Rostropovich, Menuhin, Richter – asked to compile a list of musicians who worked with Britten and Pears, there are some obvious names. Likewise, asked to name Western musicians who explored Indian culture in the 1960s, most people would come up with names from the world of rock music. Less well known is the way that Britten and Pears, and others from their circle, were exploring Indian music and arts long before Ravi Shankar played at Monterey. As our mapping of the two men’s travels illustrates, they undertook two lengthy Eastern tours, to India and the Far East in 1955-56 and again to India in 1965, performing their own music but also listening to the very different sounds around them. (For Pears, too, it was something of a family pilgrimage, his father having been born in India under the Raj.) In Mumbai in late 1955 Britten became one of the pre-publication subscribers to Quest, the magazine of newly-independent India’s intellectuals, that first appeared the following year.

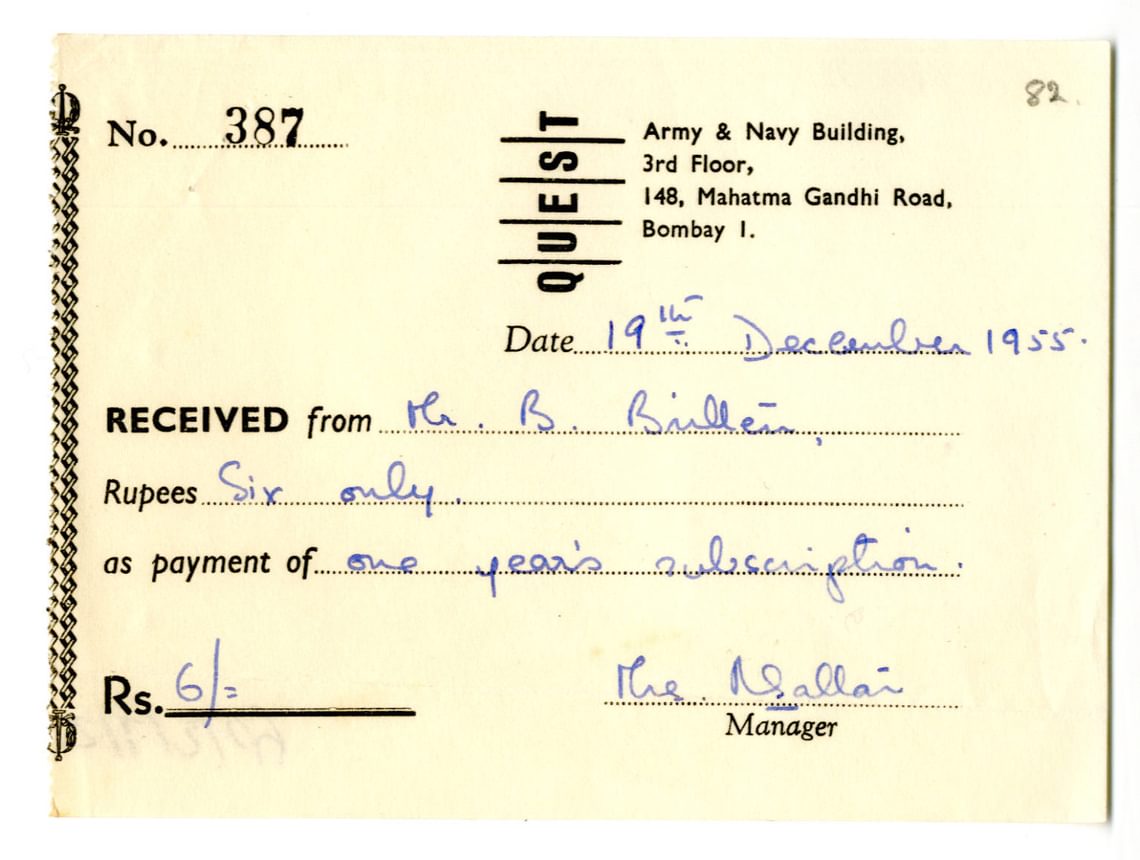

A receipt recording Britten’s subscription to India’s Quest magazine, 1955. (BBF/2/10/82).

The two men’s interest in Indian arts and culture was committed and respectful, and of long duration.

