Close inspection of the bookshelves in The Red House reveals a number of volumes that must have had special resonance for Britten and Pears. These titles come under the category of ‘gay literature,’ though they were part of The Red House library well before that term gained common usage. What is interesting is that, whether fiction or fact, some of the narratives in these books bear occasional resemblance to Britten and Pears’ own story.

Title page for Mary Renault’s The Charioteer (London: New English Library, 1959)

Mary Renault’s classic The Charioteer was first published in 1953. Britten and Pears owned a now well-foxed reprint of 1959. Avid readers of Renault, her tales of Alexander and Theseus also sit on their shelves. The Charioteer, however, may well have struck a more personal chord as part of its narrative bore a broad connection with Britten and Pears’ own situation. The book tells the story of Laurie, a soldier recuperating from war injuries sustained in Dunkirk. It follows the choice he makes between his love for a naval officer and his feelings for a conscientious objector working as an orderly in the hospital where he is being treated. Homosexuality and the refusal to take up arms during wartime were controversial subjects when the book was written and remained so for many years. As Pears specifically pointed out, a decade after the novel’s publication, these were issues with which he and Britten still had to contend. ‘We are after all queer & left & conshies,’ he wrote in a letter of July 1963, ‘which is enough to put us, or make us put ourselves, outside the pale.’

