During recent times when catching up on reading has been a viable option for many of us, find out how Britten and Pears’ unique and beautiful bookplate came to be made.

Britten and Pears were incorrigible bibliophiles. Like many booklovers, they were eager to declare ownership of their collection, to have a personalised Ex Libris. And so early in 1970 Britten contacted long-standing friend and artist Reynolds Stone with a special commission.

The composer’s former assistant Rosamund Strode once mentioned that for a number of years it had been Britten and Pears’ intention to have a personalised bookplate made for them. The approach of Pears’ sixtieth birthday finally prompted Britten to act decisively.

‘Yes of course I will have a go at a combined book-plate for Peter and yourself’ Stone wrote to Britten toward the end of April 1970. His letter also disclosed some of the secrecy of the project. Britten obviously wanted it to be a surprise so a visit that Pears was planning to make to the Stone family home at Litton Cheney in Dorset the following month was met by the assurance that if he did turn up ‘I will of course hide any evidence of what I’m up to.’

The friendship that Stone and his photographer wife Janet forged with Britten and Pears can be traced to the mid-1940s. Both couples met through John and Myfanwy Piper. The Pipers also facilitated friendships between the Stones and other well-known names such as Osbert Lancaster, John Betjeman and Kenneth Clark—the last of whom became an Aldeburgh Festival identity. Britten and Pears, hosted Reynolds, Janet and their children during their visits to Aldeburgh. And, as Stone’s letter clearly suggests, Britten and Pears received similar hospitality on their trips to Dorset.

After reading history at Cambridge Stone became a trainee at Cambridge University Press. Work with Eric Gill honed his interest in wood engraving, which became his key medium although his versatility also extended to painting. A number of his designs incorporate an atmosphere of pastoralism or myth and folklore (such as those that accompany Britten’s five settings of Walter de la Mare’s verse in the score Tit for Tat). Stone’s style captures something of the tradition of Samuel Palmer and also the influence, especially of symbolism, seen in the work of one of the artists Britten and Pears most admired, William Blake.

