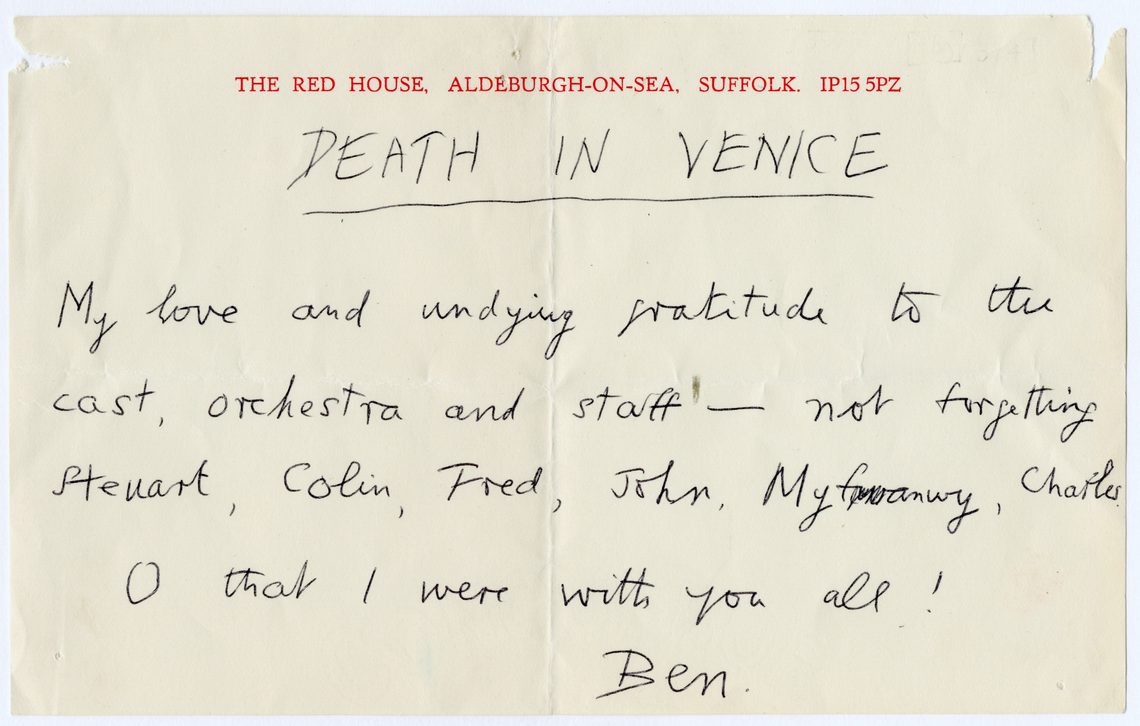

In our archive we hold a short note, in Britten’s frail hand, sent to Snape Maltings on the first performance of his final opera Death in Venice on 16th June 1973.

Britten sends his love to the company and wishes that he were able to be with them. He was unable to attend due to ill health. This was the first time Britten had not been present at the premiere of one of his operas - no doubt a terrible blow to him.

Britten taking a curtain call after the premiere of The Rape of Lucretia in 1946 .

Britten’s health had been progressively deteriorating during the composition of Death in Venice however he was determined to finish writing the opera before seeking the hospital treatment he needed. After completing the orchestral score in March 1973 he visited a cardiologist and following investigations was admitted to the National Heart Hospital in London for an operation on 7 May.

Rehearsals for the first production began without him and with Steuart Bedford conducting. Britten had conducted just six of the premieres of his eleven operas before Death in Venice so handing over the baton was not unusual for him. He knew that the opera would be in good hands – Bedford had been an integral member of the English Opera Group since 1967 and was also well prepared.

In an interview for The Times, Bedford explained that he and Britten had ‘been right through the score and talked a great deal about it, and what he has in mind. He usually changes many things when he sees it all unfolding before him. This time Colin Graham, who is producing, and I have had to make the decisions ourselves. It may be something of a strange experience for Britten when he does see it, probably the first time he has had nothing to do with the preparation of one of his stage works.’

