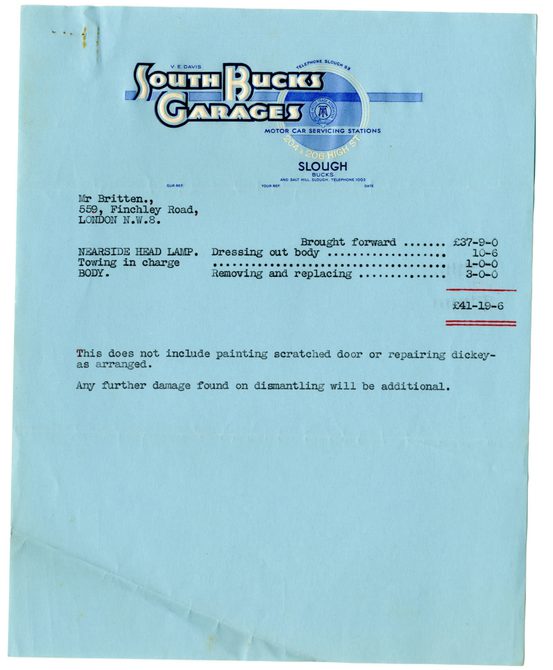

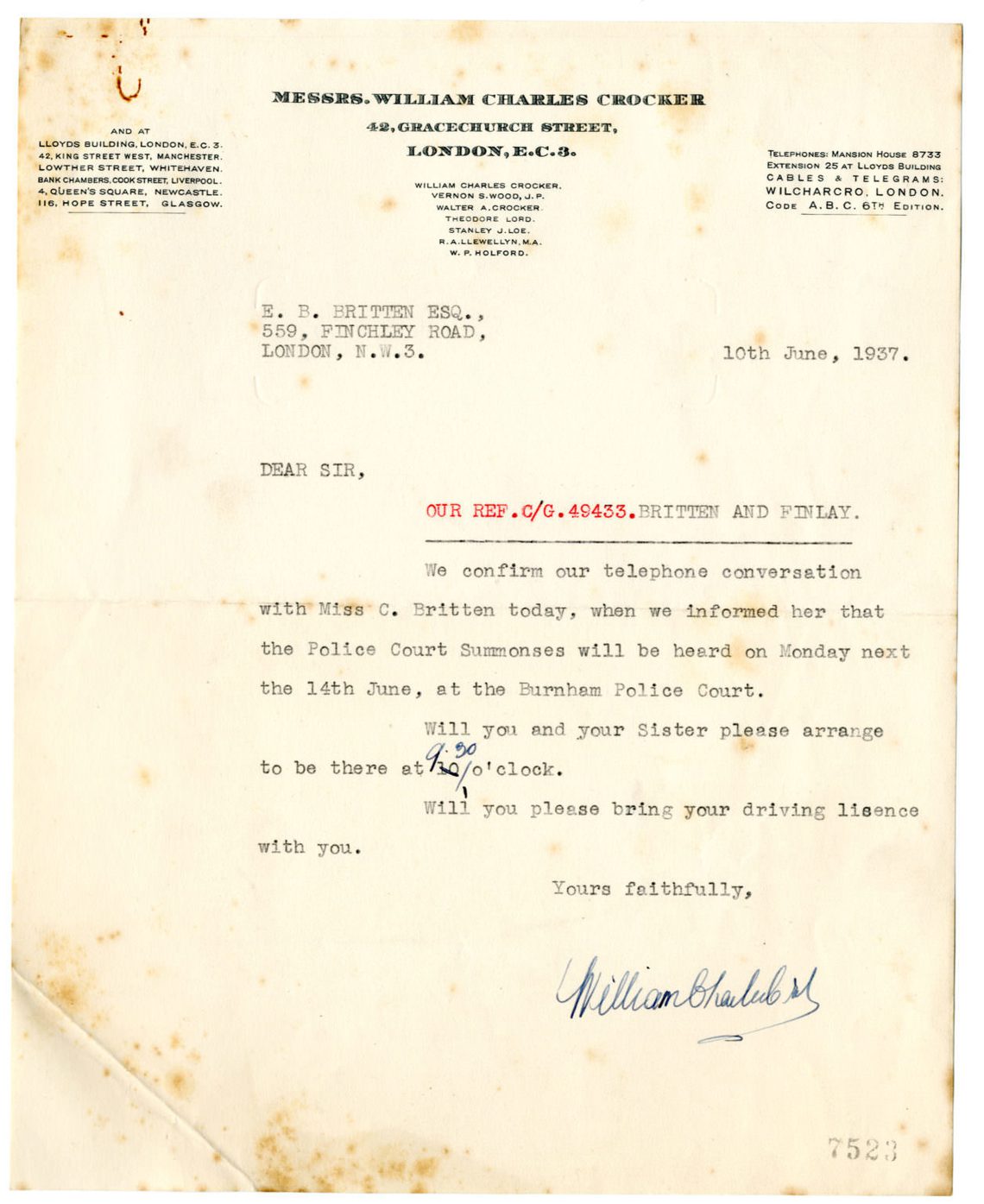

Amazingly, neither was injured seriously: Beth was flung out of the car and both she and her brother sustained cuts and bruises. Their luggage seems to have survived unscathed, too. The Lea-Francis, however, was in a bad state. It was removed to South Bucks Garage in Slough from where, some weeks later, Britten received a quotation for its repair. Using second-hand parts the garage felt that it could be repaired for a fraction under £42 (excluding repainting): given that Britten had bought it for £60, this shows what a hammering the car had taken.

Image gallery

A gallery slider

First page of the extensive quote to repair the damaged Lea-Francis.

Repair quote continued.

