What links the composer of the evocative TV theme for Brideshead Revisited to The Red House?

The composer Geoffrey Burgon may be best known for his work in television and cinema. Among his credits are the scores for Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979) and, by contrast, the haunting theme for the 1985 film Turtle Diary. His many TV credits include the BBC adaptation of C.S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia. Undoubtedly though, his themes for John Le Carré’s Tinker, Taylor, Soldier, Spy (1979) and the period drama Brideshead Revisited (1981), based on Evelyn Waugh’s novel, comprise some of his most popular and widely recognized music. Burgon’s overall repertoire, however, is diverse and the BPA collections reveal an interesting connection between him, Britten and Pears.

Burgon was introduced to Britten by way of a letter sent in November 1969 from his friend, producer Basil Coleman. Coleman was writing to compliment Britten on the recent television recording of Peter Grimes and he also took the opportunity to extol young Burgon’s ability as a composer. He told Britten his talent was worth encouraging and added that Burgon was going to send Britten an example of his music. Shortly after a small number of manuscripts with accompanying tape recordings arrived in Aldeburgh. Burgon asked Britten whether they might be considered for performance at the Aldeburgh Festival. Although they could not be included in the upcoming Festival, Britten noted, ‘I think you have a great deal of creative vitality and many exciting ideas, and I should like to see your music again from time to time.’

Burgon responded enthusiastically. He wrote about various projects he was engaged on and added that he soon hoped to embark upon work on an opera. Burgon also sent the score of his latest piece, ‘a fantasy for voices, narrator and instruments’ called St Joan. This had been written in collaboration with the novelist Susan Hill (whose novel Strange Meeting had been inspired by War Requiem and who knew Britten). St Joan was to receive its first performance at the Eleventh Little Missenden Festival of Music and the Arts in October 1970 (Britten’s Songs and Proverbs of William Blake was also included in the programme). The brochure Burgon sent to advertise the Festival included news about the forthcoming television opera Owen Wingrave, which was to feature one of the Missenden performers, John Shirley-Quirk.

