In 1975 Benjamin Britten was a sick man: two years before he had suffered a stroke in the course of an operation to replace a failing heart valve, and his health had never fully recovered. His mobility was restricted, and he was physically fragile. He, and those around him, seem to have felt that he had only limited time left.

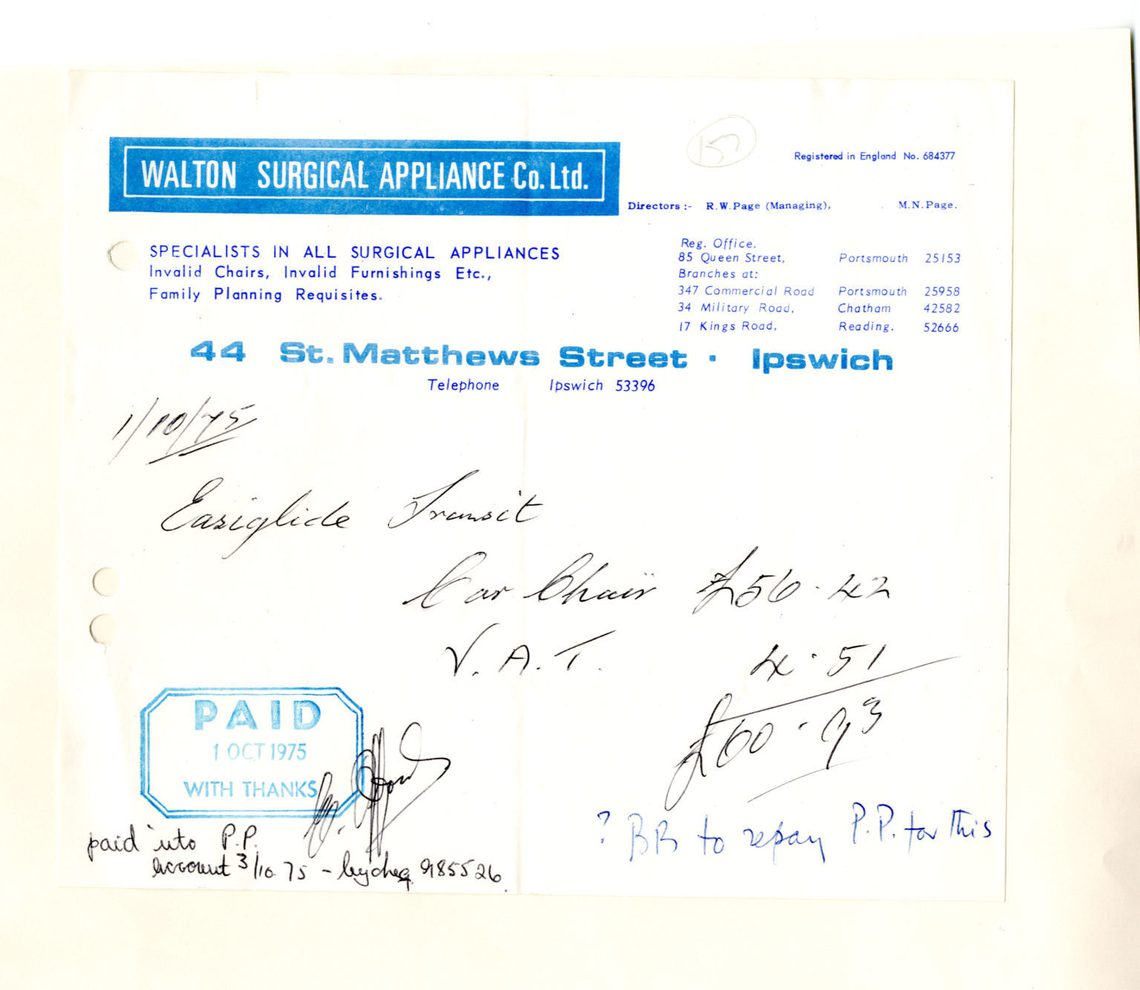

Receipt for the purchase, including a note that Britten is to repay Pears who paid for it on his account.

One little item in Britten’s financial receipts brings this home to the researcher. On the first of October 1975, the papers record a purchase from the Walton Surgical Appliance Company Limited of St Matthews Street, Ipswich: an Easiglide car seat (archive reference: BBF/2/30/157). The purpose of this device was to make it easier to transfer a patient from one sitting position to another, bridging a gap or dealing with a change in height. In this case, it is an indication that Britten was spending much of his time in a wheelchair, and needed help transferring between this and the seat of a car.

There are other little details that emerge from this document: every archive document crystallises a moment and is the product of a very precise context, a context we can infer from details on the paper. The letterhead of the receipt encapsulates a piece of social history: the firm supplies medical equipment, but amongst the various items of hospital kit available there is also ‘family planning requisites’: an indication of how contraception was at that time something to be found only at the chemist’s or in other medical contexts, a contrast to the way that condoms are now available on supermarket shelves. Another piece of social history is scribbled on the document: a note that this was bought with money from Pears’ account and a suggestion that Britten should transfer some money to pay for it. As gay men at a time when their relationship was illegal, Britten and Pears had had to manage their finances in a way that did not give away the nature of their partnership. To have a joint bank account, or property in common, would make it clear that they were a couple: instead, we see them carefully maintaining separate bank accounts, working out whether one has spent money on the other’s expenses, and transferring funds between the two accounts to ensure that each had paid what they owed. At this time, of course, their relationship was legal, but the habits of a lifetime are not easily cast off (and to change the financial structure of their personal and professional partnership would have meant upheaval, and been a change from which perhaps only their accountants and lawyers would profit), so we see them here continuing to manage their money the way that they always had.

