It might be difficult to think of a connection between Britten and that great tradition of British cinema, the Hammer Horror film series, however a rather important link can be found in the collections of The Red House.

James Bernard (1925 – 2001) was a pupil and aspiring composer at Wellington College, Berkshire where artist Kenneth Green had taken a teaching post. Britten met Bernard during a visit to the school in 1943, when he came to consult Green on the set designs for the first production of Peter Grimes. One of the results of that early meeting was a piece of ‘editing’ that Britten performed on a work Bernard had written for piano, trombone and percussion (for which Britten invented a new percussion instrument).

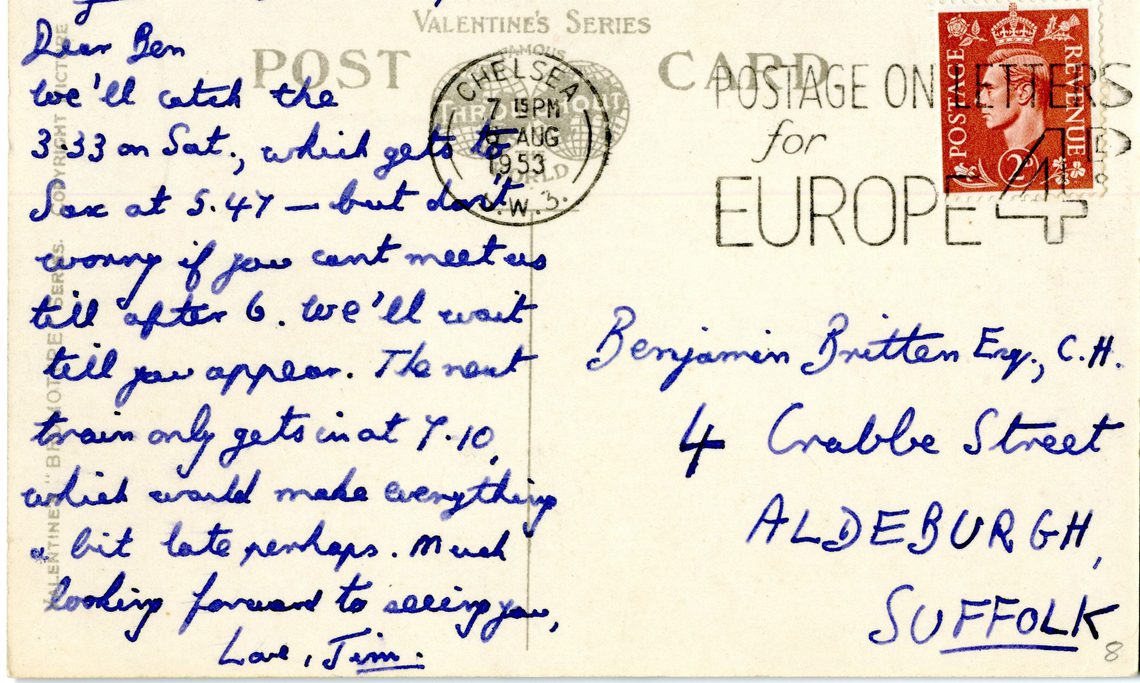

A postcard from James Bernard to Britten, August 1953

A friendship evolved and several letters in the collection tell us about the interest Britten took in Bernard’s future career, an interest that included advice offered on education. ‘Either the R.C.M. [Royal College of Music] or the R.A.M [Royal Academy of Music] would be the best thing,’ suggested Britten. ‘You could take piano & composition & get a good general musical education as well.’ Like Britten, Bernard attended the R.C.M. where he studied composition with Herbert Howells. Although Britten and Bernard shared a mutual indifference for the College, Britten believed the tuition offered by a working composer would be beneficial; advice similar to that given to him by his own mentor Frank Bridge. There must be ‘more time for composition’ he insisted to Bernard. ‘I don’t know how this can be worked, but Howells might help. I hope he’s sympathetic & will help you get things performed.’

In 1951 Britten invited Bernard to work on preparing the full score of his opera Billy Budd for publication. Britten, however, worried that he might have felt the work to be mundane. In October of that year, he invited Bernard to attend forthcoming rehearsals at Covent Garden, adding in his letter that ‘I hope that the results of [working on Budd] aren’t all negative, & that you’ve learned a little about how to (& how not to) write an opera.’