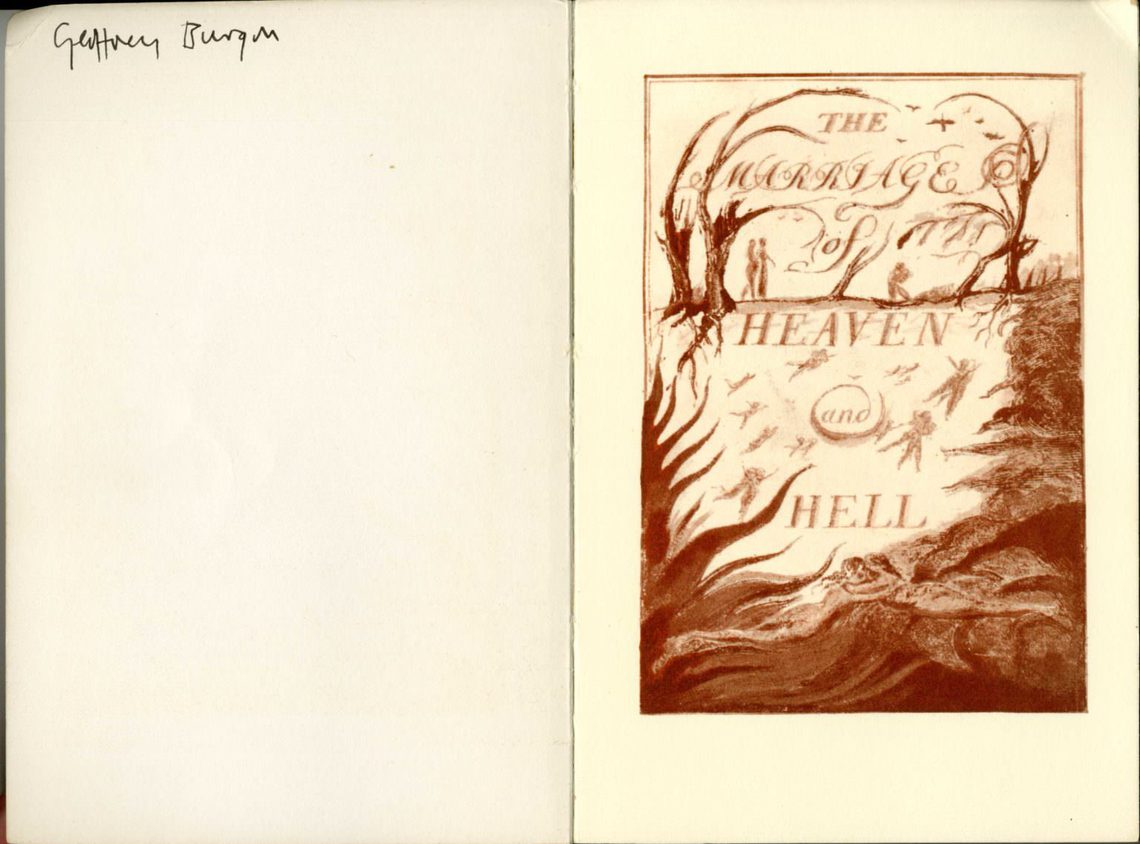

Title page and signature in Geoffrey Burgon’s copy of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, held in the Britten Pears Library

This letter appeared to be the last contact, at least via correspondence, between the two. In the following years Burgon’s career flourished. He produced a number of scores for orchestra, stage, choir and chamber ensemble. Like Britten, he composed a Requiem (1976) that incorporated the liturgical text of the Mass with poetic ‘commentary’ (the words of St John of the Cross). All of this occurred amid a diverse and prolific career in music for television, where links with Britten arose intermittently. For example, he wrote a score for the BBC Shakespeare As You Like It (1978), directed by Basil Coleman. And he shares with David Myserscough-Jones, set designer for the BBC films Peter Grimes and Owen Wingrave, the honour of having worked on productions of Dr Who: in Burgon’s case, Terror of the Zygons (1975) and Seeds of Doom (1976).

As mentioned, Burgon was keen to work in opera. In fact, it was with opera in mind that he corresponded again with The Red House, a year after Britten’s death, this time writing with an idea for a project which he thought might interest Pears.