Photograph taken by Rita Thomson with, left to right, Britten, Pat Servaes, Esteban Cerda and William Servaes seated by the lagoon in Venice, November 1975.

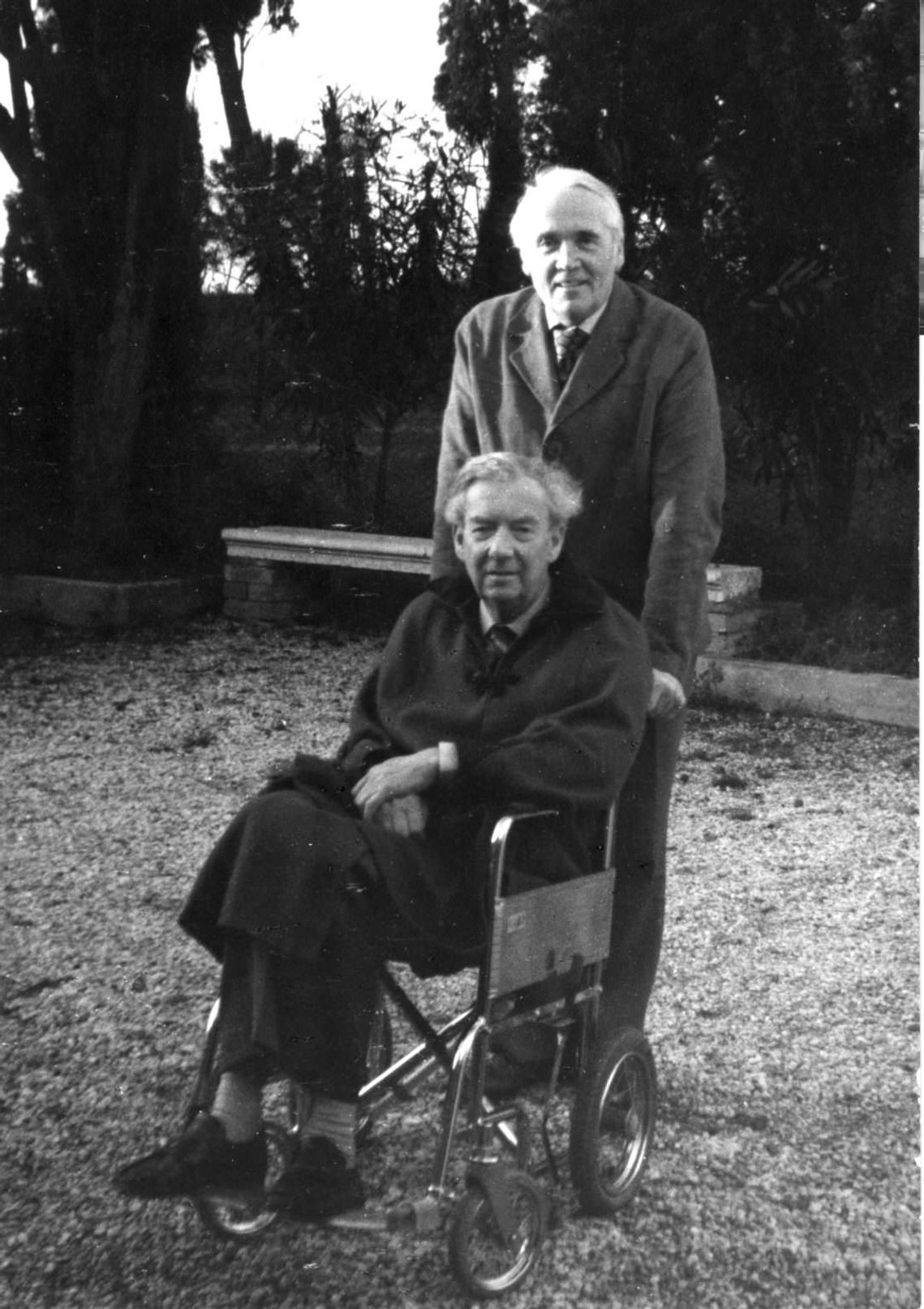

It would be easy to construct a rather depressing narrative from this document, one dominated by Britten’s increasing frailty, but this is not the whole story. And Britten was by no means confined to the house. In the autumn of 1975 Britten visited Venice, the driving force being William Servaes, Director of the Aldeburgh Festival. A former naval officer and businessman, Servaes was used to dealing with obstacles rather than giving in to them, and refused to allow Britten’s health to prevent him taking this holiday in a place he had long loved. Photographs from 1975 show Britten, William Servaes and his wife Pat, and Britten’s ever-present nurse Rita Thomson, in the centre of Venice and exploring out as far as Torcello. In most, Britten is in a wheelchair (pushed by Servaes): the Easiglide seat we saw him buying in October may well have been the thing that got him there.

- Dr Christopher Hilton, Head of Archive and Library

Photograph of Britten leaning on the balustrade at Hotel Danieli looking at the passers-by in the street below. The outline of Rita Thomson, standing next to him, is just visible. November 1975. Photographer: William Servaes.

William Servaes pushing Britten in a wheelchair by a bridge over a canal. On the steps stand Pat Servaes, with her back to the camera, and Esteban Cerda. November 1975. Photographer: Rita Thomson.

William Servaes and Britten on Torcello island, Venice, 18 November 1975. Photographer: Rita Thomson.