One of the fascinations of an archive is the way that, no matter how apparently focused its content may be, other topics creep in at the edges. The world’s largest free-standing composer’s archive, the collection at the Red House, gives detailed chapter and verse on the professional activities of Benjamin Britten, Peter Pears and their professional collaborators. We can also use it to reconstruct their responses to the times in which they lived, their lifestyles, and the town in which they lived. And sometimes a few items or a single piece of paper illuminate a whole forgotten area, the sort of transaction that would have been mundane at the time but now seems part of a vanished world.

The papers of Peter Pears are not yet fully catalogued and much, we can assume, remains to be discovered in them. One area that has been explored in detail is the run of files containing financial receipts: as in Benjamin Britten’s papers, these were retained to be used as evidence if Pears were to be audited by the tax authorities (and subsequently escaped the destruction that often overtakes such “ephemeral” material). In one of these, the cataloguers discovered a ticket that takes us back to a long-vanished means of travel to the European mainland: the Channel air ferries, which operated between England and France for a relatively brief time during the 1950s and 1960s.

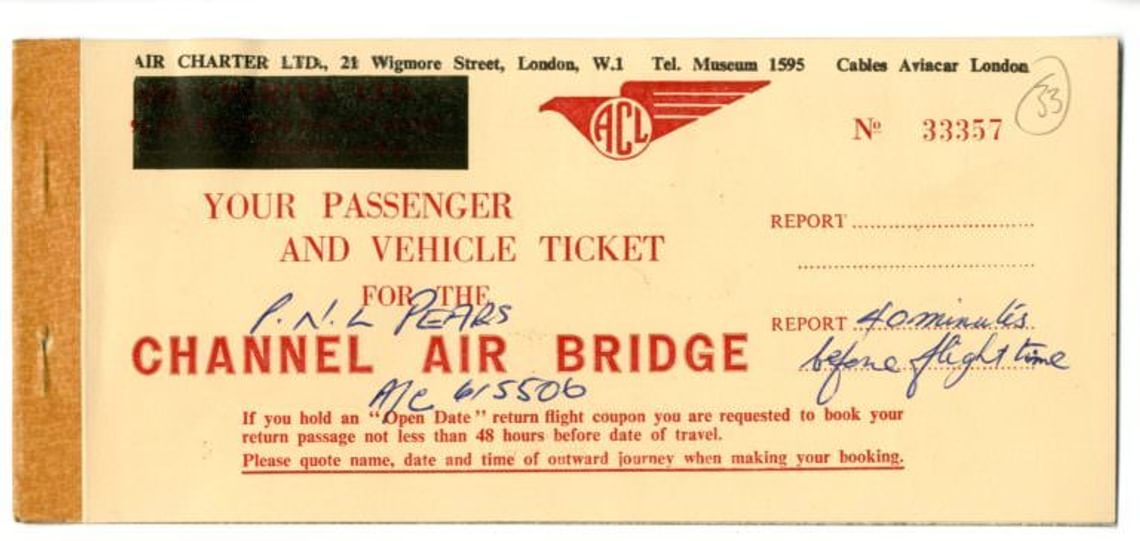

Peter Pears’ Channel Air Bridge ticket from 1959.

The concept was a simple one: a freight aircraft would carry a few cars, plus their occupants, a short hop across the English Channel. At first two companies operated, both beginning in 1955: Silver City Airways flew from the airfield at Lydd, on Romney Marsh, to Le Touquet, a little over forty miles away, whilst Channel Air Bridge (set up by Freddie Laker, who later pioneered the cheap, no-frills model of air travel with his Skytrain service to New York) flew from Southend to Calais. In each case the flight took about half an hour. Each company diversified to set up a network of various routes covering various ports and the Channel Islands; the two companies merged in 1962.

