The archive at The Red House spans all aspects of Britten and Pears’ lives together – from their professional activities, the compositions and performances that made them world famous, to the everyday details of their household here. Every scrap of paper tells a story – and they kept virtually everything.

The story of their long relationship, the years in which the two men maintained what was effectively a long and fulfilling marriage despite the laws against homosexuality, is woven through the archive – in the letters they exchanged, the photographs of them together, and in the covert and not-so-covert announcements woven into Britten’s music. Their financial documentation is perhaps the one area one might think too dry for such an emotional topic. Even here, however, the story of the two men’s lives together is vividly present.

As self-employed artists, Britten and Pears had to compile tax returns at the end of the financial year; these would summarise what had been earned, what had been spent, and what expenses were work-related and thus different for tax purposes. And these returns were liable to be audited; evidence had to be kept that would back up any statement they made to the tax authorities. For this reason detailed receipts were kept for all their purchases. After seven years had elapsed, the possibility of an audit had gone and in theory the receipts could be discarded; this seems to have happened a little in the early years of their time in Aldeburgh (life at their first house, on Crag Path, is less well-documented) but once they moved to the large rambling Red House, with its copious storage space, the incentive to carry out records management was gone and almost everything survived.

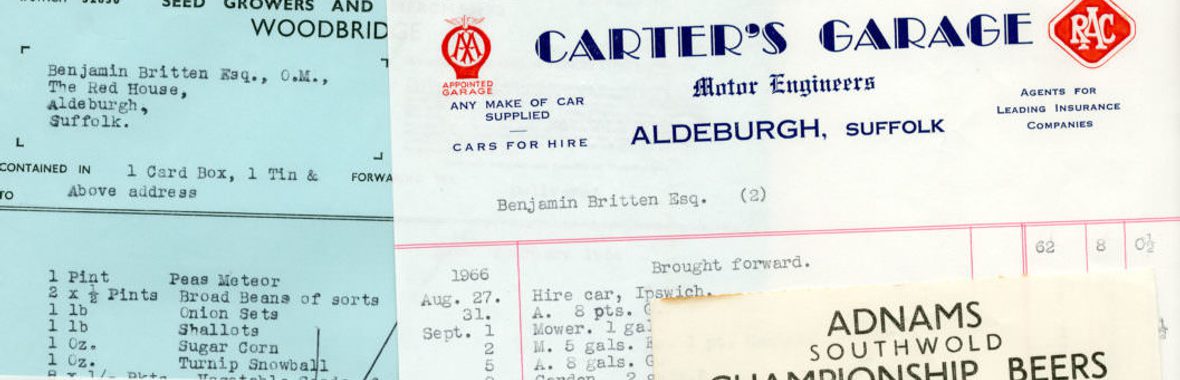

A selection of receipts from the Archive (BBF_1966_selected_montage)

The receipts, catalogued recently by a team of volunteers, are now described on our online catalogue and can be seen at https://www.bpacatalogue.org/archive/BBF-2. They tell us about Britten and Pears’ lives together – what they ate, what they planted in the garden, where they had their cars serviced. The social history of shopping is laid out in them: when they move to Aldeburgh many shops allow customers an account on which they accumulate items and which is settled at the end of the month, a means of payment now superseded by the monthly credit card bill, and many shops still deliver in a way that conjures up the Victorian butcher’s boy on his bicycle. They tell a story about Aldeburgh as a town, too: how the High Street evolved over time, with some shops remaining and others vanishing from the scene, how once there was a garage on the High Street while now there is nowhere closer than Snape to buy petrol. And also, in surprising ways, they shed light on their relationship in the years that this was illegal, as we see in the little piece of paper that is the subject of today’s article, a 1966 clothes shop receipt.