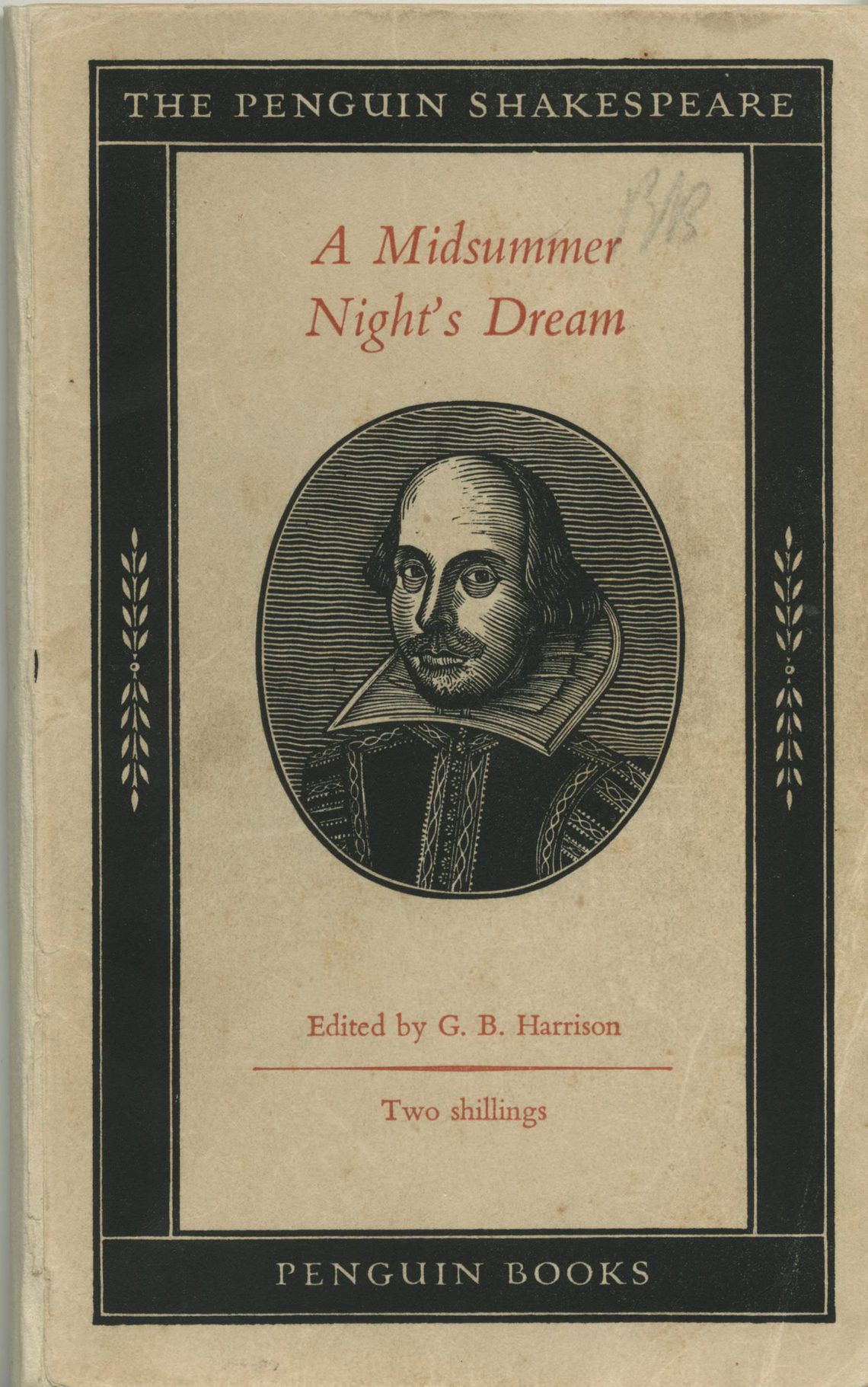

His work has featured in a wide array of formats: from coats of arms (including those of royalty), to pound notes, to book covers (the portrait on the Penguin edition of Shakespeare’s works is his), to lapidary inscriptions. He designed the cover and wood engraving illustrations for the 1958 and 1959 Aldeburgh Festival programme books. His designs are familiar, even if his name may not be.

Britten’s annotated copy of the Penguin edition of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, with Stone’s engraved portrait of Shakespeare.

After Britten’s initial approach to design a bookplate Stone made rapid progress on the commission, coming up with an attractive stamp whose beauty relied on simplicity and symbolism combined. Like most perfectionists, however, he could be self-critical when it came to finalising his work. On the 3 June 1970 he confessed:

Dear Ben

I enclose proofs of a trial engraving. You will probably dismiss one of the Pears. In any case I’ve muffed one tree here shown. But I could re-do it making it clearer and one name area smaller. The names of course are the important thing and either one of the proofs could do I think, and could be painted if you like in colour or colours.