One photograph in the archive sums up Britten and Pears’ interest and this intertwining of European and Indian culture. The date of PH/6/226 is uncertain, but it was taken at some point in the early 1960s. Peter Pears stands apparently on a stage, near the back of a group of ten people of mixed age, sex and nationality, their dress a mixture of Western European and Asian, of suits and saris. This is a gathering of the Asian Music Circle, for over twenty years a force in disseminating knowledge of the arts and culture of the Indian subcontinent to the United Kingdom.

Peter Pears stands on stage with members of the Asian Music Circle, early 1960s (PH/6/226).

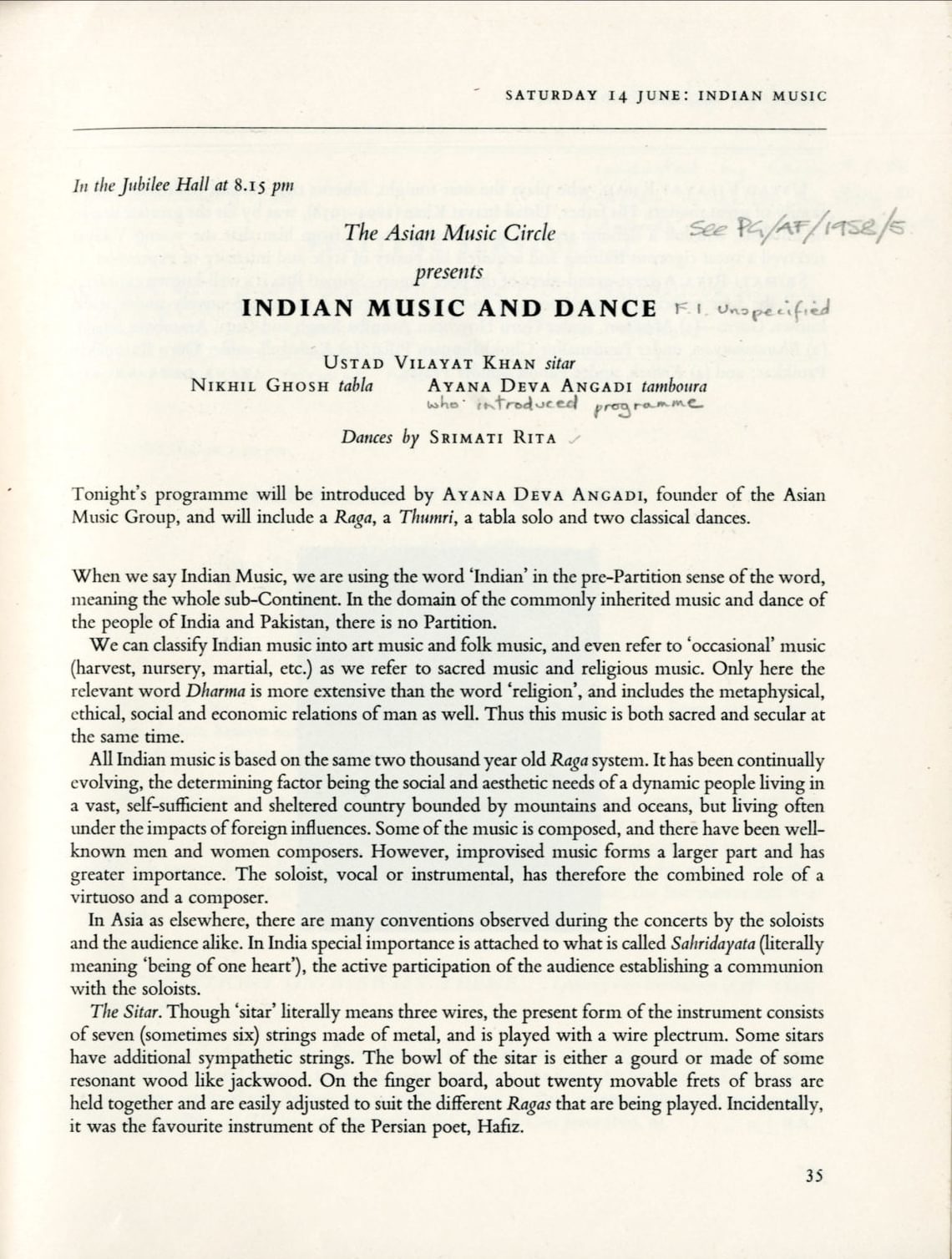

The Asian Music Circle was founded in 1946 by a couple whose marriage spanned the two cultures: Ayana Deva Angadi, writer and political activist, had come to London to study and here married Patricia Fell-Clarke, an industrialist’s daughter who became a painter and, later, a novelist. The two stand either side of Pears in this photograph – Ayana Angadi on the extreme left of the picture and Patricia Angadi just to the right of Pears. The Angadis’ home was the centre of the AMC’s operations and they were its driving force, though Western musicians were prominent as its public faces: from 1953 Yehudi Menuhin was its President, and Benjamin Britten served as a Vice-President for some years. As well as publicising and explaining Indian arts and culture, the AMC played a practical role in securing bookings for Indian musicians: it was through the AMC that the sitar virtuoso Ustad Vilayat Khan performed at the 1958 Aldeburgh Festival, with Ayana Angadi present to give an introductory talk. (Sadly, the Festival programme for that year only explains that Ustad Vilayat Khan and his supporting musicians will perform ‘a Raga’ – akin to saying ‘Mr Britten and Mr Pears will perform a music’ – so we do not know whether the repertoire obeyed the strict rules whereby certain ragas are reserved for particular times of day or seasons; we can only hope that Ayana Angadi was more forthcoming on the day.) When popular culture discovered Indian music in the 1960s the Angadis were on the scene, facilitating this cultural exchange: when George Harrison broke a string on his sitar recording ‘Norwegian Wood’ it was the Angadis who could secure a replacement string in London, Harrison becoming after this a regular visitor to their home.

Page from the 1958 Aldeburgh Festival programme, describing the concert by Ustad Vilayat Khan that year. (PG/AF/1958).