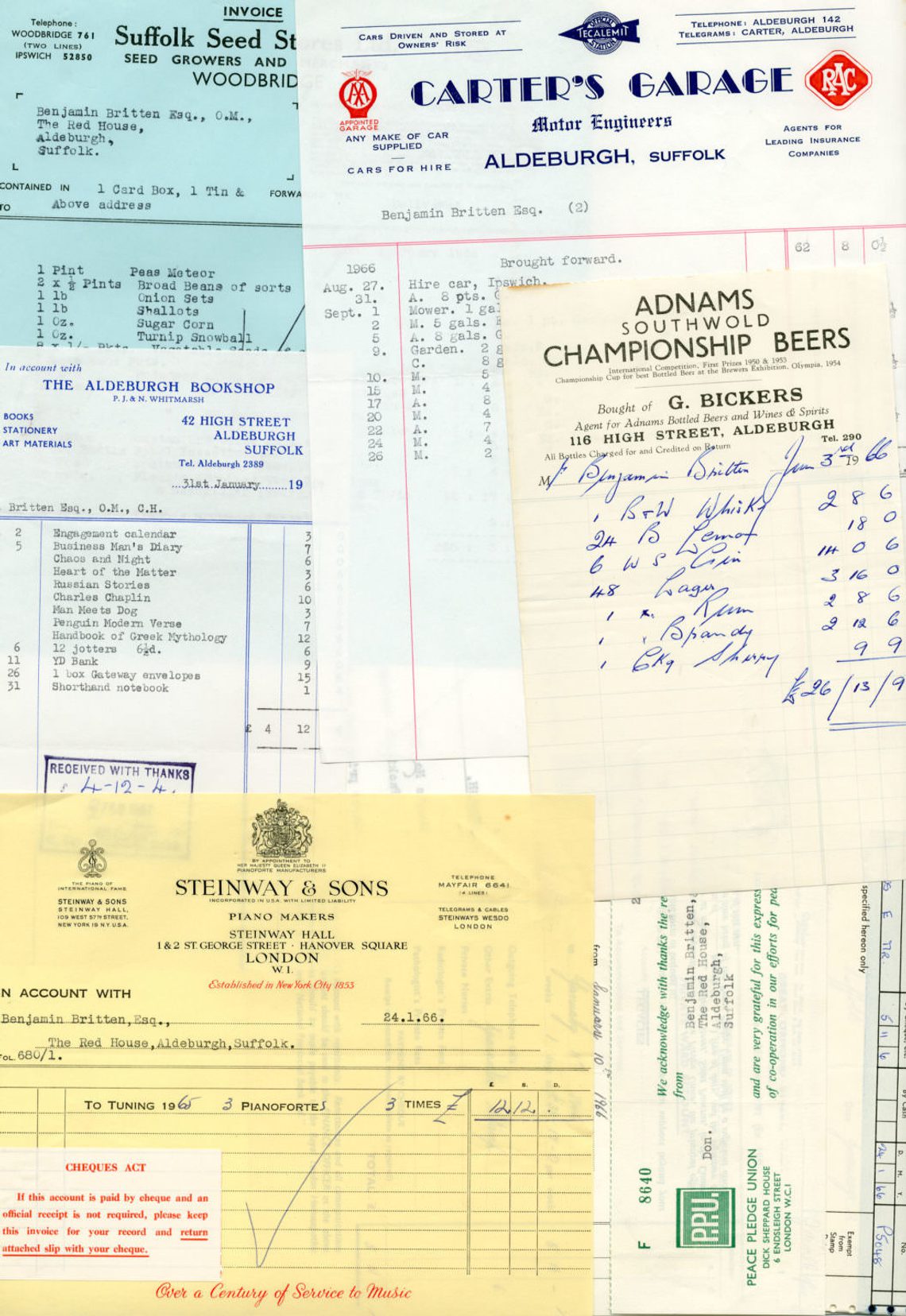

A receipt from O & C Butcher (BBF_1966_001_Butcher)

Until the Sexual Offences Act of 1967 effected the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality, Britten and Pears lived every day with the threat of exposure and penalty. The fact that they formed a professional partnership was cover of a sort, of course, but it was necessary for them to make sure that they maintained plausible deniability about the emotional and sexual side of their relationship and their natures: to avoid giving too explicit indications that this was more than a professional association. For this reason, Britten and Pears never had a joint bank account, and never held property in common. We see them carefully reimbursing the other for expenses incurred; we even see them paying the other for food and lodging, calculating how long they had spent at “Britten’s property” in Aldeburgh and how long at “Pears’ property” (a sequence of London bases) with money transferred between their accounts to settle this up.

In early 1966, still over a year before Britten and Pears’ relationship was made legal, Britten settled up his bill with O & C Butcher – the clothes shop that still stands on Aldeburgh High Street – for transactions in late 1965. They are mostly mundane purchases – these receipts are a splendid way to bring home the ordinary humanity of famous figures, showing Britten buying socks and Viyella shirts. The one hint of a more glamorous lifestyle is the purchase of bow ties, presumably for performance. Right at the top of the receipt, however, half-hidden by the stamp affixed to show that the bill had been paid, is a single revealing line: “Shoe repairs (for Mr Pears) – 8/6”. That “for Mr Pears” speaks volumes. It shows us the two men keeping their expenses carefully separate: they knew that if they were audited, this piece of paper would be seen by figures in authority, and thus had to show them keeping their money apart. Distinguishing this one line with “for Mr Pears” indicates that this is an expense different from the others, one which Britten would reclaim from Pears, and one which the shop knew should be treated differently. It is an indication of the level of care that a gay couple had to take at this time, to avoid breaking cover. But the fact that the line is there at all, rather than Pears having his own separate bill, also tells a story, a more encouraging one – it clearly indicates that at some point in late 1965, Britten (or his representative) went into O & C Butcher to pick up Peter’s shoes, and that the shop happily put that item on Britten’s bill, knowing that despite the care taken to maintain official deniability, the two men were a couple. The lives the two men lead together involve care and subterfuge – but in a sense the town is in on the secret, happy to preserve the fiction, not to pry and to allow the two men their lives together. Of course none of this should ever have been necessary: but that single line documenting eight shillings and sixpence spent on shoe repairs shows perfectly the way that, in the face of official sanction, the two men made a secure and loving home together in a town that was happy to let them do that.

PH_04_0478

- Dr Christopher Hilton, Head of Archive and Library