Our archive preserves thousands of Britten’s music manuscripts from his juvenilia – his earliest notes written from the age of five – to his unfinished Praise We Great Men. Numerous treasures from every stage of the composition process – from first sketches to published editions. However, the full score fair copy of Britten’s Piano Concerto is a music manuscript with a particularly interesting story. This is the neat final version of the work, in ink in Britten’s hand, sent to the publishers ready for publication.

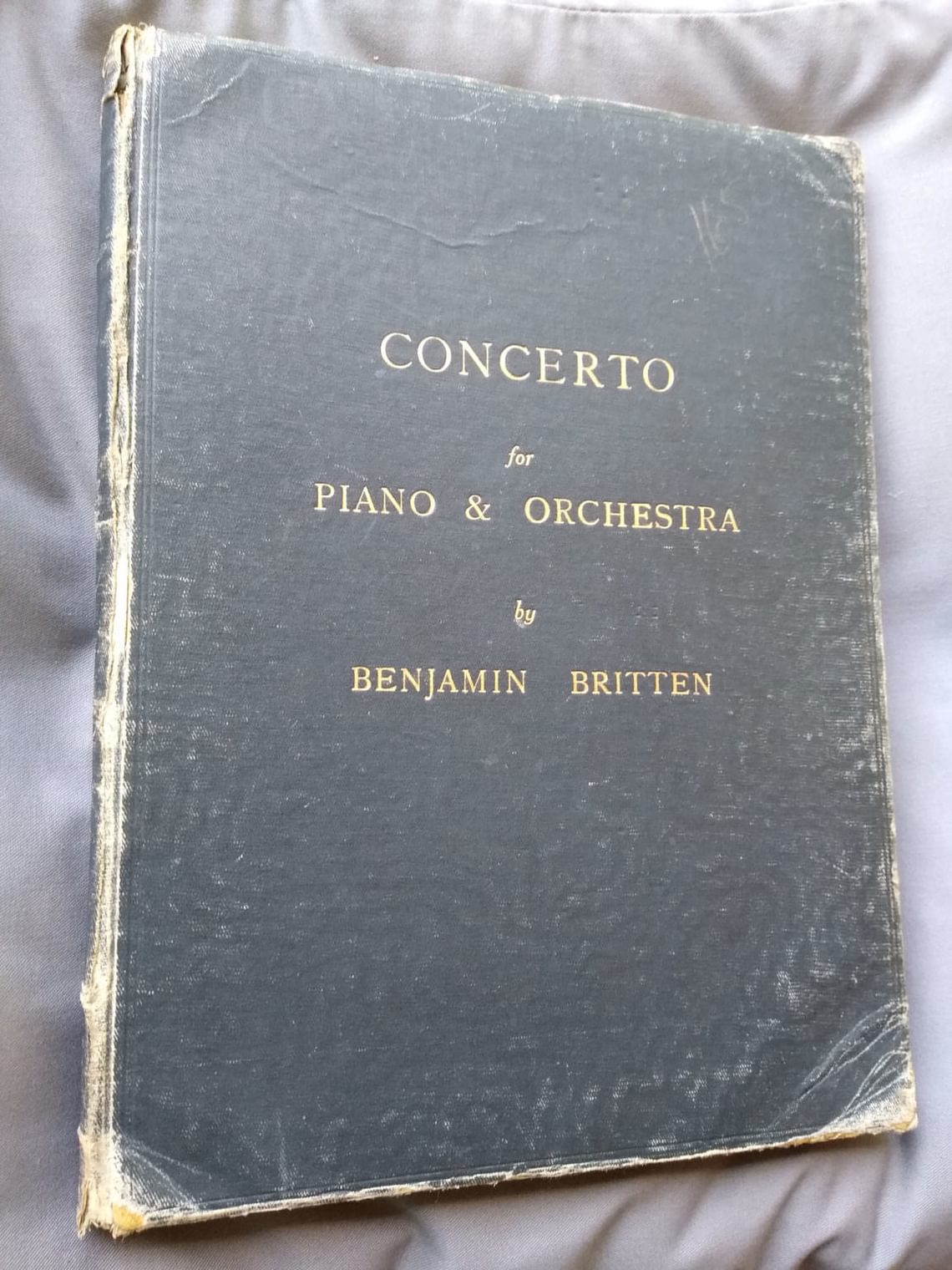

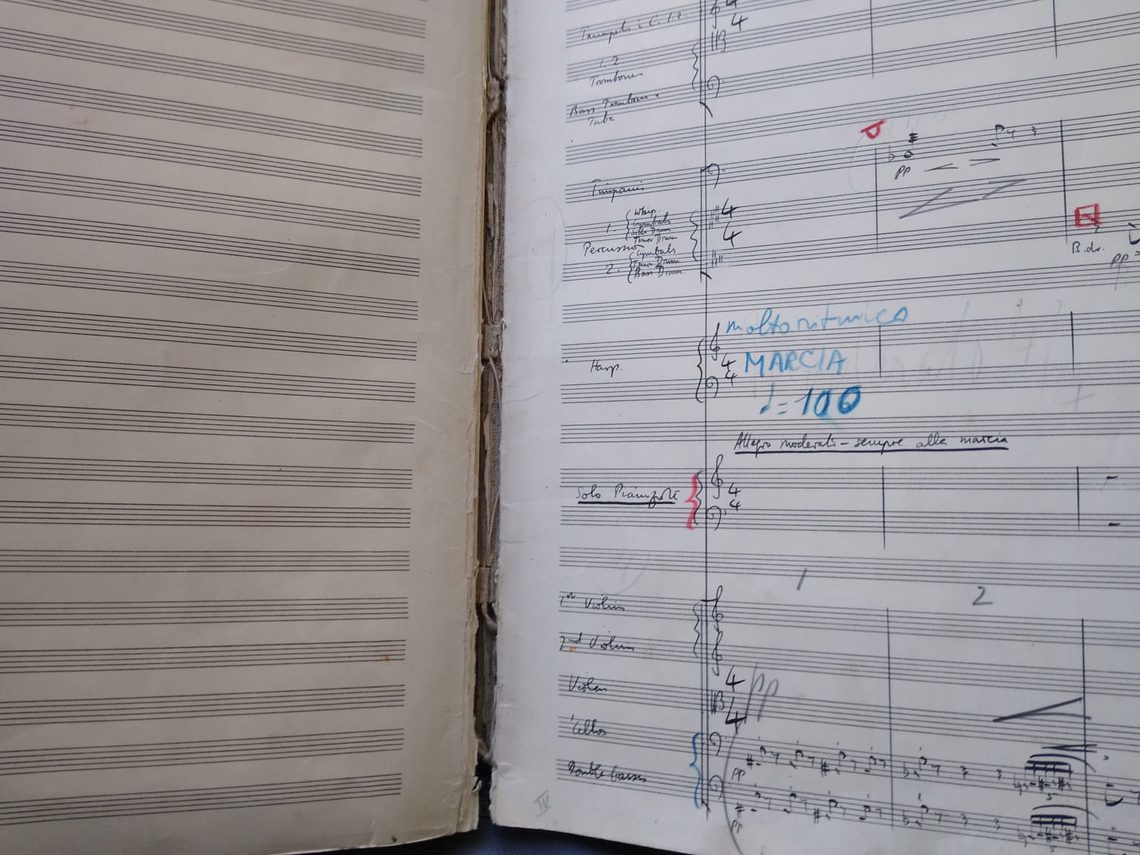

The bound music manuscript for Britten’s Piano Concerto.

Britten had already begun work on his Piano Concerto when, at the beginning of April 1938, he moved into the Old Mill at Snape, sharing the accommodation with his good friend and fellow composer Lennox Berkeley. Britten dedicated this work to Berkeley. Had he planned a second Piano Concerto? – this one was first performed and published as ‘No.1’ but a successor was never composed.