Britten returned home from hospital on 1st June and began his long convalescence. He was not well enough to attend rehearsals but was kept informed on progress at Snape Maltings. On the night of the opera’s premiere Britten was at his country cottage in Horham on the Norfolk border (with his housekeeper Nellie Hudson and a nurse) where he was staying to avoid the bustle and stress of the Aldeburgh Festival. This was the first time he had missed a Festival. A second performance was given on Pears’s birthday, 22nd June, and broadcast live from the Maltings however Britten found himself unable to listen to it. He saw his new opera for the first time on 12th September when a special performance was arranged for him at Snape Maltings.

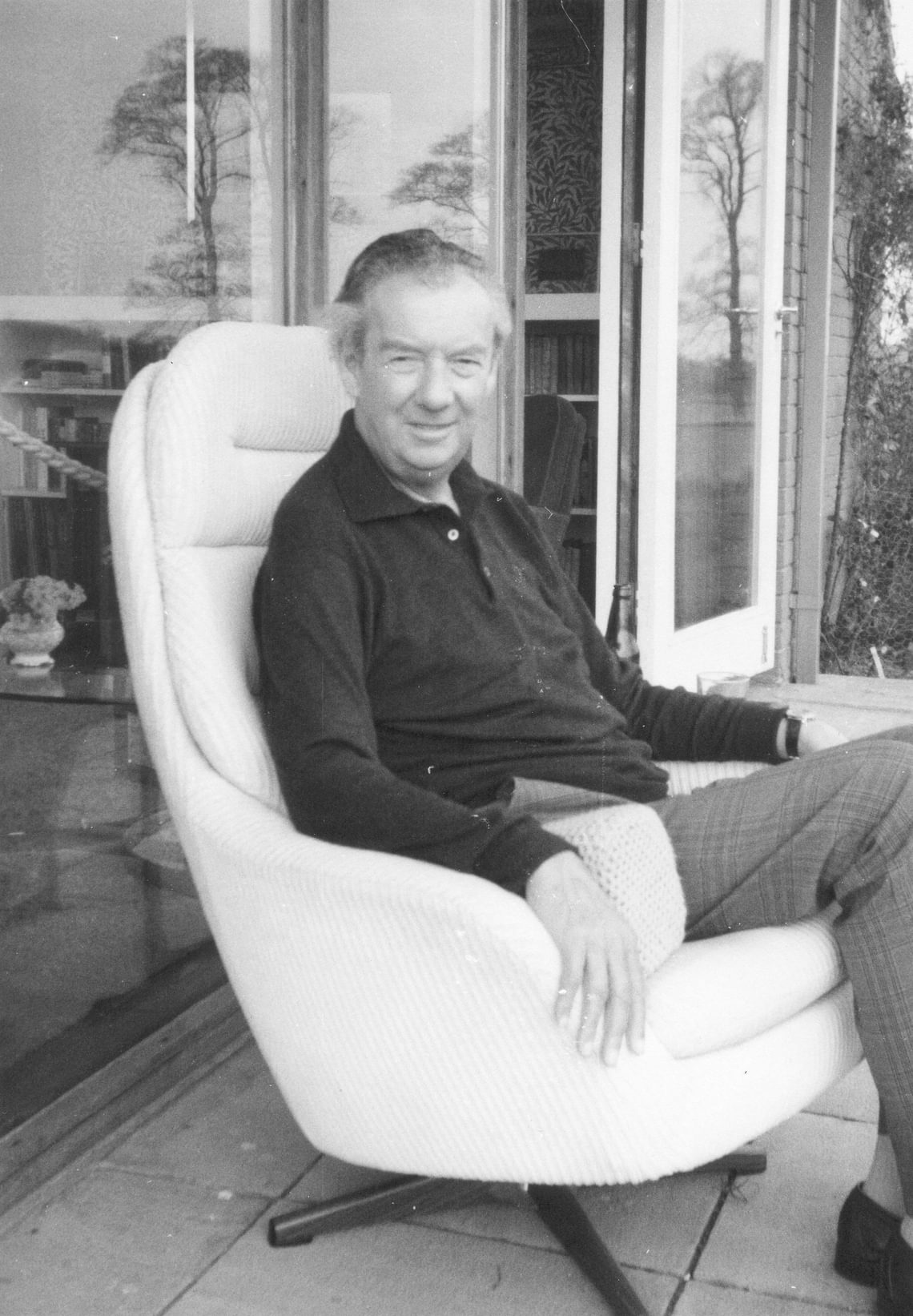

Photograph of Britten at Horham taken by Rita Thomson in spring 1976 .