Yours Reynolds

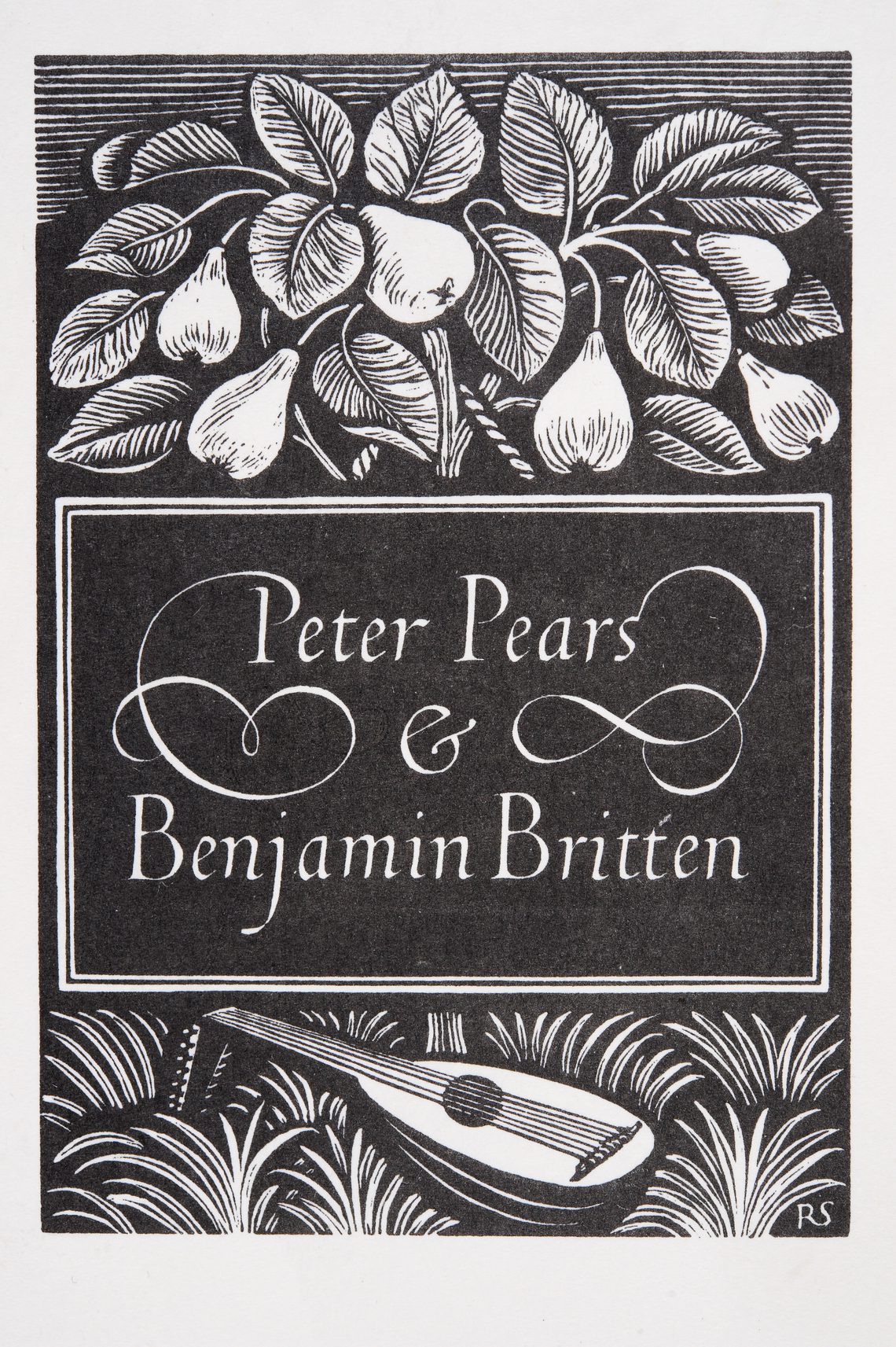

In the finished plate the sequence that we are used to seeing—of ‘Britten–Pears’ is reversed in the ‘name area’, emphasising that this was the composer’s gift. Britten the music maker is represented by a lute in the lower half of the design whereas a visual pun on Pears’ surname dominates the upper half—and may also be a passing reference to the singer’s interest in gardening, particularly the orchard situated behind the Library at The Red House.

