James Callaghan, Roy Jenkins, Barbara Castle: the list of Ministers in Harold Wilson’s 1964-1970 Labour government in the UK includes many political titans who would go on to shape politics into the 70s and 80s. In particular, there is an argument that as Home Secretary Roy Jenkins did as much as anyone to shape the modern United Kingdom, steering through abortion law reform, the decriminalisation of homosexuality, the end of theatre censorship and the abolition of the death penalty. Behind these towering figures, however, stand other less well-known ministerial figures, their names known, if at all, by the politics devotee, and forgotten by the general public. Our Archive story here takes in one such figure: Kenneth Robinson (1911-1996), Minister of Health in the Wilson government from 1964 to 1968.

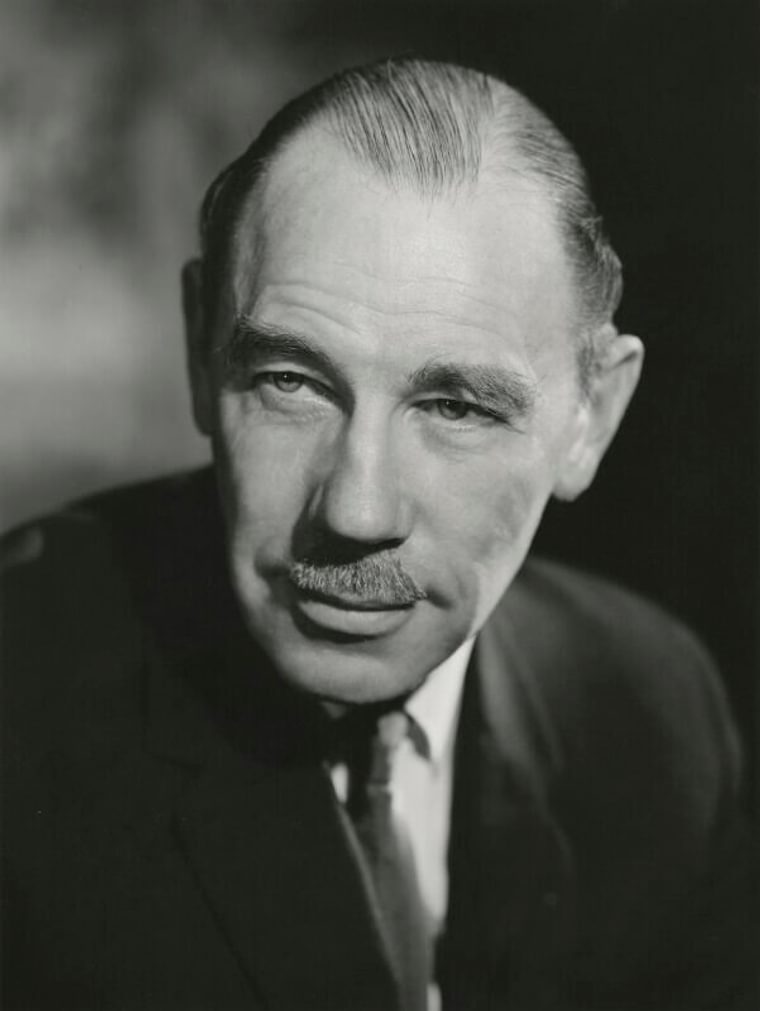

Kenneth Robinson MP (photograph by Walter Bird, 1964; © National Portrait Gallery, London, made available under Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0))

Robinson’s story is a fascinating one, and he should probably be better remembered than he is today. He was born into the middle class, the son of a doctor and nurse, and attended public school until he was 15. At this point in his mid-teens, however, his father died and his mother, now unable to meet the costs, had to withdraw him from school: this was the end of Robinson’s formal education. After various clerical jobs, when the Second World War came he joined the Royal Navy as an ordinary seaman and rose to Lieutenant-Commander. He entered Parliament via a by-election in 1949. In the course of his political career, first in opposition and then as a highly-regarded Minister for Health, he pushed for the decriminalisation of homosexuality, the removal of attempted suicide from the list of crimes, and the ending of tobacco advertising on television.