Britten was making a very slow recovery and finding writing as well as playing the piano very difficult. Rita Thomson, the senior sister whom Britten had befriended at the Heart Hospital, visited the Red House during Easter 1974 and with her help and care he was able to attend the recording sessions of the opera at Snape Maltings and talk through each take with Bedford and the singers.

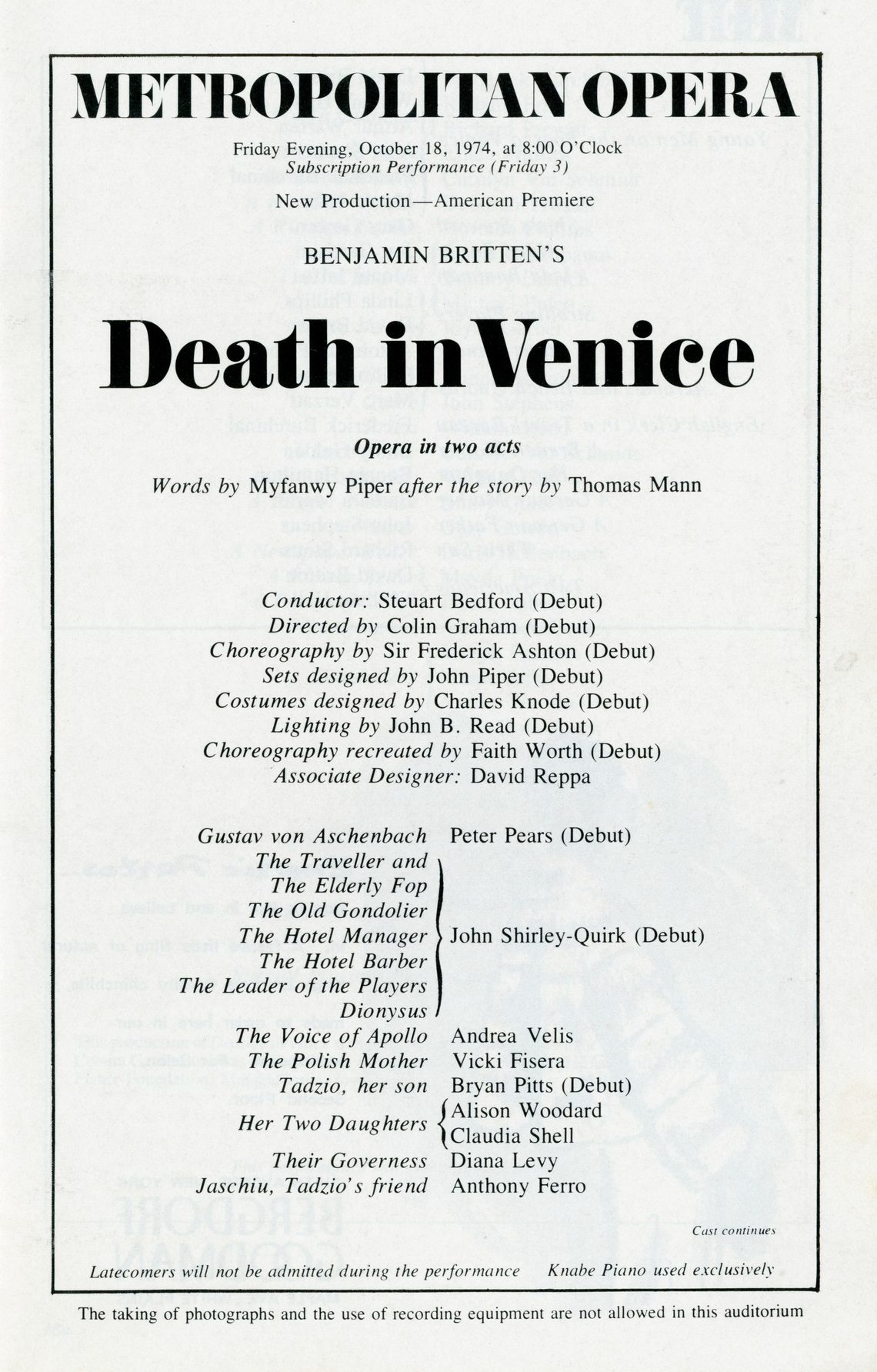

Thomson soon moved to the Red House to provide the full-time care Britten needed and so was with him, in autumn 1974, when Pears was