Archive Treasures: “Once-played-badminton-for-Suffolkship” – Stephen Potter at the Red House

StoriesBooks tell us about their readers: who can resist peering at someone’s bookshelves? Every book collection is a map of the owner’s interests – and for the owner not merely a map but a timeline, since he or she may well be able to remember when and where the book was acquired and read, and what effects it may have had on them. The books in Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears’ collection tell many stories: the most famous is the second-hand copy of George Crabbe’s poems, found in California, that triggered the composition of Peter Grimes, but many other stories sit on the shelves. Two slim volumes in the Red House tell a story of Britten and Pears’ first years in Aldeburgh, the start of one relationship that was lifelong and another that was cut off.

Britten and Pears moved to Aldeburgh in 1947, leaving the Old Mill in Snape for Crag House on the Aldeburgh sea-front and from here, the following year, organising the first Aldeburgh Festival. A little later, in 1951, another couple arrived in the town: artist Mary Potter and her husband Stephen, who bought the Red House on the edge of town. Mary Potter is a familiar figure in Britten and Pears’ story: her paintings are well represented in the two men’s art collection (and many, from the Red House and elsewhere, can be seen on the ArtUK website). Her husband Stephen is a much more elusive figure, present in Britten and Pears’ story only in the opening years of the 1950s, but the two books tell us about their relationship with him and, perhaps, where that might have gone if circumstances had been different.

Stephen Potter, from his obituary in The Times

Stephen Potter (1900-1969) began his career as an academic, lecturing on English Literature, but moved to work for the BBC and, after the Second World War, to a career as a freelance writer in a range of fields. His most famous work came about something by accident: when power shortages in the hard Austerity winter of 1947 meant that the BBC had to stop broadcasting for ten days, Potter filled the time by dashing off a book.

The Theory and Practice of Gamesmanship – or, as it is better known, simply Gamesmanship – sets out its remit in the subtitle: The Art of Winning Games without Actually Cheating. In a pseudo-academic style, Potter sets out the ways in which an average player can defeat someone better than them, through subtle psychological warfare: ways in which the better player’s concentration and focus can be diminished and a general sense of unease, distraction and irritation created.

Gamesmanship: the title page.

(For example, when playing golf or any other sport that requires concentration and stillness, offer your opponent a lift to the venue and then make it seem a race against time to get there, raising their pulse rate; for sports involving adrenalin, of course, this may be counterproductive.) A whole terminology is drawn up, of gambits, counters, “hampers” (things that obstruct one’s opponent), “parlettes” (short pieces of dialogue to be memorised and deployed) and so forth. The book was a great success and in a series of sequels (Lifemanship, One-Upmanship and Supermanship) Potter widened the concept to life as a whole, depicting social interaction as a matter of masked competition, the infliction of subtle embarrassments, and a constant struggle for status.

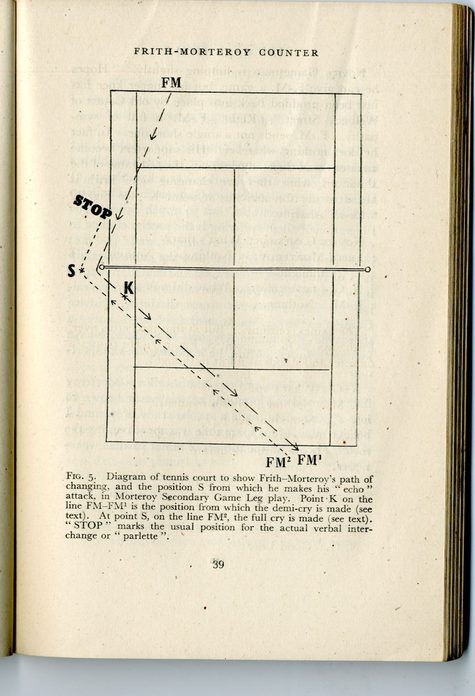

Diagram of a tennis court, from Gamesmanship, showing the precise point at which, during a change of ends, a Gamesman should hint that he has a secret heart condition.