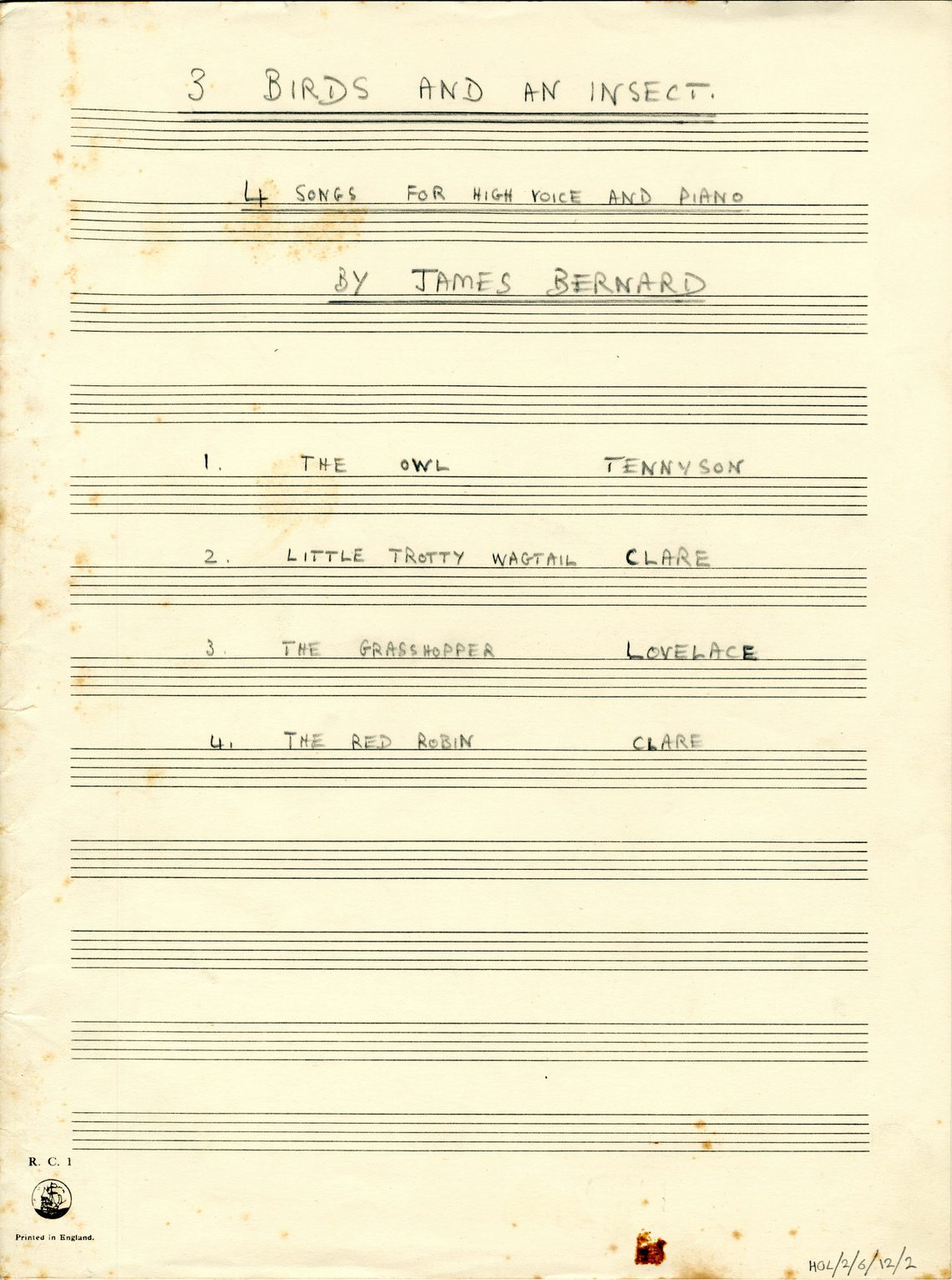

Title page of an early manuscript by James Bernard sent to Imogen Holst.