Robinson was described as one of the few Ministers of Health that was felt by the medical profession to understand them, perhaps because of his own family background, but his interests were not purely medical: leaving politics at the end of the first Wilson government, he served Chairman of the English National Opera from 1972 to 1977, and of the Arts Council of Great Britain from 1977 to 1982. We do not know how he met Britten, but their shared interest in opera and the arts in general clearly brought them into the same social circles. A letter from Britten, dated 18th May 1965, takes up the story:

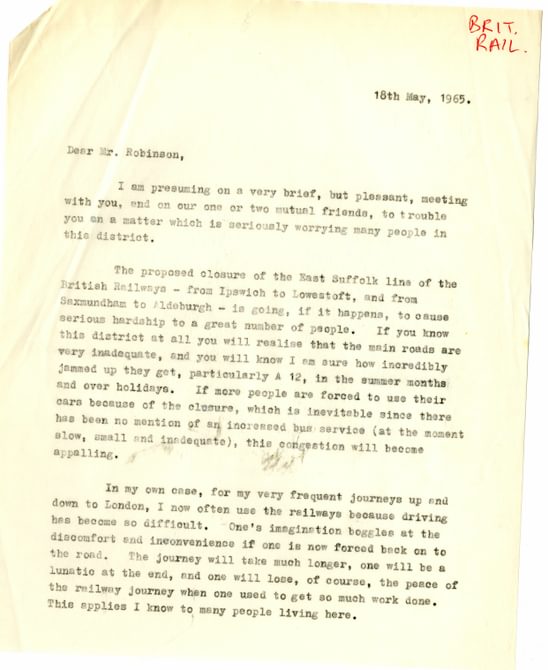

“Dear Mr Robinson,

I am presuming on a very brief, but pleasant, meeting with you, and on one or two mutual friends, to trouble you on a matter which is seriously worrying many people in this district…”

Britten’s concern is for a matter that lies outside Robinson’s ministerial brief, speaking to the social changes of the 1960s but in another area:

“The proposed closure of the East Suffolk line of the British Railways – from Ipswich to Lowestoft, and from Saxmundham to Aldeburgh – is going, if it happens, to cause serious hardship to a great number of people.”

A little over two years before, British Railways had published the report “The Reshaping of British Railways” – usually referred to as the Beeching Report after Dr. Richard Beeching, Chairman of the British Railways Board. Beeching’s remit was to stop the railways running at a loss and as part of this task he proposed 2,363 stations and 5,000 miles of railway line for closure (this accounting for 55% of stations and 30% of the network’s route miles). Many rural lines were closed; duplicate routes that had emerged during the railways’ unplanned nineteenth-century developed were stripped out; and on surviving lines, many little-used stations were removed to allow faster movement of the trains that remained. The “Beeching Axe” remains hugely controversial to this day. On the one hand, it brought modernisation to an industry still operating in some ways as it had in the nineteenth century (Beeching identified block trains carrying large amounts of the same material on the same journey as the future of rail-freight, rather than trains composed of individual wagons heading for different destinations that had to be broken up and reshunted on a regular basis). On the other, it crystallised and made permanent the conditions that applied to a very particular moment in time – when mass car ownership was expanding without a clear picture of how, in future, we might come to see that as a curse as well as a blessing, and seek to reduce car traffic – and, crucially, it was charged only to look at profit and loss, not at social good. Railways that brought social or environmental benefits that outweighed the fact that running them incurred financial loss were outside Beeching’s remit.

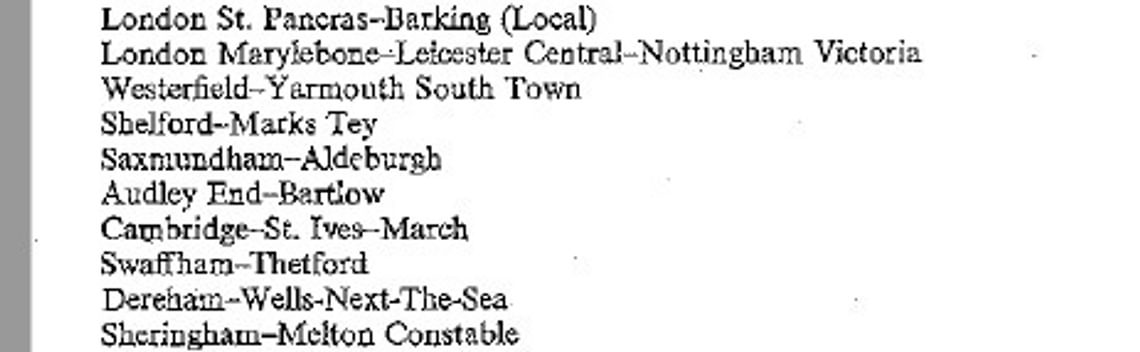

Page 102 of “The Reshaping of British Railways” begins the litany of proposed closures, starting with a list of lines from which passenger services are to be withdrawn. (The full list runs for many pages: the report in its entirety can be seen here). On page 105 are listed “Westerfield - Yarmouth South Town” and, two entries below, “Saxmundham – Aldeburgh”: the line up the Suffolk coast from the edge of Ipswich to Lowestoft and Yarmouth, and the spur that carried passengers from that line down to the sea at Aldeburgh. At a stroke, Aldeburgh (and its Festival-goers) would go from having its own station, to using Ipswich station some twenty-five miles away as their railhead.