in New York for nearly three months for a season of Death in Venice at the Metropolitan Opera House. This was Pears’s debut at the Met as well as that of colleagues Bedford, Graham, John Shirley-Quirk, Frederick Ashton and designers John Piper and Charles Knode as the original production was moved to America. Britten was too frail to travel to New York – he went instead with Thomson to stay with their close friend Peg Hesse at her home Wolfsgarten in Germany.

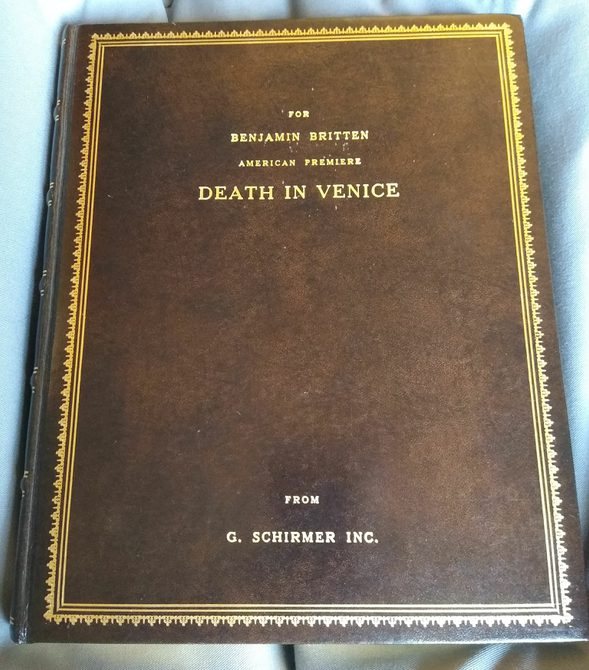

Programme for the American premiere of Death in Venice.