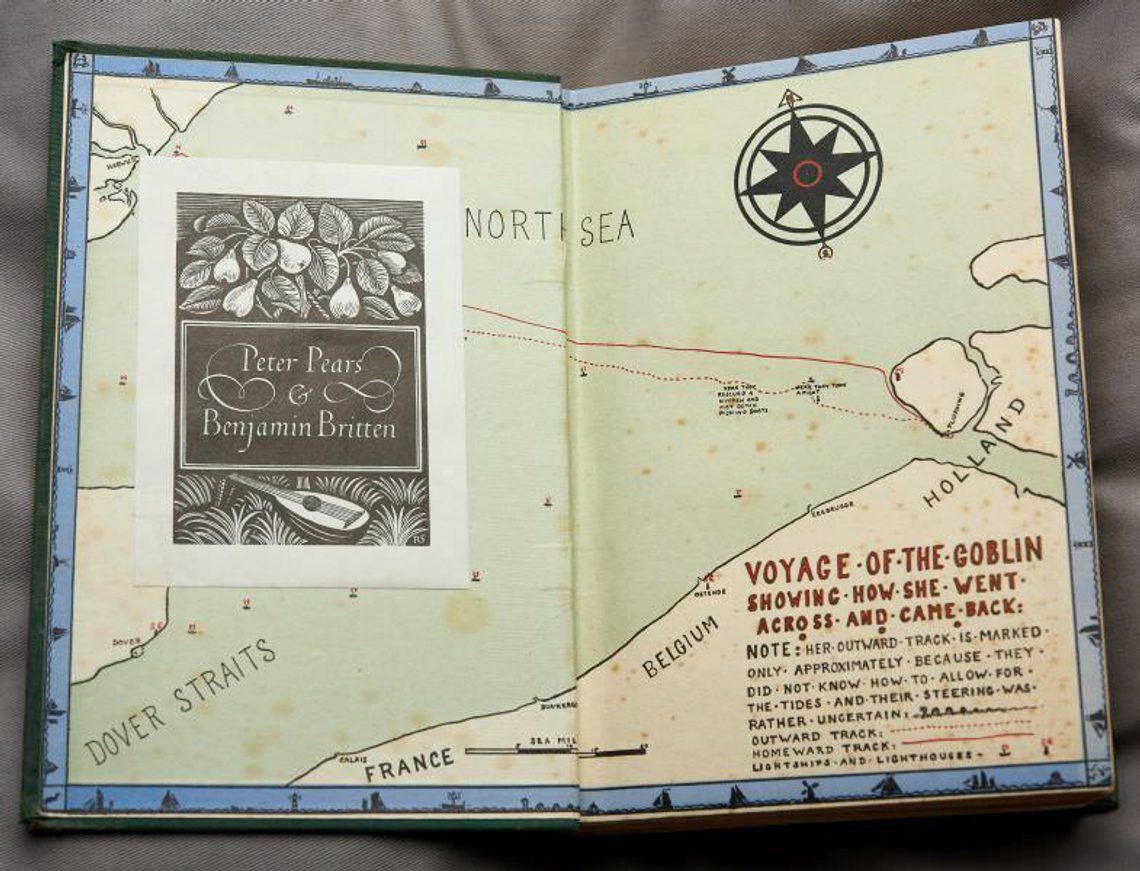

Reynolds Stone’s bookplate for Peter Pears and Benjamin Britten, 1970

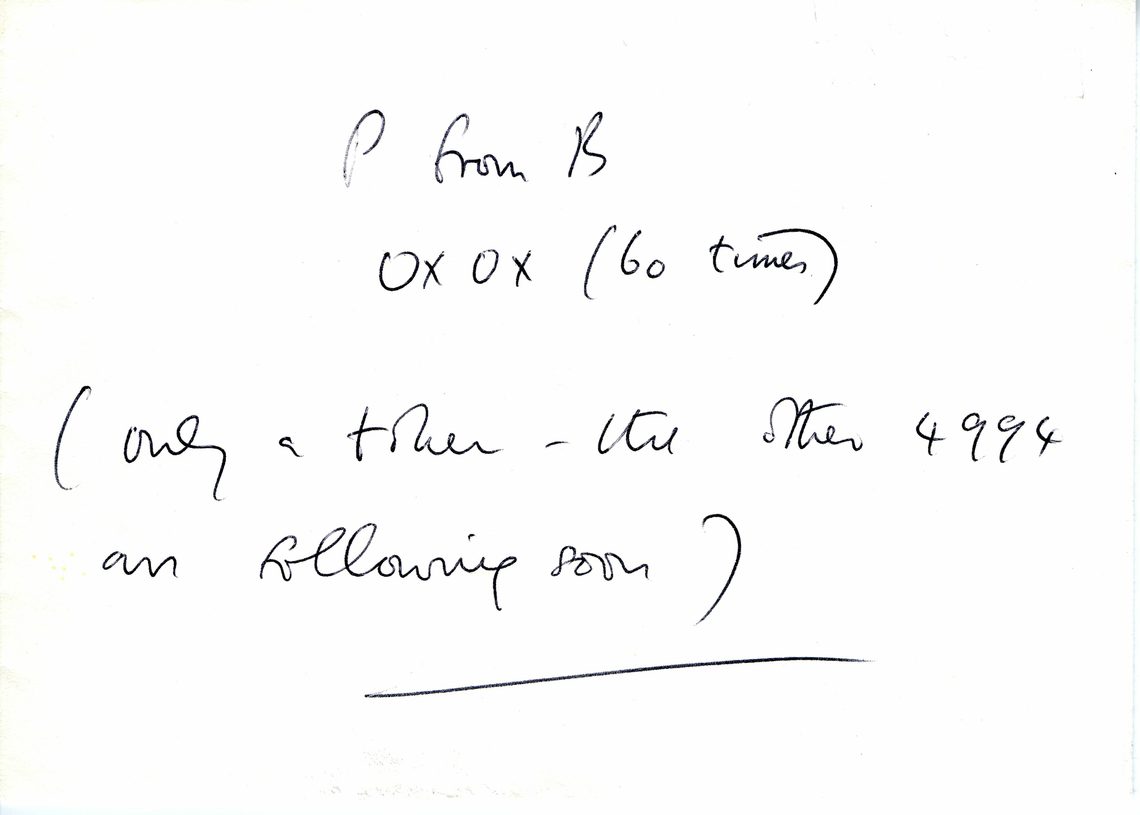

The plate was printed in black and white (as shown in the illustration above), sepia and white, and lime and white. A now familiar sight to Library visitors, six relatively fresh copies of the plate made their appearance on the 22 June 1970, Pears’ birthday, with a card that read

P from B

OXOX (60 times)

(Only a token – the other 4994