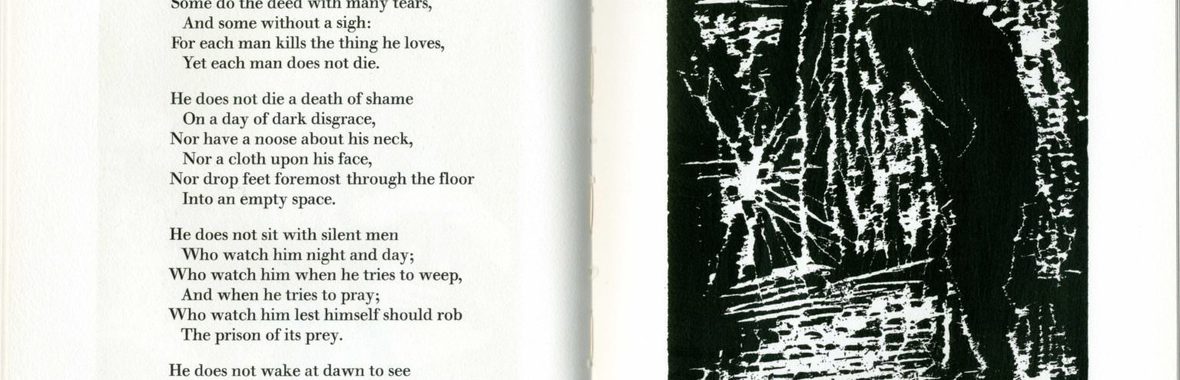

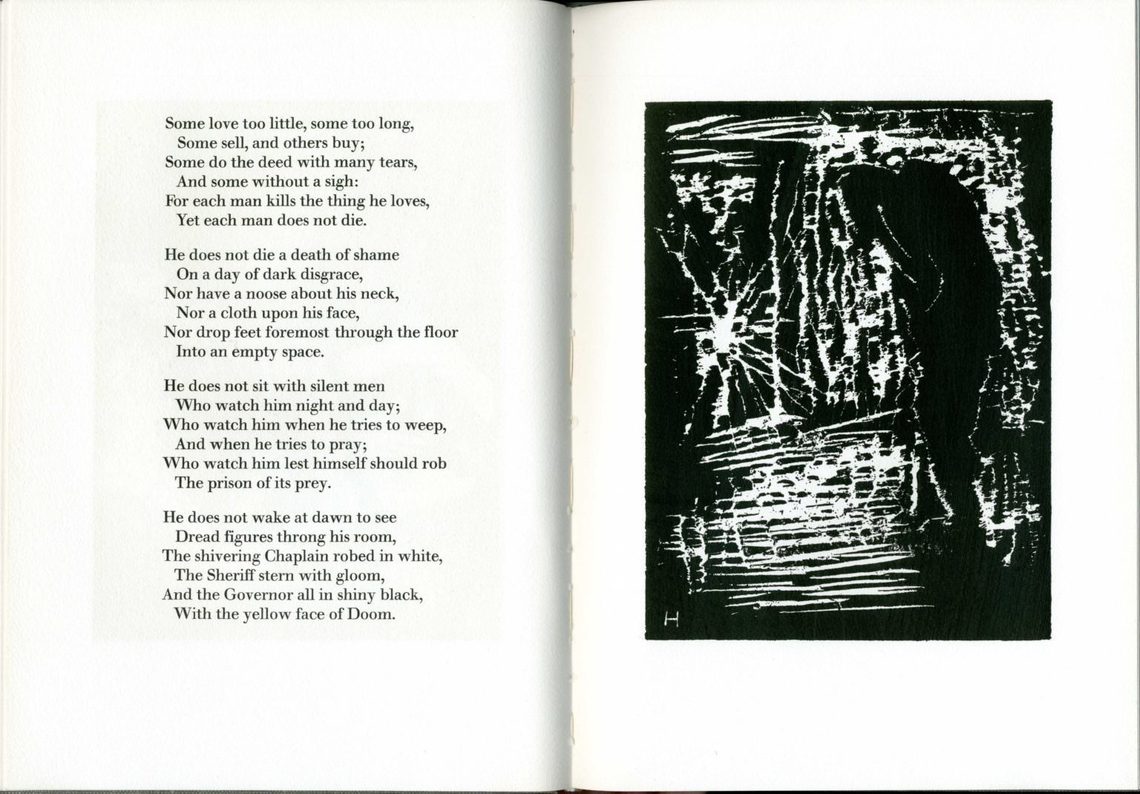

This awareness of being ‘outside the pale’ relates to one of The Charioteer’s most significant themes, one that became a staple of much gay fiction: the stigma of being made to feel ‘different,’ particularly when faced with society’s prejudices. The pain of this isolation is expressed in Wilde’s The Ballad of Reading Gaol, a copy of which (with haunting illustrations by Erich Heckel) can also be found in Britten and Pears’ collection. Renault explored the stigma in two ways in her novel. “Take shame to yourself … Conscientious, I never heard such stuff,” one of her characters, the imperious Mrs Chivers, rails at Andrew, the CO. Obviously, it’s an attempt to induce shame for the moral stance he has taken. One can only guess how much greater Mrs Chivers’ vitriol would have been if she had been aware of Andrew’s homosexuality. It’s a damning and unfortunately all too realistic depiction of the way ‘different’ people were seen and treated.

Oscar Wilde’s The Ballad of Reading Gaol, illustrated by Erich Heckel (New York: Ernst Rathenau, 1963)

