We know several stories about Britten being lured back to write for the big screen. Few such tales straddled the decades like that of his hope to work with John Gielgud on a film version of The Tempest.

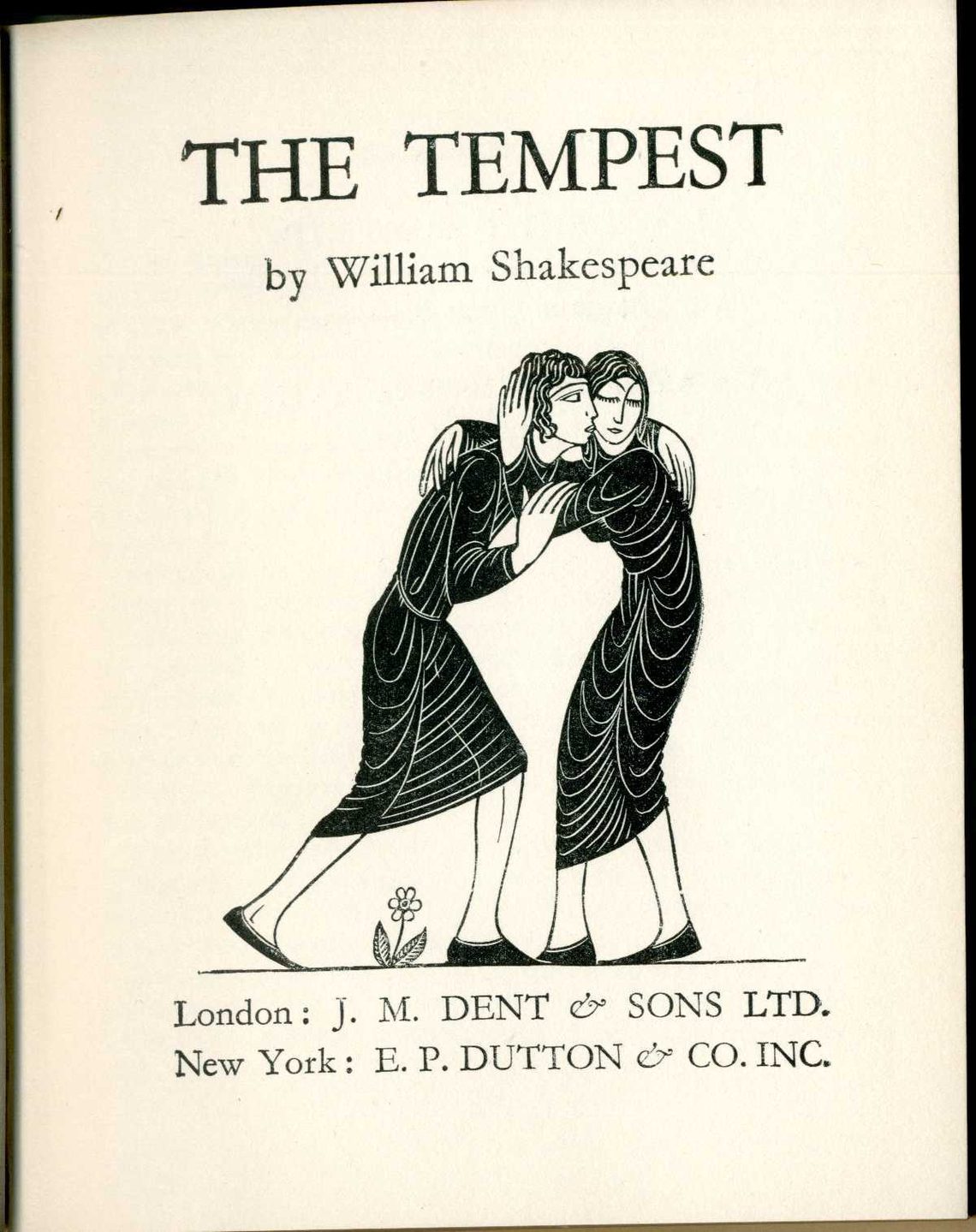

Britten and Pears’ copy of The Tempest, with design by Eric Gill.