Are following soon)

The remaining set followed on the 13 September when Stone wrote:

Dear Ben

The book-plates are in their way (addressed to Peter) posted last Friday morning. The parcel post is awfully slow I fear. One caveat please have them kept in a dry place because of the glue which will otherwise make them stick together! (13 September, 1970)

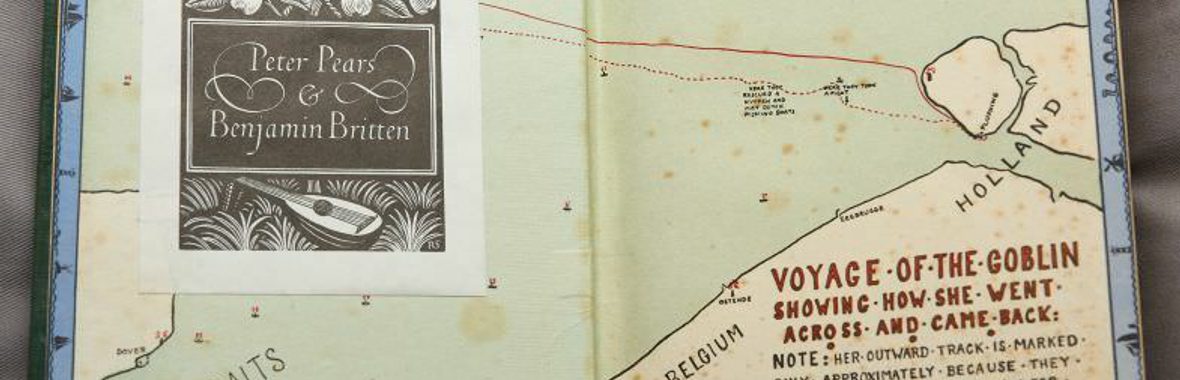

The bookplate in Britten’s copy of Arthur Ransome’s We Didn’t Mean to go to Sea

- Dr Nicholas Clark, Librarian