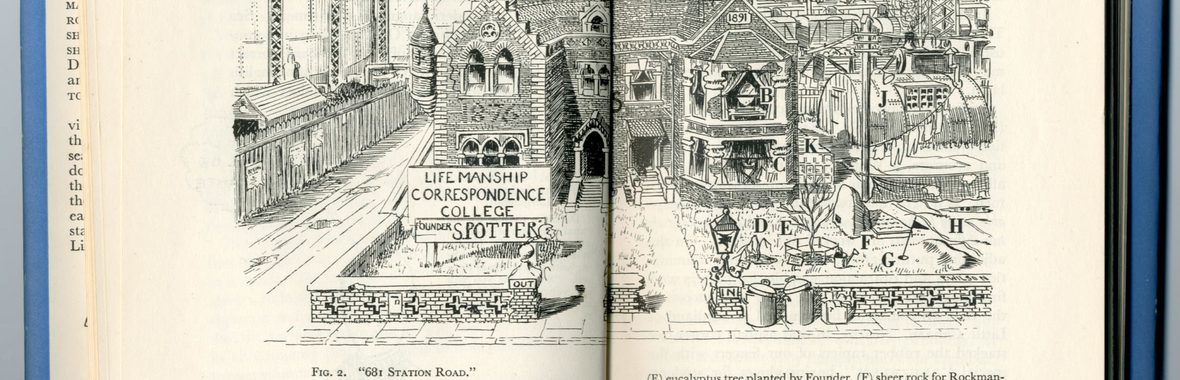

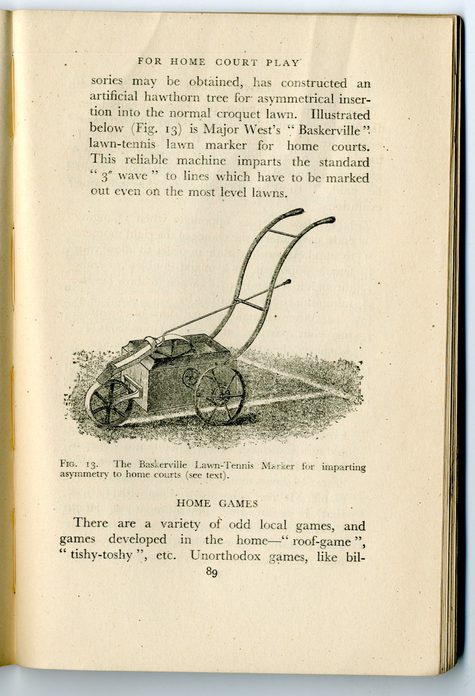

Potter was an obsessive games player and drew on his own experience, recast, for the books. A motif that occurs a couple of times is the home tennis court: speaking in Gamesmanship of the very earliest days of the concept, Potter talks about games of tennis in the 1920s “at the Farjoens’ house near Forest Hill, where Farjoen had wrought such havoc among so many visitors, by his careful construction of a “home court”, by the use he made of the net with the unilateral sag, or with a back line at the hawthorn end so nearly, yet not exactly, six inches wider than the back line at the sticky end.” Later in the book he indicates the way that gamesmanship has become an exact science with an illustration of a machine for marking up a lawn tennis court so that all lines have “the standard 3” wave”, even on the most level turf, while in One-Upmanship the illustration near the start of the Lifemanship Correspondence College now supposed to be operating in Yeovil shows, in the garden, a shambolic tennis court labelled “Vicarage type”.

Machinery for producing the perfect off-putting tennis court, from Gamesmanship.

All of the ploys he describes here, of course, could have been applied at the Red House: the tennis court here hosted games between the Potters and their friends, including Britten and Pears.

A tennis party at the Red House, mid 1950s, including Britten, Mary Potter and Laurens van der Post (photographer unknown)