During the mid-1950s Gielgud discussed with Peter Brook a possible production of Shakespeare’s The Tempest. He wrote to Britten proposing the idea that he write the incidental music. Shakespeare drew both men to work together in 1961 when Gielgud directed Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream at Covent Garden. As a tale of exile, suspicion, supernatural characters and of, course, the sea. It could be said that The Tempest contained all the ingredients certain to engage Britten’s interest.

And it did. In those early letters of the fifties Gielgud offered initial suggestions to Britten about music for masques and storms to which Britten responded enthusiastically. As time went on neither the play nor the music materialised although discussion continued in the background. In slightly later correspondence the actor stated that circumstances had changed slightly. He was now talking to Michael Powell about the play. Rather than putting it on stage, Powell was keen to make a film. Powell’s participation fell by the wayside, but In November 1965 Gielgud wrote excitedly to Britten about the possibility of Orson Welles taking on directing duties. In addition, he believed Welles would also be cast as Caliban. ‘I do believe THE TEMPEST properly done,’ wrote Gielgud ‘is the one Shakespeare play which lends itself outstandingly to the possibilities of the screen.’ Despite such eagerness both Gielgud and Britten discovered that other obligations kept them from getting round to working on The Tempest. And yet neither wavered in their desire to make the film.

By November 1969 Richard Attenborough had joined forces with Gielgud in The Tempest quest and Britten found himself corresponding with the tireless actor-director. Attenborough drew attention to the fact that finding financial backing for the project would be a challenge, but he informed Britten that adding his name to the list of creatives would show how serious an enterprise this was. The idea of working on the film still appealed to Britten but his own busy schedule had to be taken into account: he was committed to concert tours, and also had to devote time to writing his television opera Owen Wingrave, which Attenborough’s brother David had commissioned for BBC2. The innovative idea of setting the enchanted isle in the Far East had also emerged by this point. Filming in Japan was being mooted. It was an idea that was bound to appeal to Britten who had been inspired previously by traditional Japanese Noh Theatre for his Church Parable Curlew River. His 1957 ballet The Prince of the Pagodas—a story drawn from Eastern and Western (including Shakespearean) influences—had interpolated the sounds of the Indonesian Gamelan. Perhaps similar inspiration would have found its way into The Tempest soundtrack.