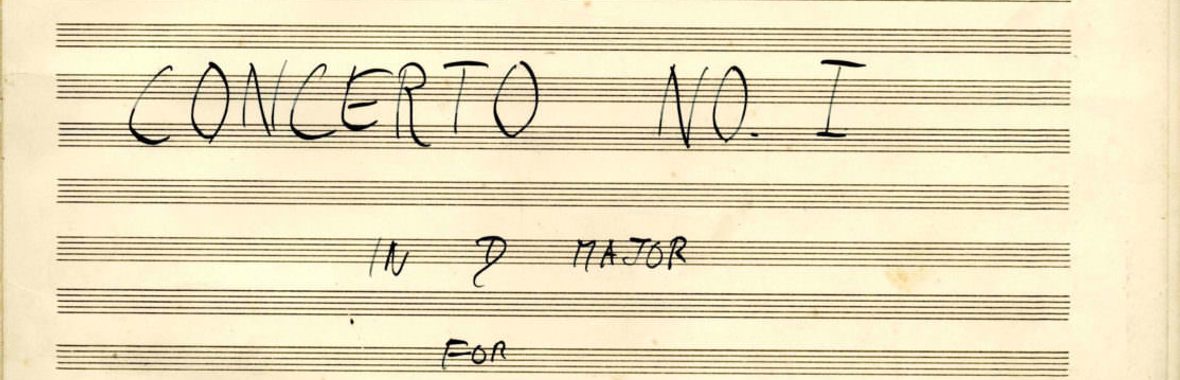

Title page with Boosey and Hawkes hire library stamp.