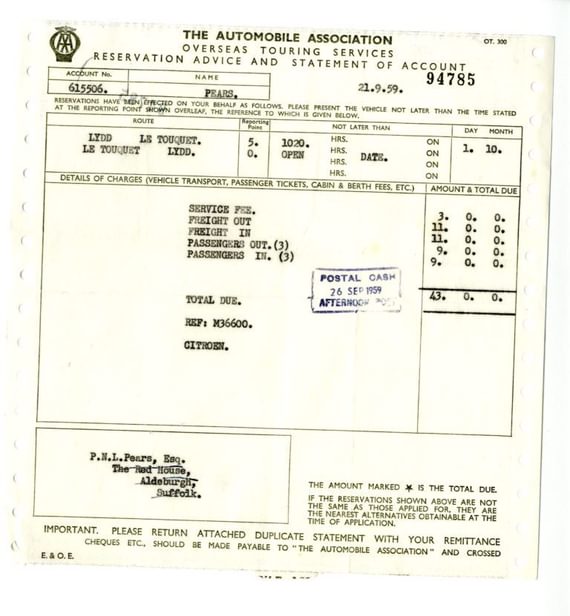

Ticket for Britten, Pears and Mary Potter.

The service was always a premium one; not merely because of the speed, but also because of limited capacity, each aircraft accommodating only three cars. The alternative for someone wanting to take their own vehicle to France rather than hire another vehicle there, however, was to have the vehicle lifted laboriously into the hold of a ship, so the air ferry had a market. In late 1959 we see Pears, Britten and their friend the artist Mary Potter – from whom they had bought the Red House not long before – travelling with a Citroën car on the air ferry between England and France. The documents are slightly confusing: there are printouts recording a booking to travel between Lydd and Le Touquet in early October, and the return half of a ticket on the Southend-Calais route at the end of the month.

Reservation advice and statement of account for their journey to France.

Presumably the party’s travel plans changed and they switched to later travel on a route whose English end was more convenient for their Aldeburgh home. Connoisseurs of retro travel, then, get two things for the price of one, with both routes represented.

Car and passenger cancellation information.

Pears and Britten travelled by this method at perhaps its peak: it flourished at a precise historical moment. In the post-war period, car ownership was on the rise, but not yet at a point at which more mass provision was necessary. The Bristol Freighter aircraft that formed the backbone of all routes, a wide-bodied aircraft with clamshell doors in the nose into which vehicles were loaded, had been developed during the Second World War for military transport (though the war ended before the prototype flew). A market coincided with the available technology, briefly. However, from the beginning the writing was on the wall for the air ferry. The same war that had driven the development of the Bristol Freighter aircraft had also seen the development of the LST (Landing Ship, Tank): a shallow-drafted craft equipped with bow doors and a ramp to enable shore-to-shore transport of tanks and other military vehicles without the need for a full-scale harbour or quayside. Military surplus craft owned by the Atlantic Steam Navigation Company began the bulk transport of cars between Tilbury and Rotterdam in 1946. By 1953 roll-on-roll-off (RoRo) craft of this type were plying between Dover and Calais. In the ensuing years, RoRo vessels grew larger, faster and more frequent in their operation; in contrast, the air ferry remained very much in its original form, with aircraft designers showing no interest in developing larger-capacity planes. Although for speed it was not to be rivalled until hovercraft arrived on the Channel routes in the second half of the 1960s, it was sidelined by the way RoRo ferries now offered similar convenience for a mass market. In hindsight, the air ferries’ peak was at the turn of the 1950s and 1960s: precisely the point at which we see Britten and Pears travelling that way.

Bristol Type 170 Freighter aircraft of Silver City Airways.

Before their demise, however, the air ferries had one last moment of pop culture glory. In their 1966 film That Riviera Touch Eric Morecambe and Ernie Wise, travelling to the south of France, take their car on the Lydd – Le Touquet route. It’s a matter of constant regret that Britten and Pears never made a guest appearance on the Morecambe & Wise show, but the two couples do seem to orbit around each other and here is something that they have in common – in addition to both having worked repeatedly with Andre Previn.

- Dr Christopher Hilton, Head of Archive and Library