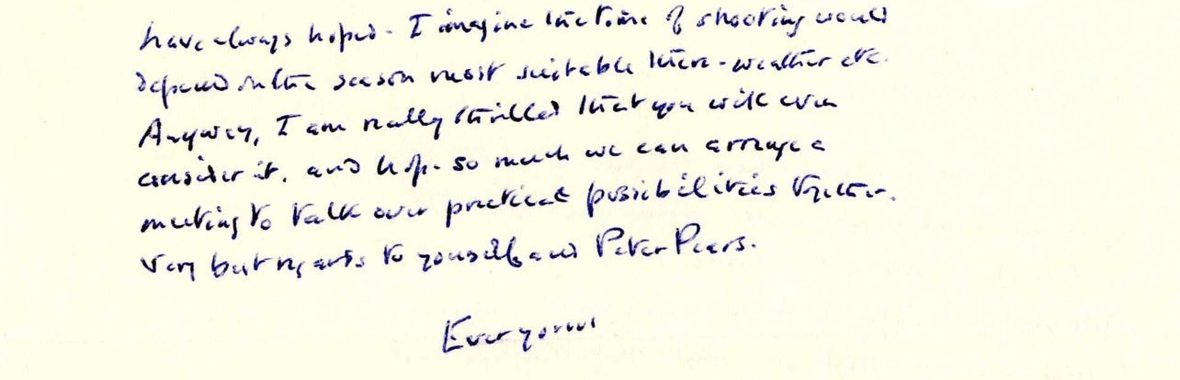

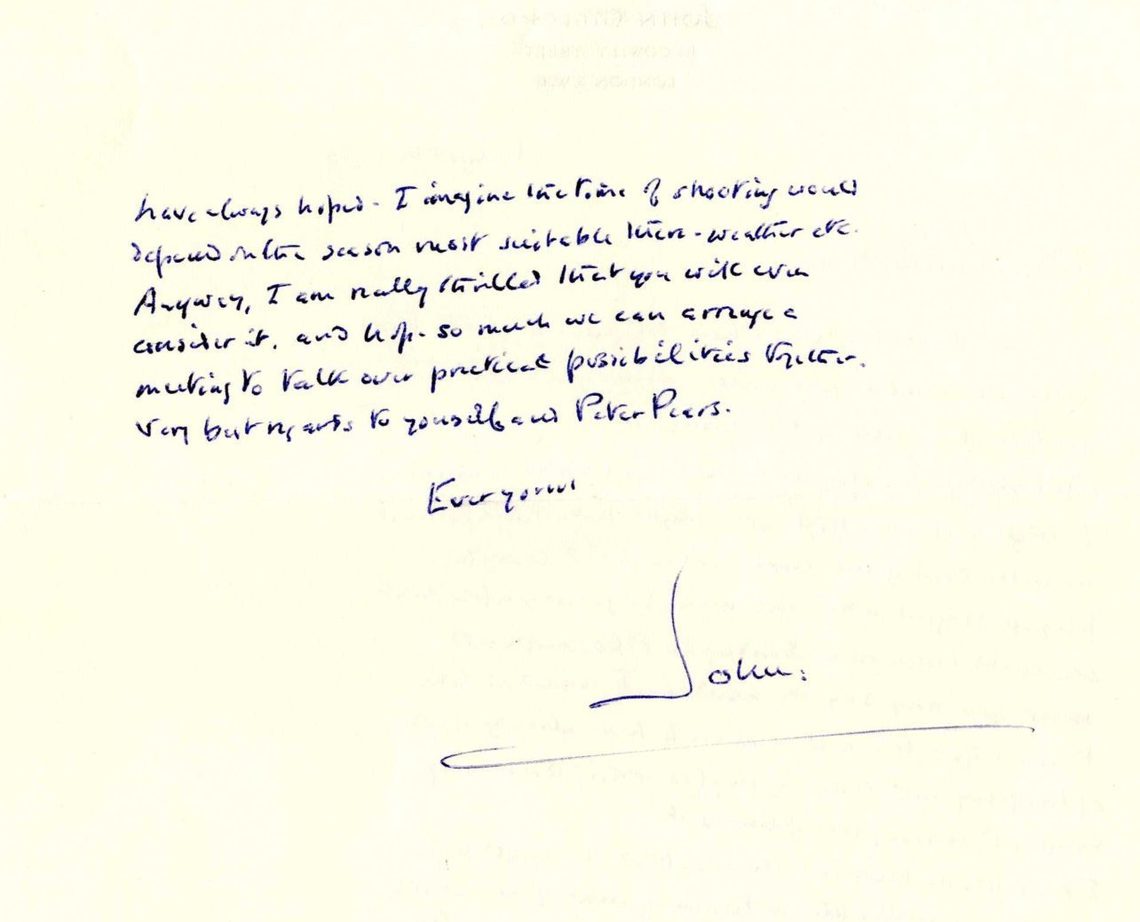

John Gielgud’s letter to Britten of 1969, in which he mentioned the idea of filming in Japan.

By January 1970 Paramount Pictures was showing interest. There was even discussion at this stage about eventual publication of the score. In July 1972 a potential new collaborator, the American actor and producer Chandler Cowles, joined the team. However, shortly thereafter Britten’s publisher Donald Mitchell informed Attenborough that a ‘very real problem’ was becoming apparent in the form of the composer’s ill health. This hadn’t diminished Britten’s willingness but yet another major concern was that he was trying to finish a new opera for the 1973 Aldeburgh Festival. It was something of a race, as the heart condition to which Mitchell alluded was sapping Britten’s physical and creative energies.

Fate finally cast its shadow over The Tempest when at the end of 1972 it was reluctantly agreed by all parties to abandon the project. Attenborough’s commitment was, as it had been for some time, now focussed on his goal of making a biopic about Mahatma Ghandi. Britten, as we know, was completing Death in Venice, and was also preparing for the surgery that would hopefully restore his rapidly failing health. Gielgud, however, eventually realised his wish by appearing as the exiled Duke in Peter Greenaway’s 1991 screen adaptation of the play, Prospero’s Books (featuring a score by Michael Nyman).

It is regretful that we don’t have ‘the strange sounds and sweet melodies’ of what would have been a fascinating Britten soundtrack, indeed a fascinating film version of Shakespeare’s play. But our correspondence collection provides full insight as to why it never happened.

- Dr Nicholas Clark, Librarian