Final page of repair quote which doesn’t include painting over the scratched door – or any further costs incurred during the repair.

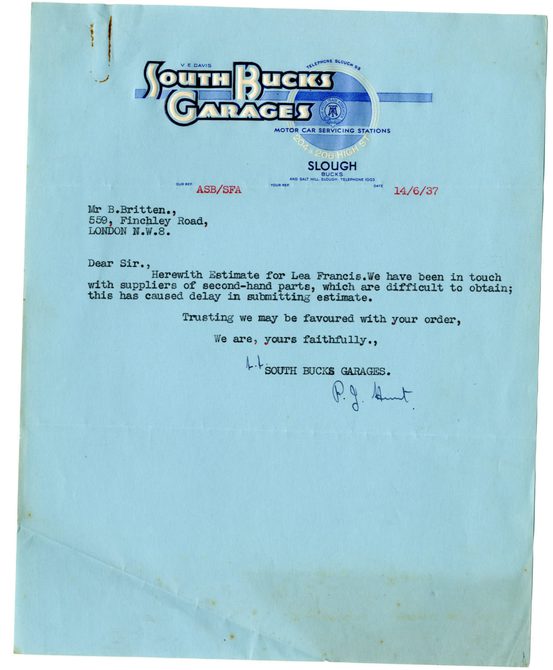

The immediate priority, of course, was the court case. It was scheduled for Burnham Police Court on 14th June 1937, where the two drivers would plead their cases: on the one side the young composer, and on the other the chauffeur of the Right Honourable Viscount Finlay.

Police Court Summons for the 14 June 1937.

Britten had had the bad luck to crash into the car in which a High Court judge was being chauffeured home. Understandably, his diary is tense: on 22nd May, following the notification of police action, he confided “It’s infuriating, because I know I was in the right. However with solicitors I may get off – but there is the infernal bother & worry of it all to be faced.”