“The Reshaping of British Railways”, or the Beeching Report: extract from the list of lines to be closed (British Railways Board, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Britten’s letter sets out the problems he foresees if the railway is closed:

“If you know this district at all you will realise that the main roads are very inadequate, and you will know I am sure how incredibly jammed up they get, particularly A 12, in the summer months and over holidays. If more people are forced to use their cars because of the closure, which is inevitable since there has been no mention of an increased bus service (at the moment slow, small and inadequate), this congestion will become appalling.”

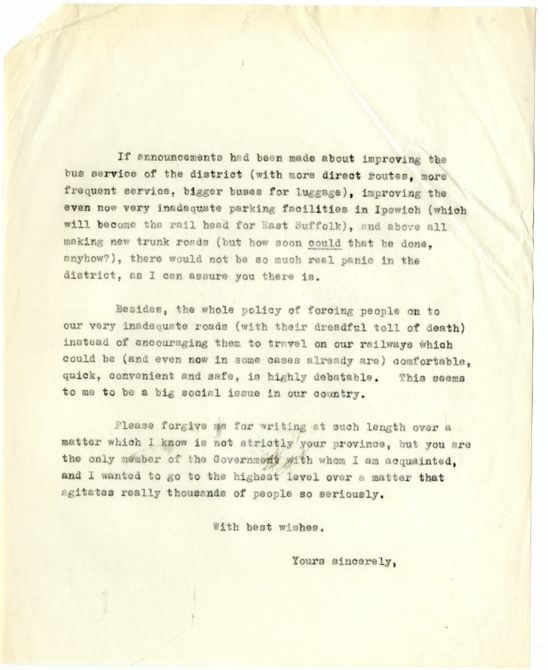

He explains that public disquiet could perhaps have been allayed by announcements of improved bus services, better parking at Ipswich station, and improvements to trunk roads, but none of these had been forthcoming and as a result the public were facing withdrawal of the railway service with nothing new promised to take its place.

Besides, he continues,

“…the whole policy of forcing people onto our very inadequate roads (with their dreadful toll of death) instead of encouraging them to travel on our railways which could be (and even now in some cases already are) comfortable, quick, convenient and safe, is highly debatable. This seems to me to be a big social issue in our country.”