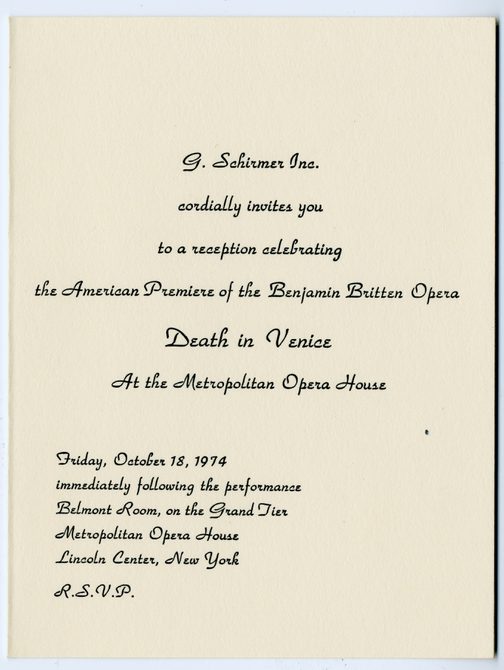

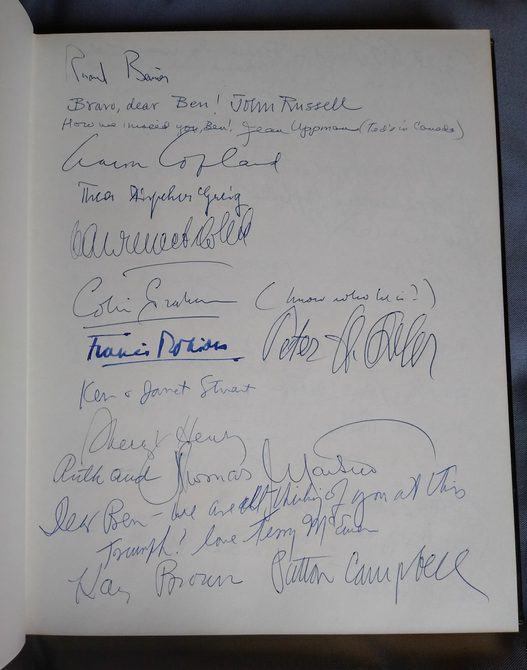

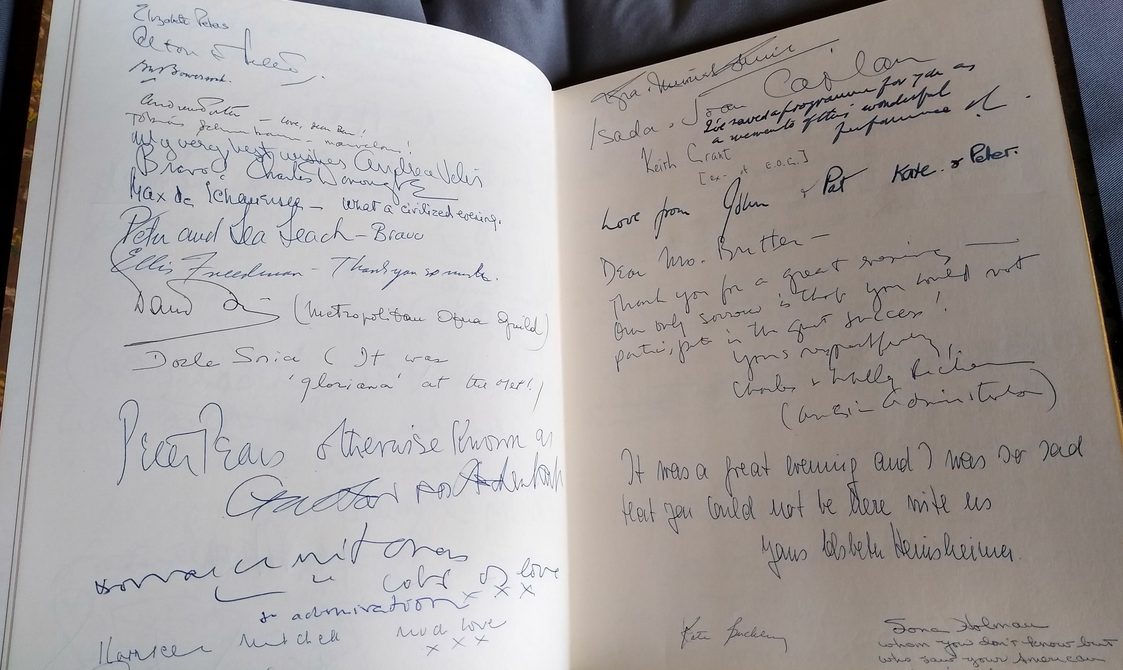

At a celebratory reception held after the American premiere on 18th October the attendees signed a book as a gift to the absent composer. Pears amusingly signed the volume ‘Peter Pears otherwise known as Gustav von Aschenbach’. Britten was frustrated and upset, not only for missing the occasion, but also as he came to accept that he would never make a full recovery. He wrote to his sister Beth of his feelings on the day before the American premiere - ‘very jealous of them all in New York for D in V. It is one of the hardest things to take.’

Image gallery

A gallery slider

Invitation to the New York reception.

The volume presented to Britten.

Signatures of guests at the reception including Aaron Copland.

Signatures of guests at the reception including Gustav von Aschenbach.