Also on the stage in this photograph are the High Commissioner of Pakistan, His Excellency Mohammad Yousuf, and members of his family. They surround two more figures who had roles to play in cultural cross-fertilisation. The whole party are looking at a small girl in western dress who has clearly just said something that amuses Pears: this is the youngest of the Angadis’ four children, Chandrika (also known as Clare), who went on to be the first Asian model to appear in Vogue. Behind her, in a headdress that towers over the rest of the group, is a dancer whose life-story embodies Western-Indian cultural fusion. Indrani Rahman was born in Chennai in 1930, from her birth the product of cultural fusion: her father, Ramalal Balram Bajpai, was a north Indian who had gone to the United States to study, while her mother, born in Michigan as Esther Luella Sherman, converted to Hinduism on marrying, took the name Ragini Devi, and devoted herself to the revival of Indian classical dance. Her troupe toured in Europe and America, as well as in India; Indrani learned to dance in this company and it was in New York (where, after independence, her father became India’s consul-general) that she met the architect Habib Rahman, who had been asked to take a small non-dancing part in a performance. Aged fifteen she eloped with Rahman and married him, eventually having two children. This crossed yet another cultural divide, as Rahman was Muslim. During this period her career straddled the worlds of Indian tradition and western consumer culture: she was devoted to learning the classical dance tradition of Orissa, but also undertook some advertising work to finance her studies (an article in The Hindu records that she deliberately excluded this work from her scrapbooks) and in 1952 entered and won the first Miss India contest. From her mid-twenties, however, she was able to concentrate firmly on dance, turning down offers of film roles and working, as her mother had done, as an ambassador for traditional Indian dance. It is in this life-long role that we see her on stage with Peter Pears, smiling down at the young Chandrika Angadi.

One photograph, on a stage probably in London, at an unknown date, but on that one photograph we see many links between Western Europe and the Indian subcontinent: we see people devoted to explaining one culture to the other, to exploring both, or whose heritage embodies this cultural cross-fertilisation. Long before the hippy trail led east to the subcontinent, Britten and Pears had made the journey: the people in tie-dye get all the publicity, but the ones in shirt and tie were ahead of them.

- Dr Christopher Hilton, Head of Archive and Library