Image gallery

A gallery slider

Letter from Benjamin Britten to Kenneth Robinson MP, May 1965

Letter from Benjamin Britten to Kenneth Robinson MP, May 1965

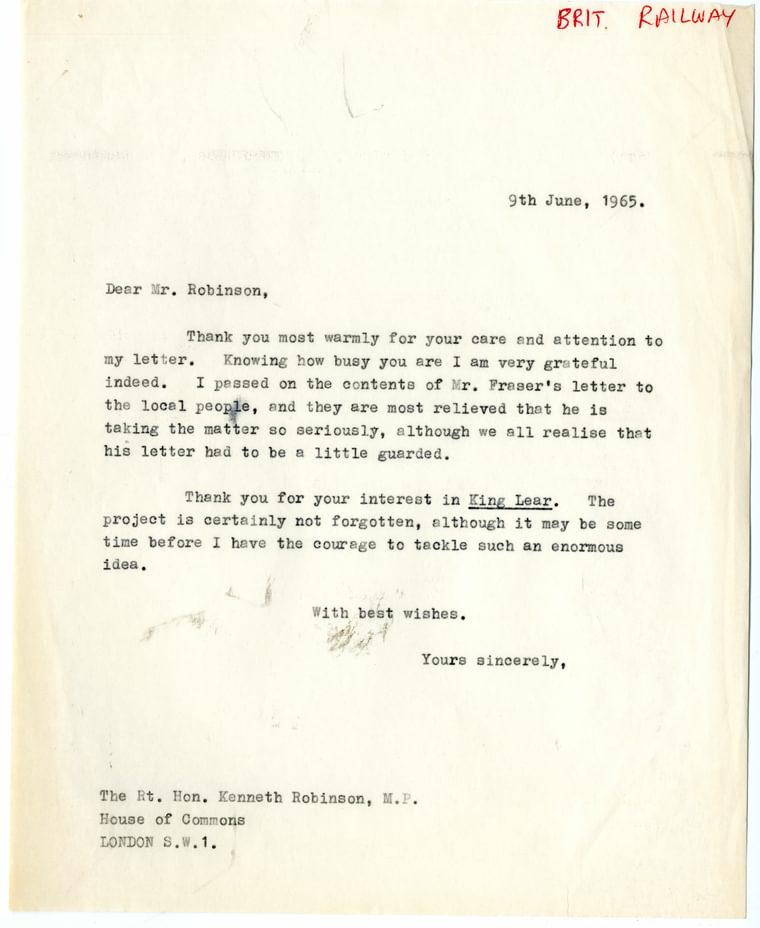

Robinson’s reply is not held in the archive but a carbon of Britten’s thank-you note is. Tom Fraser, the Minister of Transport, had apparently written allaying Britten’s fears in some way: “I passed on the contents of Mr Fraser’s letter to the local people, and they are most relieved that he is taking the matter so seriously, although we all realise that his letter had to be a little guarded.”

The contents of Tom Fraser’s letter are not known, but in the end Britten was asking for something that lay outside the government’s considerations at this time: Beeching had been charged with looking at profitability, not social good, and most of Britten’s objections focussed on the latter. Although the political colour of the government had changed since Beeching’s report, the Labour government did execute most of its recommendations (and indeed closed some lines that even Beeching had not mentioned). In coastal Suffolk things were not quite as drastic as Beeching had proposed, in that the East Suffolk line survived from Ipswich to Lowestoft (the section beyond here to Yarmouth was lost), by dint of stripping back costs to the minimum (making stations unmanned, converting much of the line to single-track, reducing the standards of maintenance so that the maximum speed and weight of trains had to be lowered, and so forth). For the Saxmundham-Aldeburgh branch, however, there was no reprieve. The last train ran on September 10th 1966; the journey was captured on film and can be seen on the website of the East Anglian Film Archive here. Passengers for Aldeburgh are left with the buses from Saxmundham, running hourly (but not on Sundays or in the evenings). Much of the A12 in Suffolk remains single-carriageway and dotted with roundabouts, but the roads, and private cars, are the only feasible ways for much of the county to get from A to B: there has been movement towards reopening some of the lines closed in the 1960s, but the railway network remains essentially the one that Beeching created. Reading Britten’s letter, we can fantasise about a world in which Festival-goers could get off the train at Saxmundham and board a sleek, modern train for the short journey to the coast, but in Beeching’s world that was never going to happen.

Britten’s letter acknowledging Tom Fraser’s also mentions, very briefly, another might-have-been: in response to a comment from Robinson, he replies

“Thank you for your interest in King Lear. The project is certainly not forgotten, although it may be some time before I have the courage to tackle such an enormous idea.”

Letter from Benjamin Britten to Kenneth Robinson MP, May 1965

Britten and Pears had begun planning an opera based on Shakespeare’s King Lear in the late 1940s, and within the archive we hold copiously-annotated copies of the Penguin edition of the play, with lines struck out and others highlighted for retention in the libretto. The project faltered when the press got wind of it and, feeling pressurised, Britten put it to one side, instead delivering Albert Herring(a total contrast in tone). The idea was never abandoned, as this correspondence from nearly twenty years later indicates; perhaps, had Britten stayed healthy for longer into the 1970s, he would eventually have returned to it. Maybe in some parallel universe people are planning to travel to this year’s Aldeburgh Festival, by train, in order to hear Britten’s King Lear: just one of the fascinating possible futures that the archive holds.

Dr. Christopher Hilton, Head of Archive & Library

Our thanks to Disused Stations for permission to use photographs of Aldeburgh station.

You might also like

Archive Treasures: The story of a Holocaust survivor and a musical legacy

We mark the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II, and of the liberation of the death camps with the story of a special…

Archive Treasures: Armenian Amphora

Among the many treasures on display at the Red House is the splendid Armenian amphora. It dates from the Urartu era, a civilization which, from the…

Archive Treasures: The English Opera Group

The English Opera Group collection forms part of the Britten Pears Arts Archive which documents the lives and work of Britten and Pears, as well as…