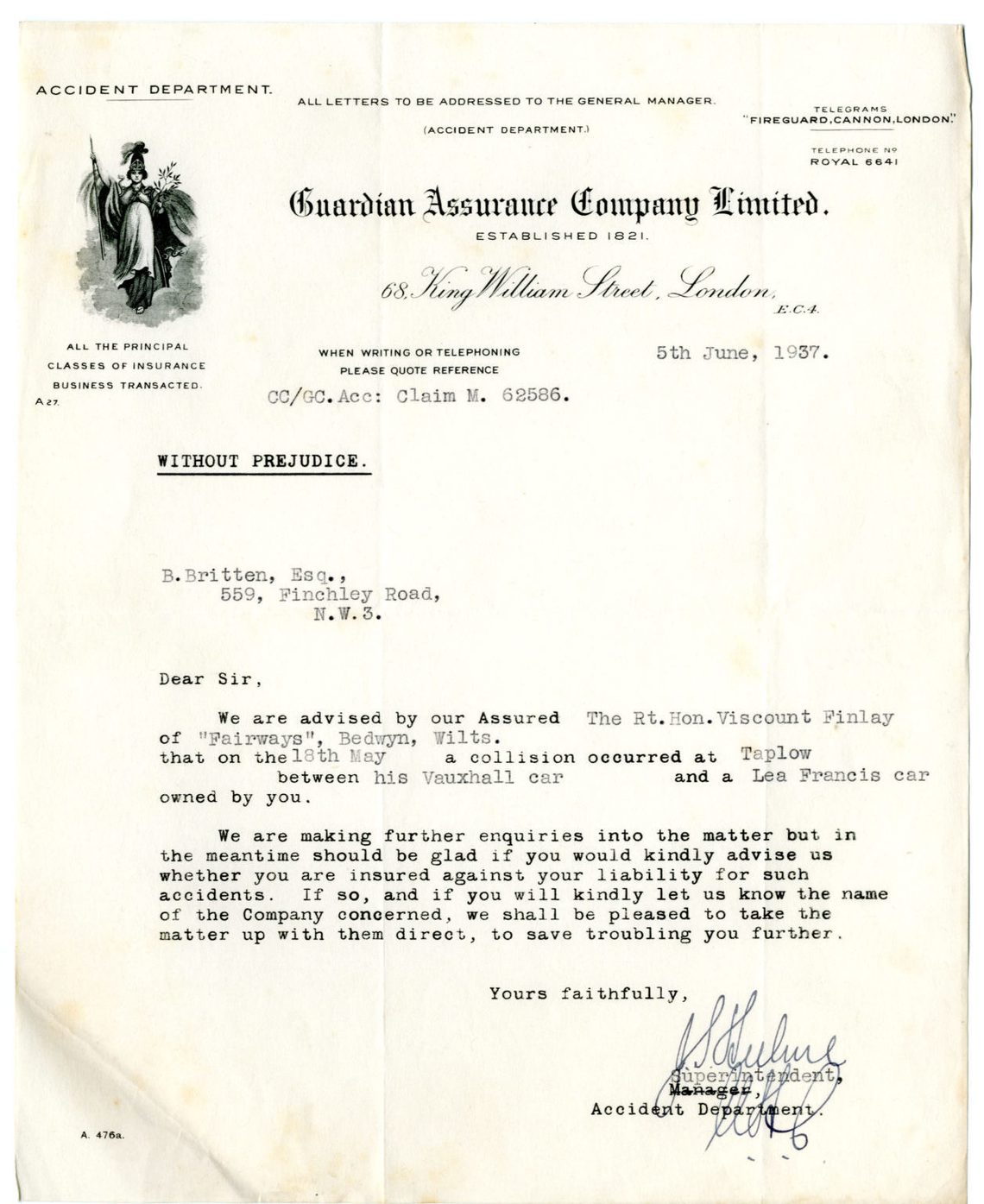

In the end, the case went well for him: it became clear that the judge’s chauffeur was in the wrong, pulling out into Britten’s path when the latter was already in the central lane, and the evidence was sufficiently clear that neither Britten nor his sister were required to take the witness stand. There was, still, the case of the Lea-Francis and whether it could be repaired. The rest of the file records the slow grinding of wheels as Britten’s insurers liaised with Viscount Finlay’s.

Note confirming that Britten’s insurers have been notified of his accident the day before.

Viscount Finlay’s insurers requesting contact details of Britten’s insurers.