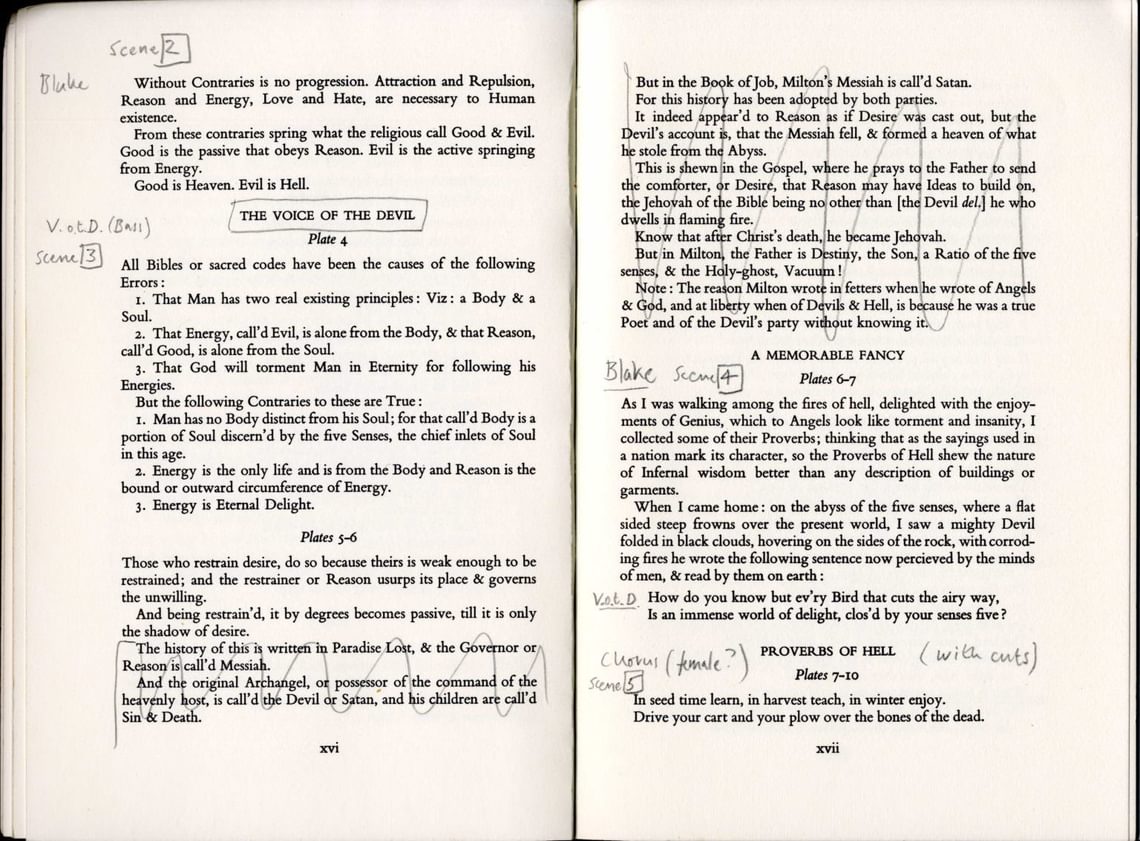

Burgon’s annotations for the schema of his proposed theatre piece

English National Opera was considering commissioning Burgon to write a one act opera for their 1978-79 season. In a letter to Pears, written in the summer of 1977 Burgon indicated that his thoughts had turned toward a ‘music theatre piece based on William Blake’. At this stage, his concept of the piece as a whole was hazy, although he did have a very clear picture of Pears ‘in the leading role.’ Burgon’s correspondence with Pears, like that with Britten, gives an impression of an enthusiastic yet self-effacing person, as Basil Coleman pointed out to Britten in his letter of 1969. Burgon hoped he was not being presumptuous in suggesting the idea to Pears, particularly as he was unsure as to whether the singer knew any of his work. (In a follow-up letter to arrange a meeting between the two he noted that a piece of his was to be broadcast on Radio 3 the following day which would give Pears a taste of his music.)