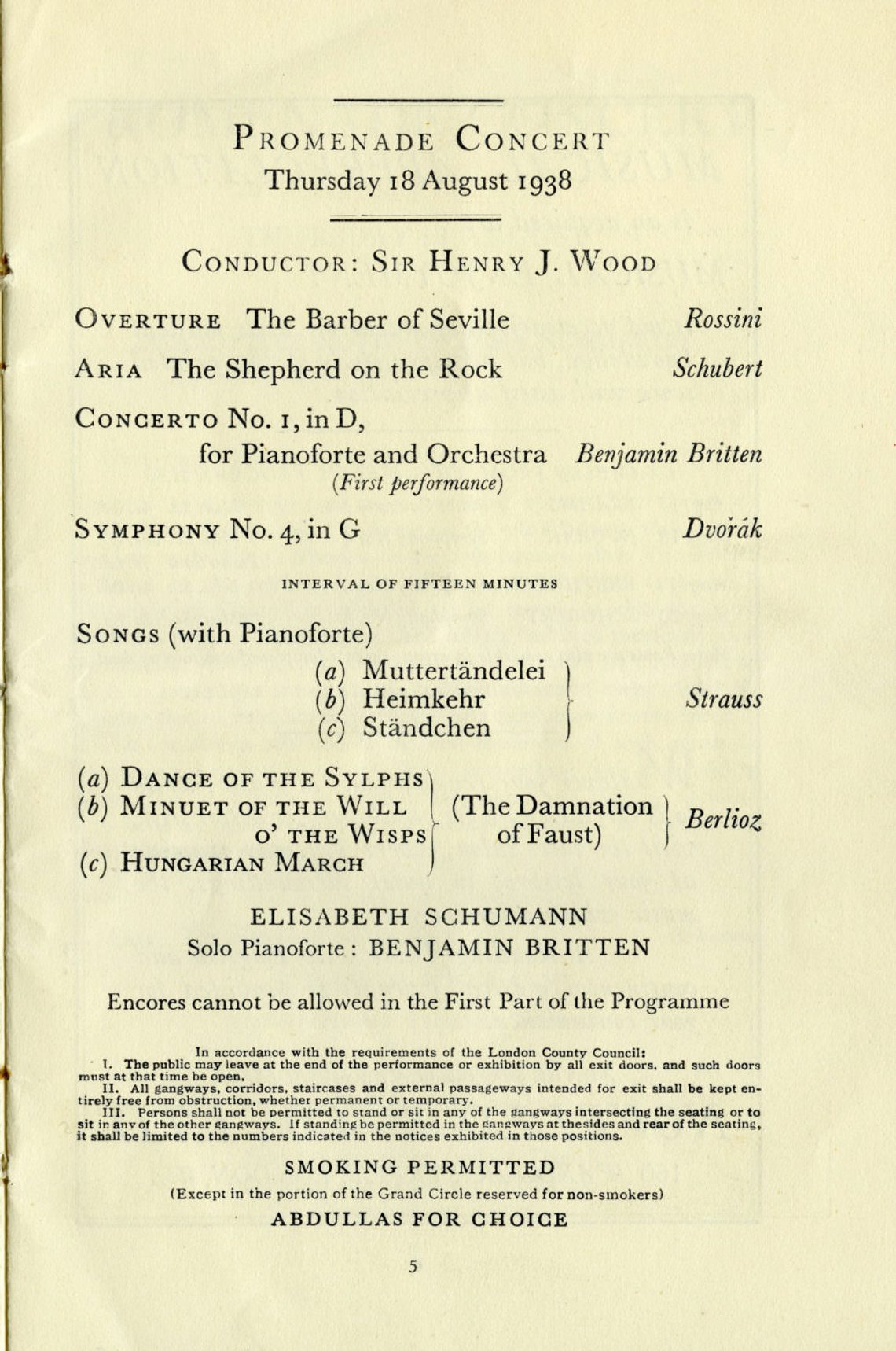

Britten completed the work on 26 July 1938 just before the first rehearsal on 5 August for it’s premiere two weeks later at London’s Queen’s Hall as part of the BBC Proms Concerts. Britten played the challenging solo piano part with Henry Wood conducting. Britten wrote to his publisher Ralph Hawkes that the first rehearsal had gone well – ‘The piano part wasn’t as impossible to play as I had feared, & with a little practice this week ought to be OK’.

Programme for the work’s first performance.