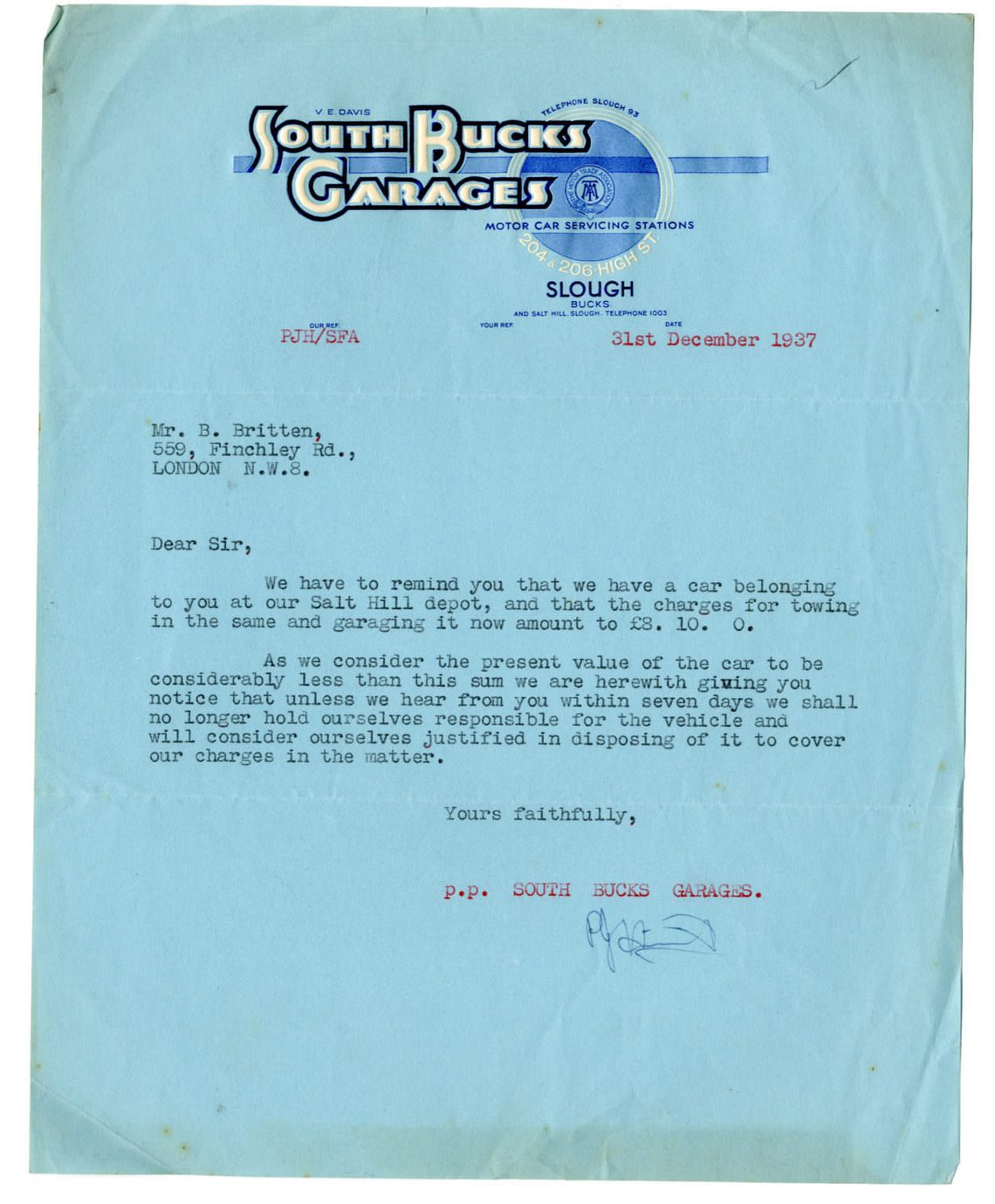

Reminder from South Bucks Garages that they still have Britten’s Lea-Francis in storage.