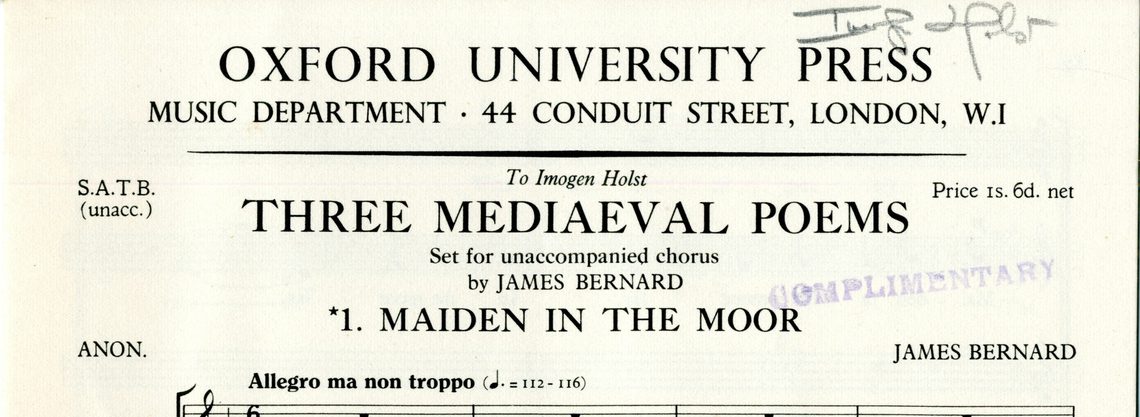

Britten also nominated Imogen Holst as another source of advice on composition. She was highly valued as a mentor and a few early manuscripts of Bernard’s still exist in the Holst Archive. Her influence can be gauged by the fact that his first published work, a setting of Three Medieval Poems, is dedicated to Holst.