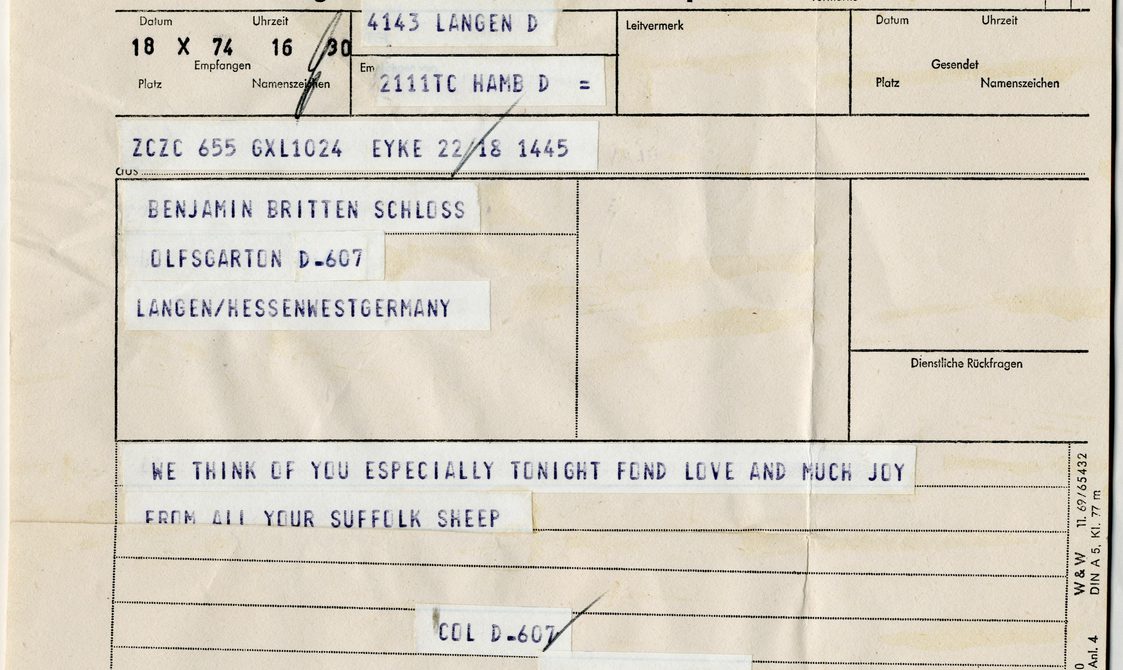

Telegram sent to Britten at Wolfsgarten found in the volume.

The opera was a great success in New York. Britten had some time ago decided to avoid reading newspaper reviews. Indeed, Pears later wrote in reply to a critic apparently barred from Aldeburgh Festival events that 'Britten had a great distrust and shyness of critics in general'. Britten therefore relied on reports of rehearsals and performances in New York in letters from Pears and friends. And when Pears rang him to tell of the success of the first night, he reported that Britten ‘was only concerned to know how they had liked me – dear Ben!’

With Thomson’s dedicated care and friendship, Britten was able, despite his continuing poor health, to resume composing as well as to take a limited part in the Aldeburgh Festival and some trips abroad. Photographs from this time typically show Britten linking arms with Thomson for support or her sitting attentively close at hand.

Janet Baker, Britten and Bedford rehearsing Phaedra with Thomson watching on, June 1976.

Credit: LuckhurstThe audience felt Britten’s absence once again when the Amadeus Quartet premiered his String Quartet No. 3 at Snape Maltings on 19th December 1976, just 15 days after his death. The composer had been able to hear the work when the Quartet visited the Red House at the end of September to prepare the piece with him. Cellist Martin Lovett described the first performance as a ‘voice from the grave’ – its success due in no small part to the guidance received from Britten three months earlier. Today Britten’s presence endures in his music and in our work at Snape Maltings and The Red House.

Judith Ratcliffe, Archivist

Read next

Archive Treasures: The story of a Holocaust survivor and a musical legacy

We mark the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II, and of the liberation of the death camps with the story of a special…

Archive Treasures: Armenian Amphora

Among the many treasures on display at the Red House is the splendid Armenian amphora. It dates from the Urartu era, a civilization which, from the…

Archive Treasures: The English Opera Group

The English Opera Group collection forms part of the Britten Pears Arts Archive which documents the lives and work of Britten and Pears, as well as…