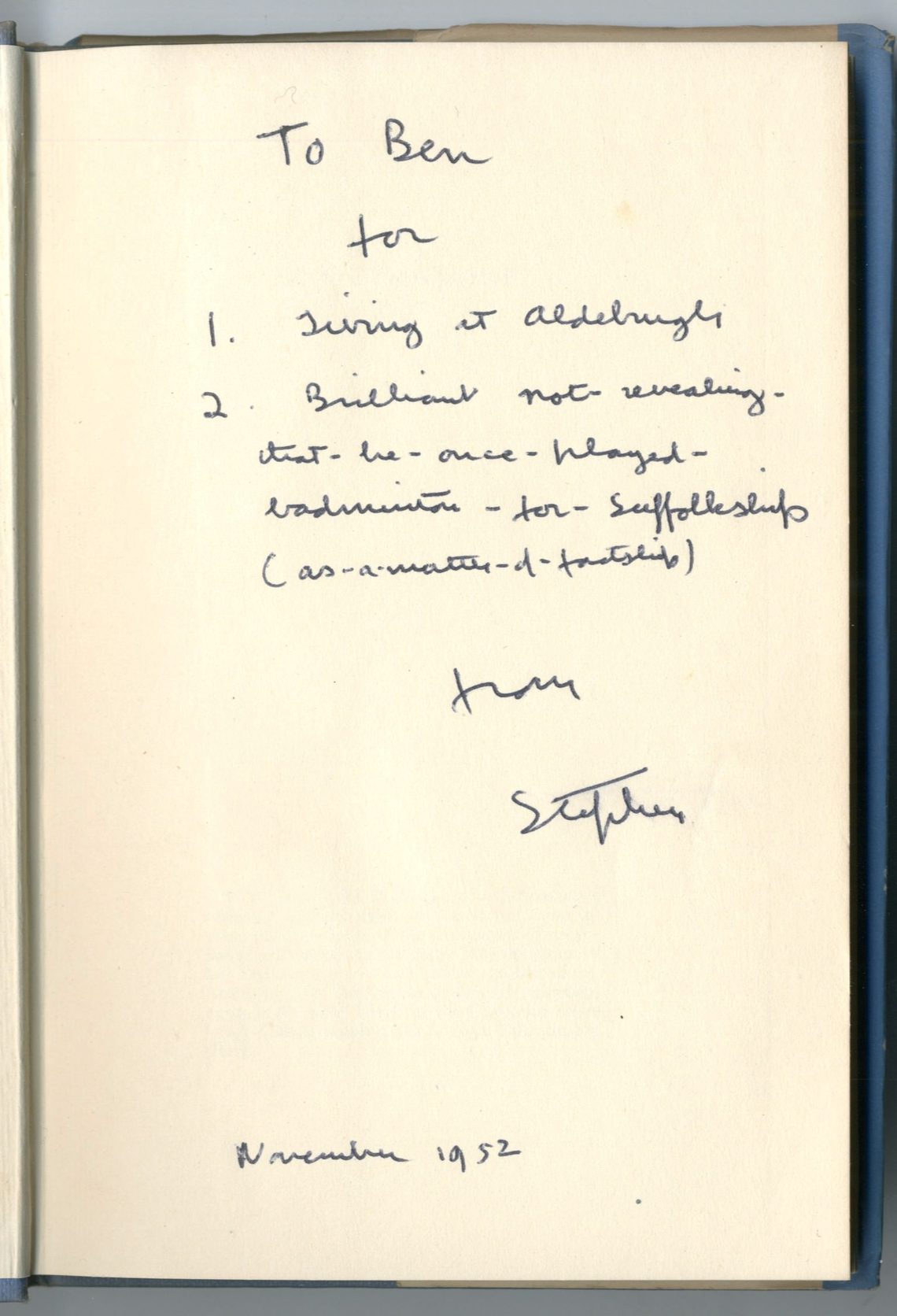

Potter’s friends found their way into his work: for example, the philosopher and public intellectual C.E.M. Joad, a colleague at Birkbeck College, is said to have been Potter’s tennis partner at a crucial moment in the development of gamesmanship (when two younger and better players were unsettled by a suggestion that they had been unsportsmanlike, and lost). The copy of One-Upmanship at the Red House admits Britten to this circle: Potter’s inscription inside the cover ascribes a ploy to Britten, saluting his “Brilliant not-revealing-that-he-once-played-badminton-for-Suffolkship (as-a-matter-of-factship)”. The opening of the book, too, nods to the Potter’s new home and new friends: the first chapter purports to be a speech given by Potter as founder of the discipline, in which he notes that the expanding discipline of “Lifemanship throws its lifeline from Alaska in the West to Colchester in the East” but then adds, in a footnote, that “a happy and natural result of the Aldeburgh Festival has been the founding of a small Lifemanship Club in that resort”. The notes on birdwatching later in the volume, “Bearded Titmanship”, take their name from a bird to be found in the local reedbeds. All seemed set at this stage for the linkage of Potter with Britten, Pears and Suffolk to continue and to feed into future books.

Presentation inscription in Britten’s copy of One-Upmanship.

The association was a brief one, however: in 1954 Potter asked his wife for a divorce and moved out of the Red House. (His second wife ran a marriage bureau; on the evidence of this instance, she knew her stuff.) Britten and Pears took the side of Mary Potter in the breakdown: their friendship with her was lifelong, encompassing their exchanging houses with her when she found the Red House was now too big for her, but Stephen no longer formed part of their lives. We are left to wonder how Britten might have figured in future books, picking up on hints in the existing ones. The Two-Club Forcing Approach, for example, in which a gentleman should belong to two clubs with radically different demographics, and unsettle the members by consistently turning up at one while dressed for the other, is tailor-made for Britten and Pears’ combination of artistic bohemianism with extreme tweed-clad respectability. The description of how Carmanship, and the Placid Salutation of other road users, allows one to drive at reckless speeds and get away with it was made for Britten’s motoring habits, too. Alas, we never got a full analysis of Composership: and, of course, the stress that Lifemanship would have placed on the maestro unsettling and dominating his orchestra and audience would have been very much against Britten’s ethos. Still, for one brief moment in the early fifties these two worlds intersected, and the presentation inscription in one of the Red House books is there to mark that for us.

- Dr Christopher Hilton, Head of Archive and Library