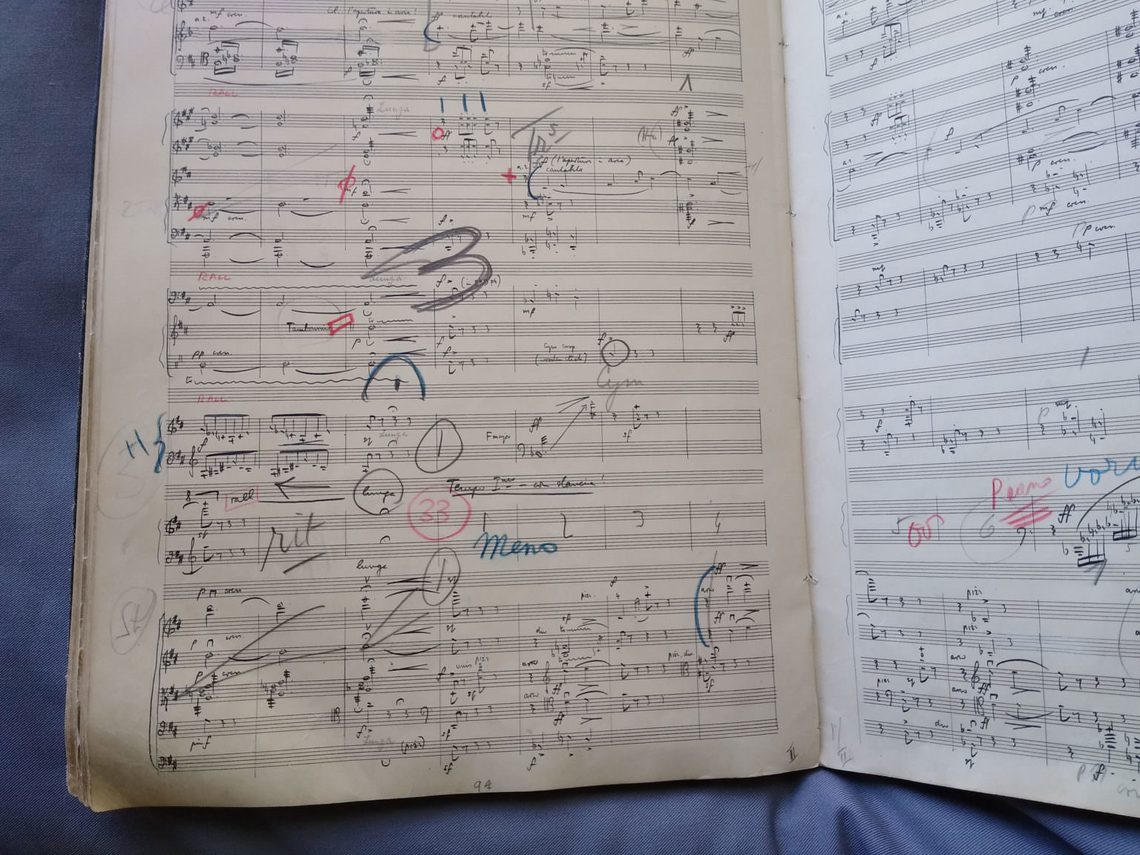

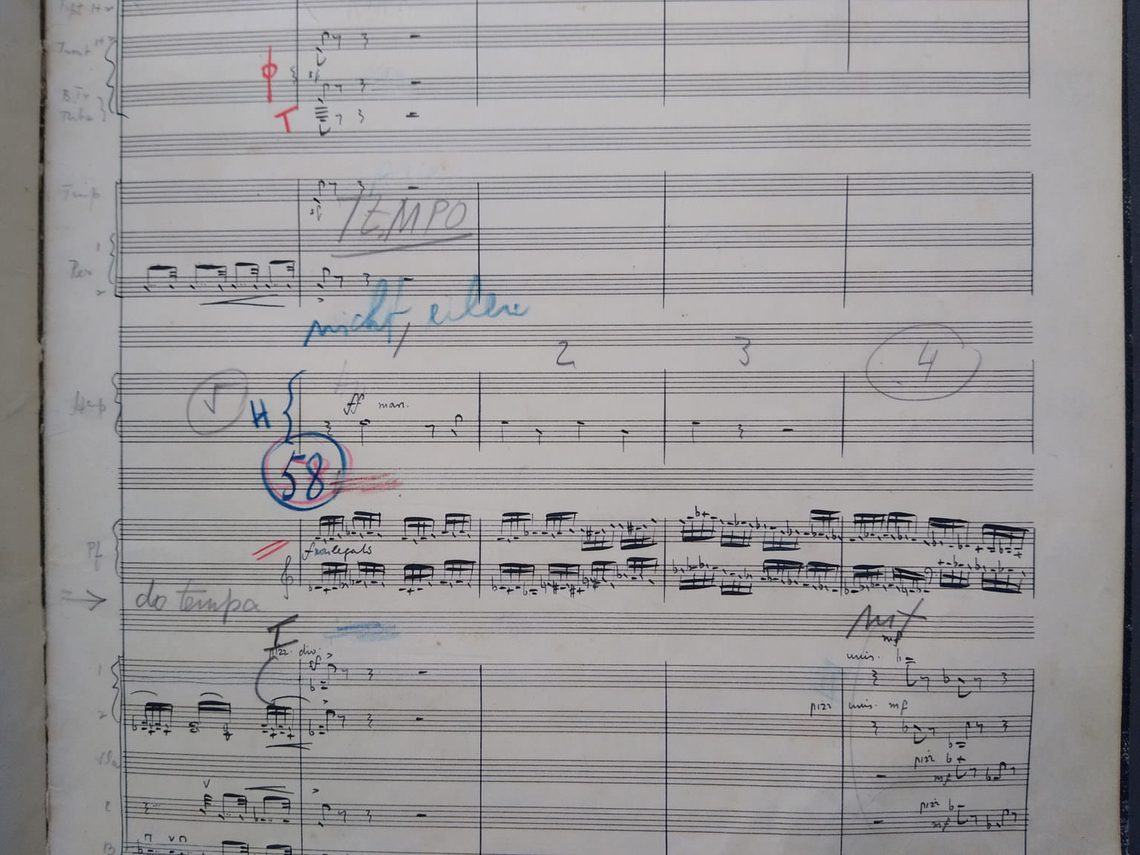

As the work was not yet published, Wood used this bound music manuscript to conduct the first performance and made annotations as aide-mémoires on the pages during rehearsals. The manuscript, stamped ‘Boosey and Hawkes Ltd Hire Library’ on several pages, was hired out for further performances following the premiere. We have programmes for two of these in our archive – Adrian Boult conducted the BBC Orchestra on 16 Dec 1938 and Serge Krish the New Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra on the 12 Feb 1939 with Britten at the piano for both concerts. The music manuscript bears many annotations made by a number of different conductors who hired it and intriguingly some conducting marks in blue pencil are in German. These annotations reveal a great deal about different interpretations of the work.

Annotations made by conductors using the manuscript.