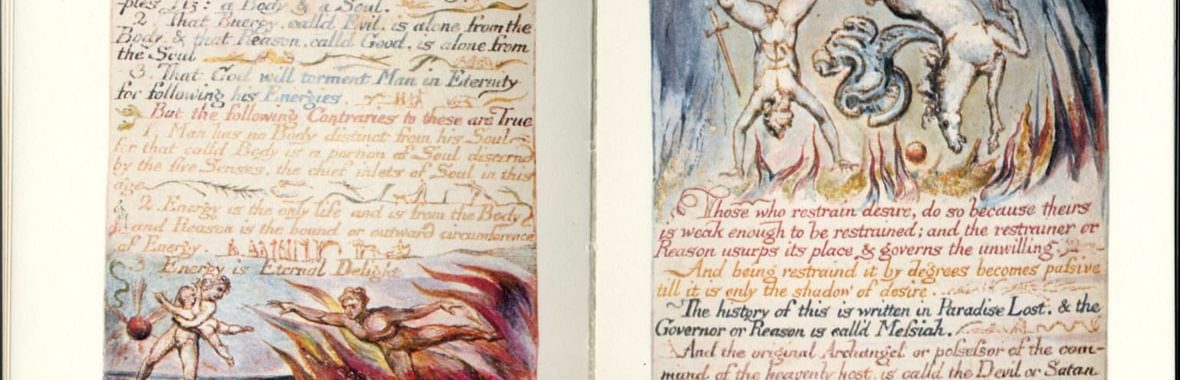

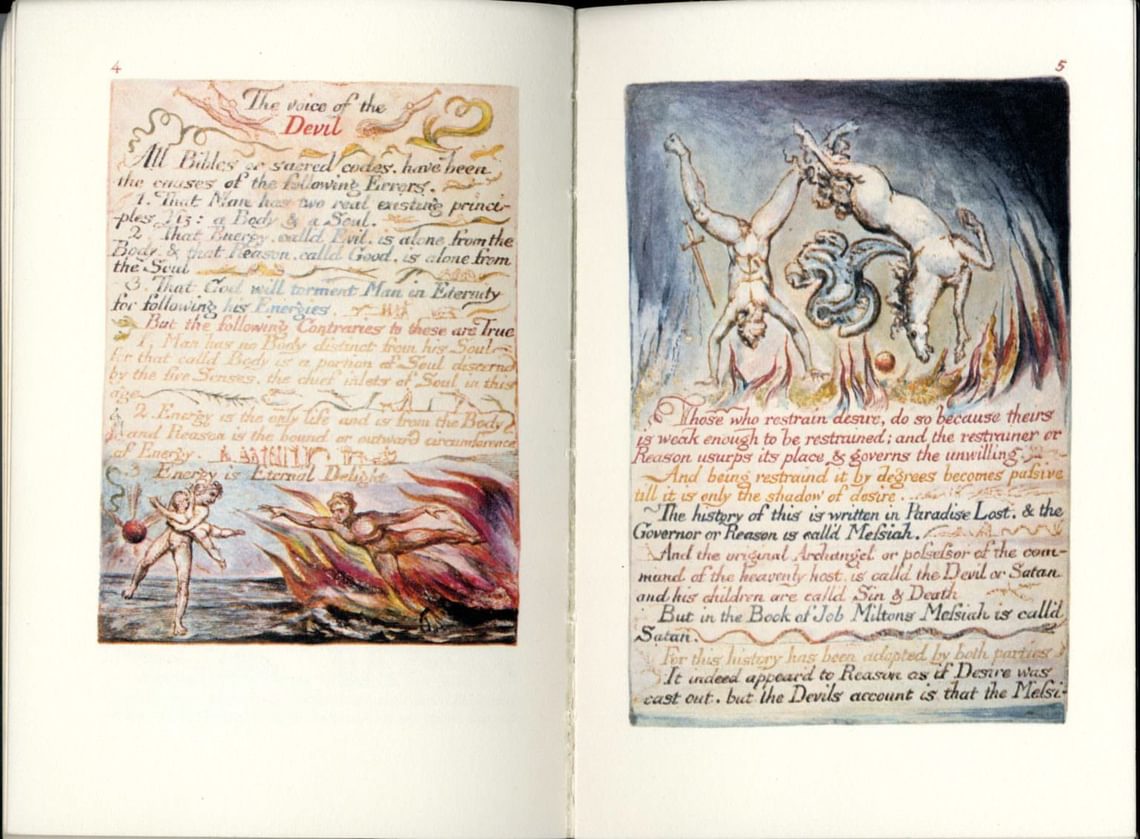

Reproduction of Blake’s illuminated text in Keynes’s 1975 edition of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