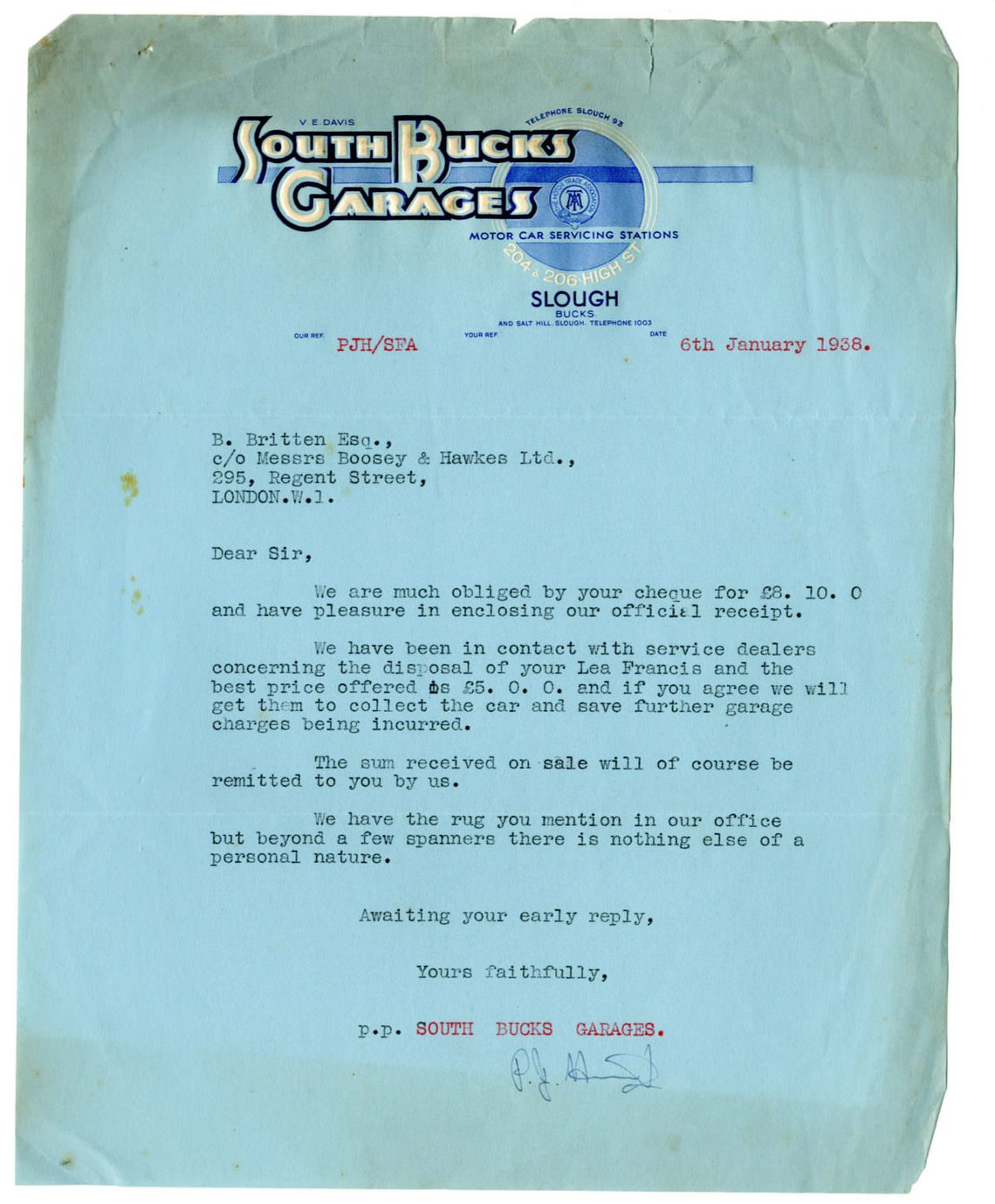

On December 31st South Bucks Garages write to remind Britten that the car is still in storage at their Salt Hill depot, having racked up storage charges of eight pounds and ten shillings, and that they would like to know, within a week, what is to be done about it; on 6th January 1938 they write again, thanking Britten for paying the storage bill and telling him that they have spoken to car dealers and will be able to dispose of the wreckage for £5. A rug and a few spanners are all that remains in the car belonging to Britten – these presumably will be forwarded to him, and after that the Lea-Francis will be removed, one assumes to be cannibalised for spare parts where possible and otherwise for scrap.

Confirmation of payment toward storage and confirmation that it will be scrapped for £5.

Not long afterwards Britten’s life took a different turn: he and Peter Pears left for the USA, and when they returned to the United Kingdom it was to a blacked-out country in which recreational motoring was a distant memory. Britten would be in his thirties before the chance to burn along an English road in an open-topped vehicle next arose. Posterity tells us that although no longer as young as he was when he hit the Viscount’s car outside Slough, he continued to seize every chance to drive fast with the wind in his hair. He never again came so close to ending his career in a crash; but it is down to luck that we do not find ourselves reading about the death of a young composer that night in 1937 and wondering, What if…?

- Dr Christopher Hilton, Head of Archive and Library