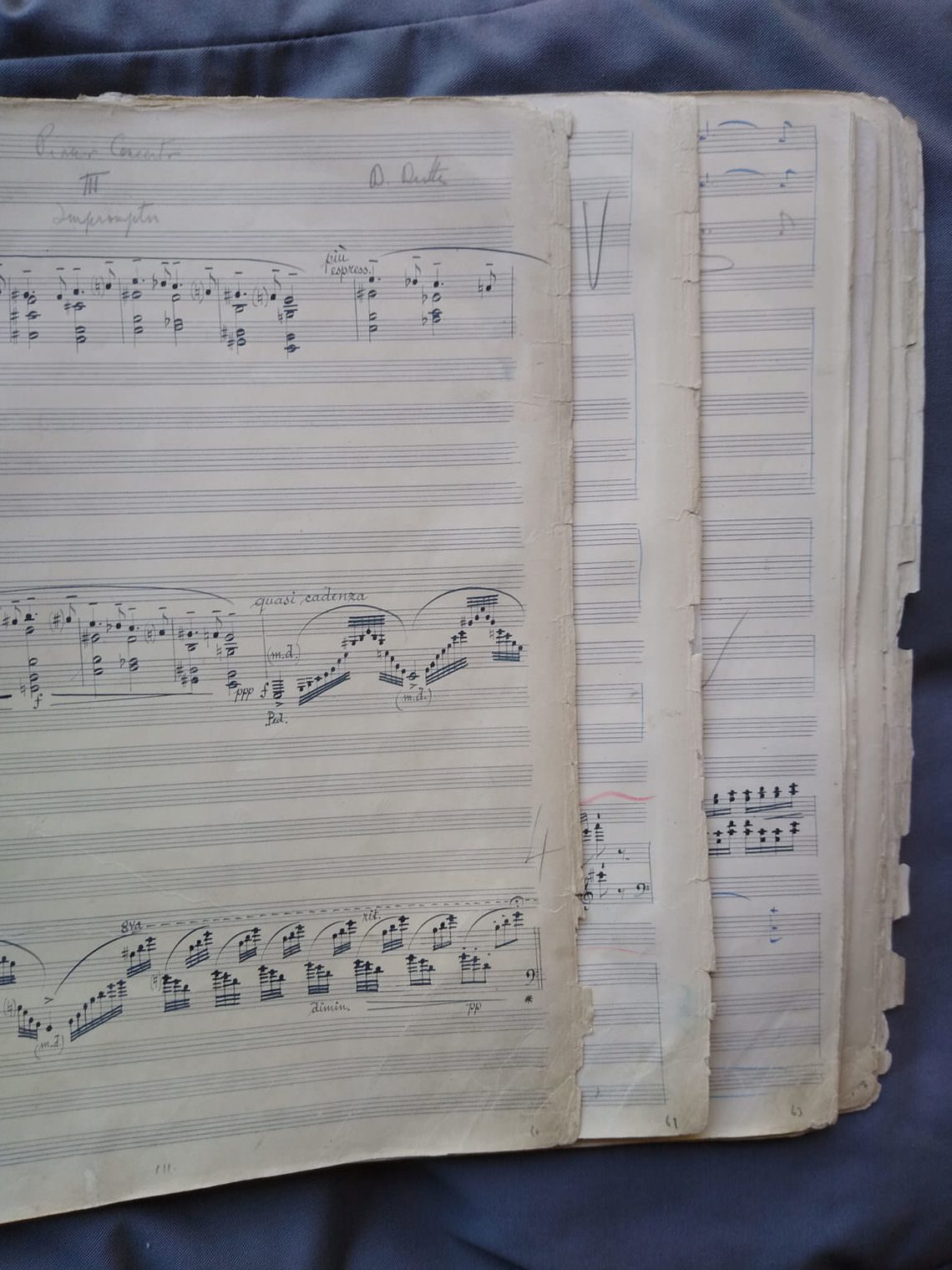

In 1945 Britten revised the original slow third movement, described as Recitative and Aria in the original version, replacing it with the ‘Impromptu’. The original third movement was torn out of the bound music manuscript, breaking the binding, and the pages of the new movement loosely inserted in its place. These new pages stuck out becoming folded and torn along their edges as the volume continued to be hired out by Boosey and Hawkes for performances. The volume was no doubt looking well used by now.

The volume’s broken binding at the place between the 3rd and 4th movements.