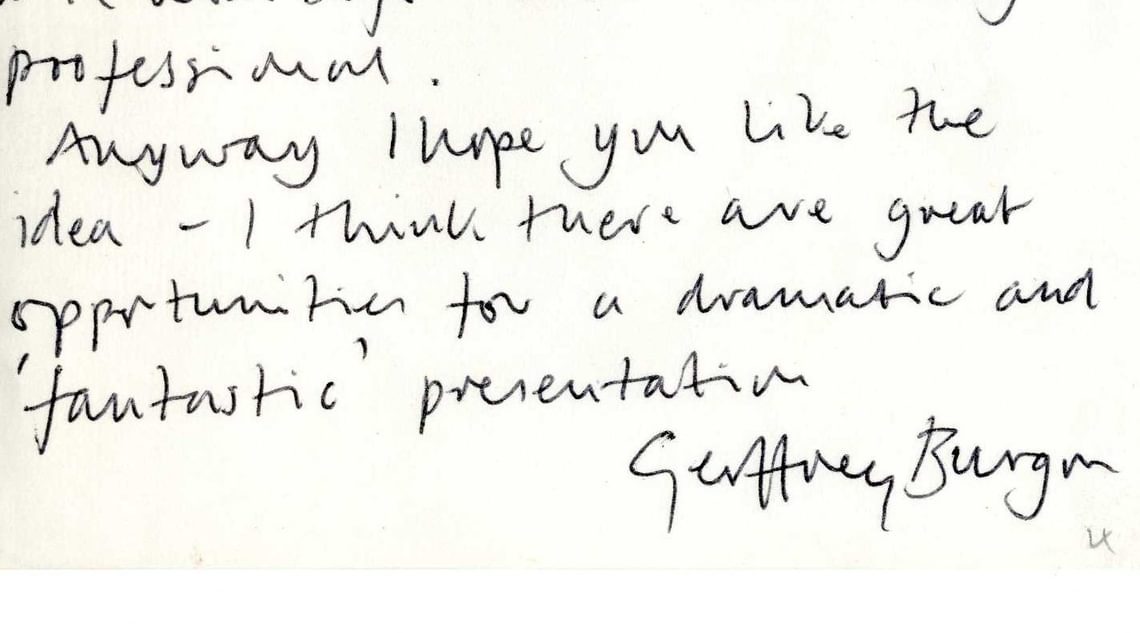

By October 1977 Burgon had formulated the structure for the opera and he suggested, ‘I now have a clear idea of how I want to approach the Blake piece and I would like to come and talk to you about it again.’ From what can be gauged from Burgon’s correspondence, the work would have incorporated Blake’s poetry, with additional libretto that made links between the verse and the poet’s life. He mentions that had approached both Myfanwy Piper and Peter Porter respectively to undertake the libretto. Piper had not been able to accept, but apparently Porter showed interest. Unfortunately, the project did not eventuate which is a loss as Burgon’s final word to Pears was, ‘I hope you like the idea – I think there are great opportunities for a dramatic and ‘fantastic’ presentation.’

Burgon’s final thoughts on the theatre piece he was discussing with Pears, c. late 1977

This letter also mentions that a copy of Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell had been left with Pears ‘with some ideas for a musical treatment of it.’ The book is a 1975 Oxford University Press edition with an introduction and commentary by Geoffrey Keynes. Burgon’s annotations reveal something of the form and content of the piece. It was to have comprised a dialogue between Blake and the Devil (sung by a bass), with other voices intervening occasionally. Burgon envisaged 12 scenes and Blake would have been on stage throughout most of them. Apart from discussion with the Devil he would also have introduced other narrators, such as an angel (countertenor), the prophets Isaiah and Ezekiel, and possibly a female chorus singing the Proverbs of Hell.

Burgon’s copy of Blake was never returned to him and it looks as though the theatre piece was not taken up by anyone else. What we are left with is an intriguing outline of what might have been. The book came to light as a result of recent cataloguing and, like other volumes in the collection, tells us more than the story printed between its covers. The prospect looked fascinating and, had it come to fruition, it would have been a dramatically demanding role for Pears, then in his late sixties. Those letters from Burgon, who passed away in 2010, suggest that Pears took an obvious interest in the project (enough for him to retain Burgon’s copy of Blake). Given Pears’ own lifelong interest in Blake’s art and poetry it would have been an appropriate role for him to contemplate in the latter stage of his career.

- Dr Nicholas Clark, Librarian