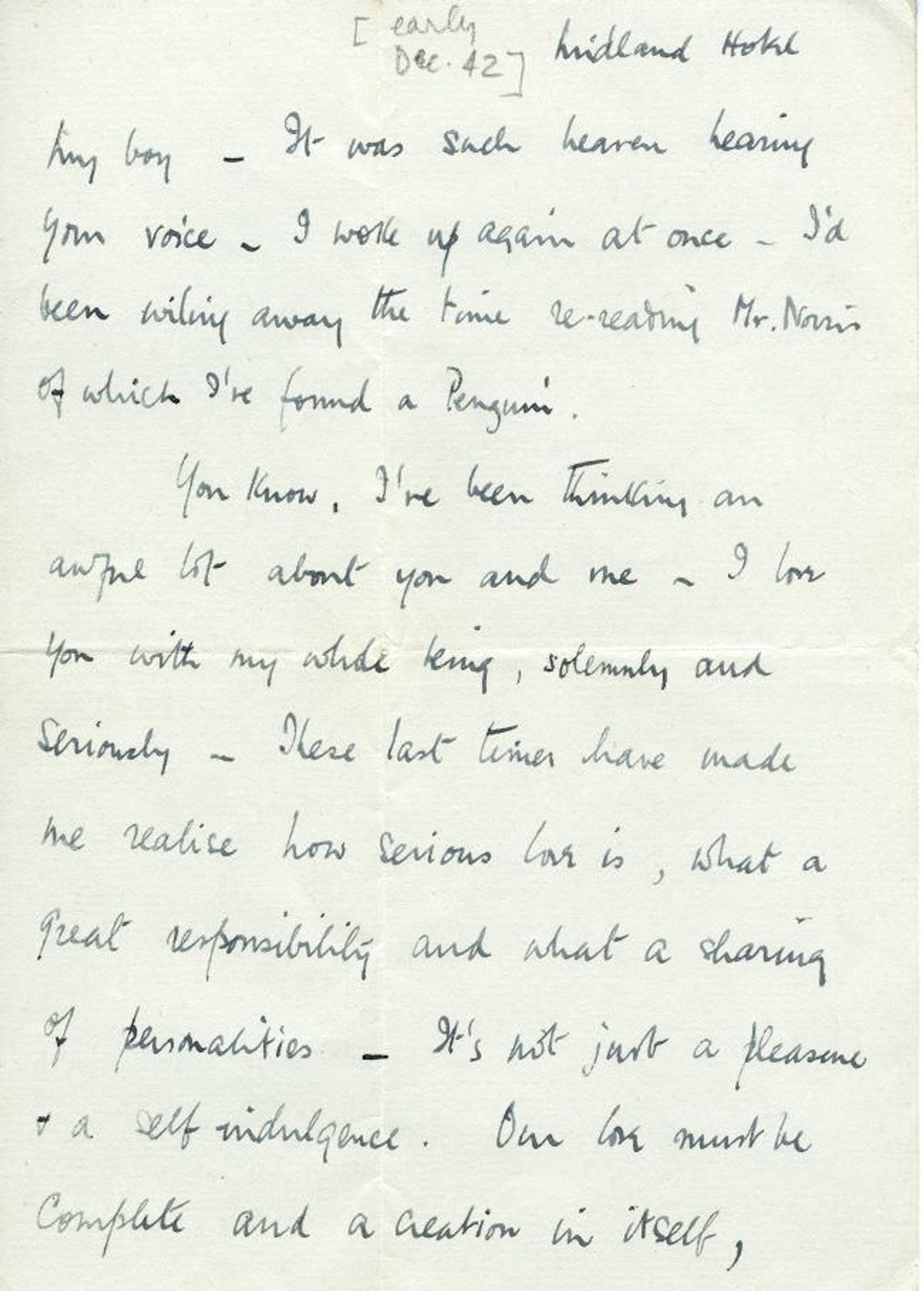

The discomfort Andrew feels about his sexuality is touched on later in the novel when he describes the constraint he feels in not being able to act as freely or as naturally with others as he can with Laurie. ‘It’s all right when I’m with you,’ he confesses. ‘I don’t have the feeling of being different, then.’ In real life ‘difference’ such as this formed the basis of Britten and Pears’ relationship. Admittedly, their love had to be officially concealed from the public but privately they were able to make an open declaration of their feelings. ‘I love you with my whole being,’ Pears stated in December 1942 (approximately the era in which The Charioteer is set), ‘solemnly and seriously –These last times have made me realise how serious love is, what a great responsibility and what a sharing of responsibilities’.

Freedom to love is explored in E.M. Forster’s Maurice, a draft of which Britten read before the book’s eventual publication, which happened after the author’s death. ‘It reads much better now,’ Britten wrote to the Princess of Hesse soon after Maurice finally saw the light of day in 1971. The novel provided insight into the disgrace homosexual men endured and, in this case, overcame in early 20th century England. The story has been criticised for presenting perhaps too happy an ending but it appeared at a time when disgrace and stigma were gradually being eroded, when ‘gay’ had become a synonym for ‘homosexual.’ Britten and Pears were cautious of using that term. They couldn’t separate it from its traditional meaning. In the mid-1970s Pears suggested that ‘gay’ gave a ‘false impression’ of a life often beset with worry and the self-conscious need to hide one’s true self. That had been the case for men of his generation, although he and Britten had been fortunate in the acceptance gained from friends and family. Pears was, however, in no doubt that there still existed plenty of disapproval from the Mrs Chivers of this world.

Original cover for Christopher and His Kind (New York: Avon Books, 1977)

His awareness of public scrutiny into and public censure of his and Britten’s private world persisted, even when it had become widely known that they were life partners. Public opinion mattered little to them late in their lives although we get a hint of nervousness in Pears’ letter to Britten of November 1976. ‘Christopher has written a book about the Thirties, but has “left out all the names.”’ This was in reference to the book Christopher and his Kind, Christopher Isherwood’s recollections of the era in which Britten entered the more daring homosexual ambit of fellow artists like Isherwood and W.H. Auden. Here Isherwood speaks candidly about how his sexuality has partly defined who he is, how it made him into the writer he became. He suggests that it was a source of his creativity.

Pears acknowledged something similar 34 years earlier, amid a casual remark about a book. Christopher and his Kind sits on his and Britten’s Library shelf, beside a collection of other titles by Isherwood, one of which is Mr Norris Changes Trains. ‘I’d been wiling away the time re-reading Mr Norris of which I’ve found a Penguin,’ Pears states in that letter of December 1942. Like Isherwood, Pears noted at the end of his letter that self-realisation and self-acceptance inspired his own creativity and creative relationship with Britten. ‘Our love must be complete and a creation in itself,’ he declared, ‘a gift which we must be fully conscious of & responsible for.’

Image gallery

Open an image gallery

Open an image gallery