Imogen Holst’s copy of the published version of Three Medieval Poems

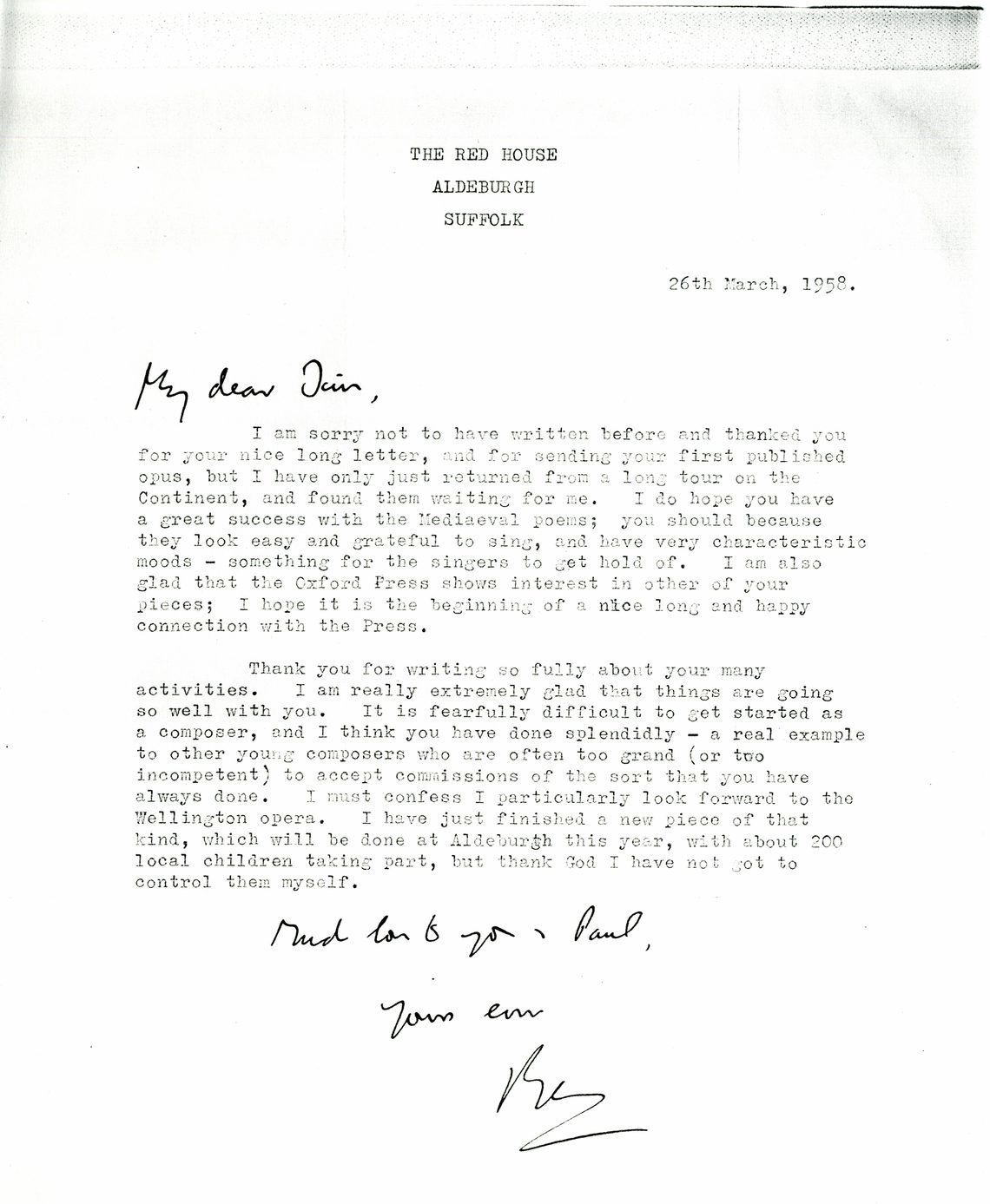

A letter to Britten of March 1958 discloses several significant milestones in Bernard’s professional life, which was clearly progressing at a pace. He describes writing a clarinet sonatina, with hopes for performance by Gervase de Peyer. As Britten indicated (see his letter of 26 March 1958 below), embarking on a career as a young composer was a challenge. By the late 1950s a major source of income for Bernard had taken the form of ‘much orchestral writing for film’, what he called ‘the equivalent of five bad symphonies at least!’ Added earnings came from the composition of a ‘pop number’ recently recorded by Vera Lynn and originally based on a piece composed for Julian Bream that was featured in the Rod Steiger film Across the Bridge.

Bernard no doubt had Britten’s comments about Billy Budd in mind when he mentioned that he was going to have to turn down film music in order to concentrate on Music from Mars, a ‘space opera’ commissioned from Wellington College, with libretto by Bernard’s life partner, screenplay writer Paul Dehn. Britten was sceptical about the opera’s future, but Bernard later informed him that staff and pupils had much fun performing it and that interest in future productions was being received from further afield.

Britten’s letter of congratulation on publication of James Bernard’s Three Medieval Poems, 1958.

Also of interest in Bernard’s 1958 letter is his stating that he had completed ‘nearly 40 minutes worth of bangs, crashes and hideousness for a new film of “Dracula”’. This was one of numerous projects he would undertake for the Hammer Film Production series. The mid-to-late 1950s was the beginning of a golden age for Hammer’s adaption to the screen of some of the great horror stories. The company is now synonymous with this gothic entertainment and Bernard went on to provide scores for some of its best-known classics; films such as The Quatermass Xperiment (1955), The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) as well as the afore-mentioned production of Dracula which propelled Christopher Lee into stardom. Lee and fellow Hammer stalwart Peter Cushing bear a connection with a reference Bernard made in another letter to Britten, when he said he was breaking off from work on Music from Mars for three weeks ‘to write music for a new film of “The Hound of the Baskervilles”’ – now regarded as one of Hammer’s most acclaimed productions.

Although he composed for other types of film, it is the Hammer soundtracks for which Bernard is now best remembered. He was too self-deprecating when describing his film music as ‘bad symphonies’. The Hammer scores in particular have always been recognised as an essential component to creating mood-setting, building suspense and heightening the viewer’s terror. Hammer has achieved considerable status in the history of cinema and Bernard’s scores are part an honourable legacy.

Incidentally, Bernard achieved recognition for his work in film with the award of an Oscar, although not for music. He and Dehn shared the 1952 Academy Award for Best Story for the film Seven Days to Noon. The Archive holds Dehn’s draft of a sea shanty for Billy Budd, which was never used in the finished opera. He wrote the libretto for Lennox Berkeley’s one-act opera A Dinner Engagement (1954) and Castaway (1967) and eventually produced screenplays for films such as Goldfinger (1964), The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1965), Murder on the Orient Express (1974) and several instalments in the Planet of the Apes series.

Even though Bernard saw little of Britten in the ensuing years he maintained a lasting recollection of the importance of his connections with Aldeburgh. As he stated in his letter to Britten of 1958 ‘my gratitude to you, Peter and Imogen for all your guidance, encouragement and help is unceasing and unbounded.’

For further information on James Bernard’s friendship with Britten see John Bridcut, Britten’s Children, London: Faber, 2006

- Dr Nicholas Clark, Librarian

Read more Archive Treasures...

Archive Treasures: The story of a Holocaust survivor and a musical legacy

We mark the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II, and of the liberation of the death camps with the story of a special…

Archive Treasures: Armenian Amphora

Among the many treasures on display at the Red House is the splendid Armenian amphora. It dates from the Urartu era, a civilization which, from the…

Archive Treasures: The English Opera Group

The English Opera Group collection forms part of the Britten Pears Arts Archive which documents the lives and work of Britten and Pears, as well as…