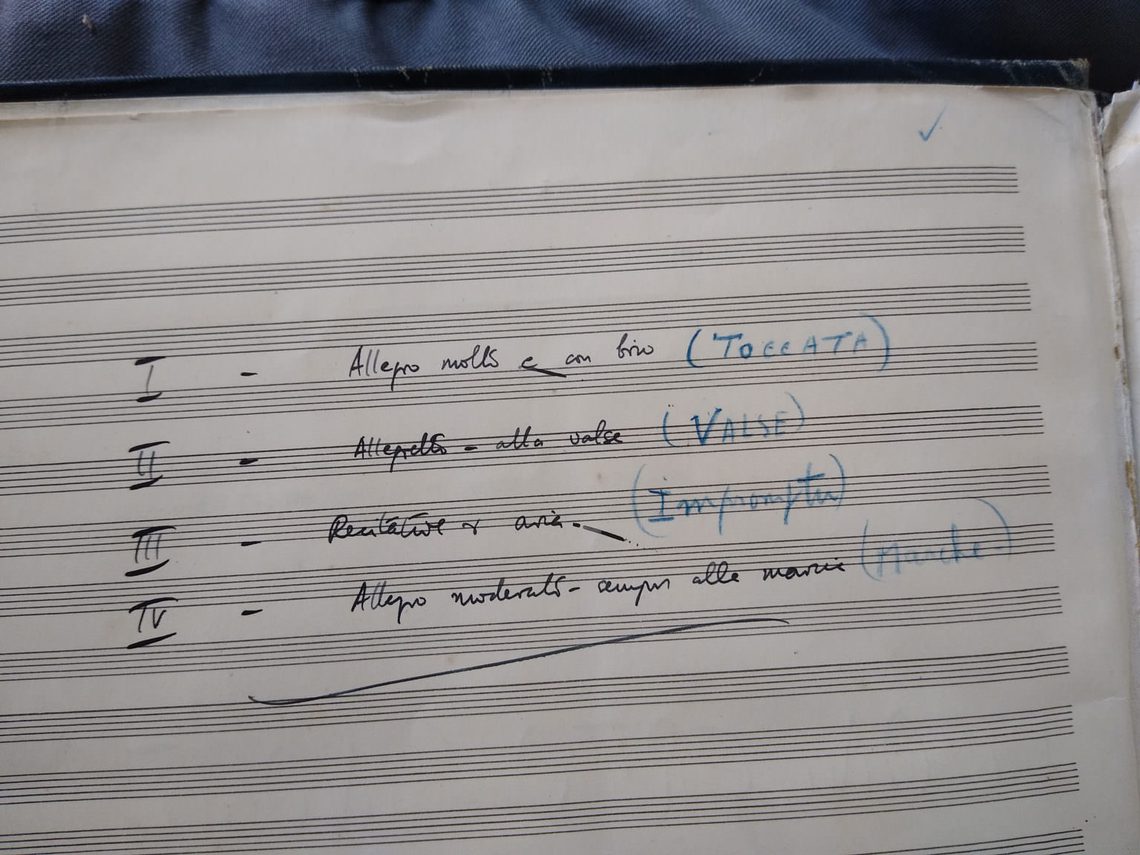

The first performance of the revised version was given on 2nd July 1946 at Cheltenham Festival – this time with Britten himself conducting and Noel Mewton-Wood at the piano. The music manuscript therefore also bears Britten’s own sparse conducting marks, mostly bar counts. Britten renamed each movement – the conductor with the blue pencil writing the new names on the manuscript.

The movements were renamed in the new version.

Britten’s own conducting marks.

Once the work was published this volume could thankfully rest but it was in a very poor state, with broken binding, damaged spine, pages with torn edges and dog-eared and grimy corners where many conductors had turned the pages. The volume was so bad that we could not bring it out of the strong room without risk of causing further damage. It was therefore conserved with work being carried out to make the volume and its pages stable so that it could be handled again but being careful not to cover up the damage which tells so many stories about its use. We certainly didn’t want the volume to look new after its conservation work! The spine was reattached but the binding left broken. The damaged edges to the loose pages were repaired with tissue adhered with wheat starch paste but the wear and tear can still be seen. The page corners still show the dirt from many conductors’ fingers. The conservator found fragments of tobacco between the pages; presumably a conductor had rolled a cigarette or lit a pipe whilst studying the score!

Loose pages of the new 3rd movement, in the hand of copyist Brian Easdale, with edges stabilised and repaired.

Thankfully this volume is now carefully preserved in our strong room but it still bears the marks which tell us its interesting history.

- Judith Ratcliffe, Archivist