In 1965 film director John Schlesinger approached Britten to supply a soundtrack for what would become a film classic. The composer’s reluctant decline provided an opportunity for one of his most gifted followers. The Archive tells their story.

‘Dear Mr Britten, I hope you will forgive me for writing to you out of the blue like this.’ This polite self-introduction opened a letter Britten received in the autumn of 1953. It was from a composition student who was embarking on his first term at the Royal Academy of Music. ‘I wondered,’ he continued, ‘if you could possibly spare a minute to glance at this score of mine and tell me what you think.’

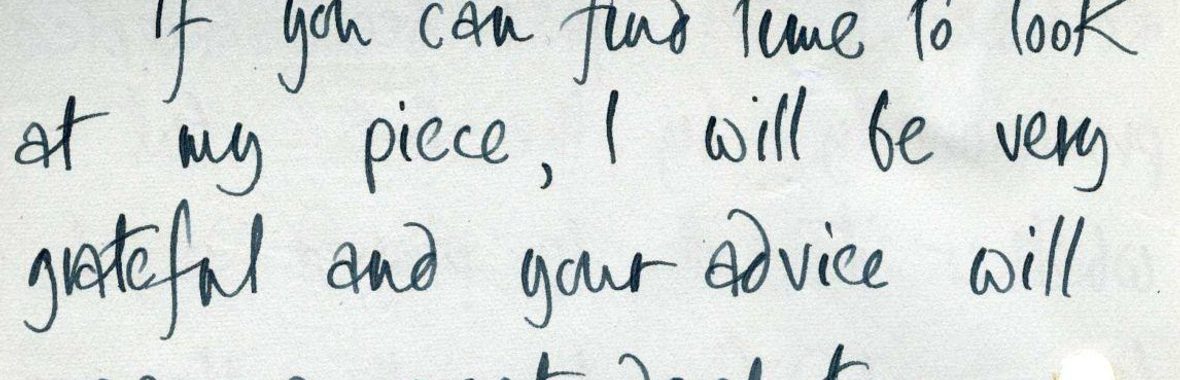

Our correspondence Archive contains a number of similar requests from composers who were keen to gain Britten’s opinion of their work. Very few, however, would go on to fulfil the promise that the score (an oboe sonata) which accompanied this letter suggested. The request came from the seventeen-year-old Richard Rodney Bennett. Although only a first year student at the Academy, he had already had a number of his pieces performed. A string quartet was due to be premiered in November of that year, and the sonata he sent to Britten had been ‘accepted provisionally’ by the BBC.

The final page of Richard Rodney Bennet’s 1953 letter.

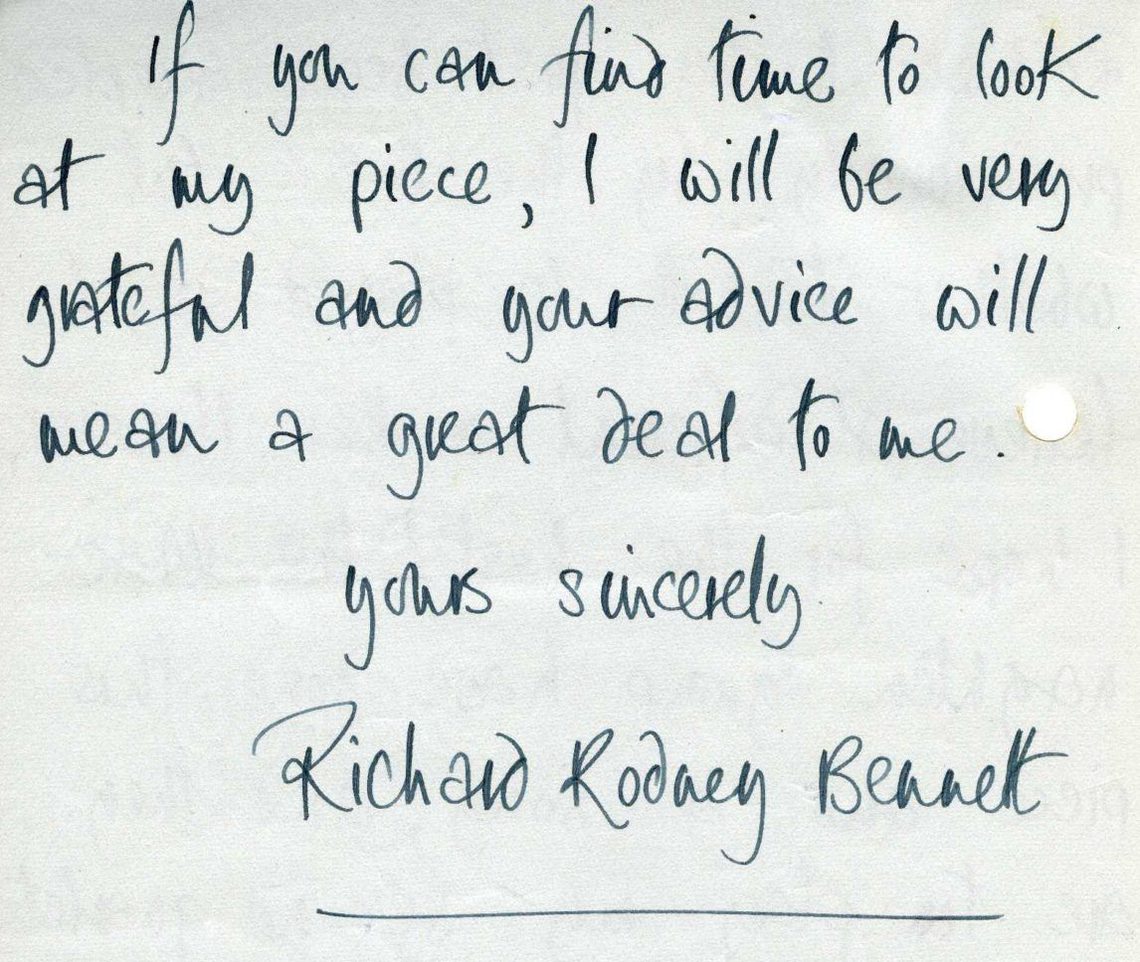

Bennett’s approach to Britten led to a lengthy friendship and a close artistic association with the Aldeburgh Festival. In 1963 he composed The Mines of Sulphur, tale that combined a theme of betrayal with the mystery of the supernatural. It was originally intended for the Aldeburgh Festival, but it received its first performance at Sadler’s Wells in early 1965. Bennett dedicated the opera to Britten whose initial response was, in all honesty, lukewarm. Still, he accepted the dedication and encouraged Bennett, believing opera was a field in which he would develop as a composer.

Programme for the first production of Richard Rodney Bennett’s The Mines of Sulphur, Sadler’s Wells, 1965.

Bennett’s prolific output went on to include opera, as well as vocal, choral music, orchestral and chamber music, concertos, and works for solo instruments. He mastered the idioms of serialism, popular song and jazz. The area of film music, however, has a special place in his oeuvre. And a Britten connection forms a link with one of his most accomplished scores.

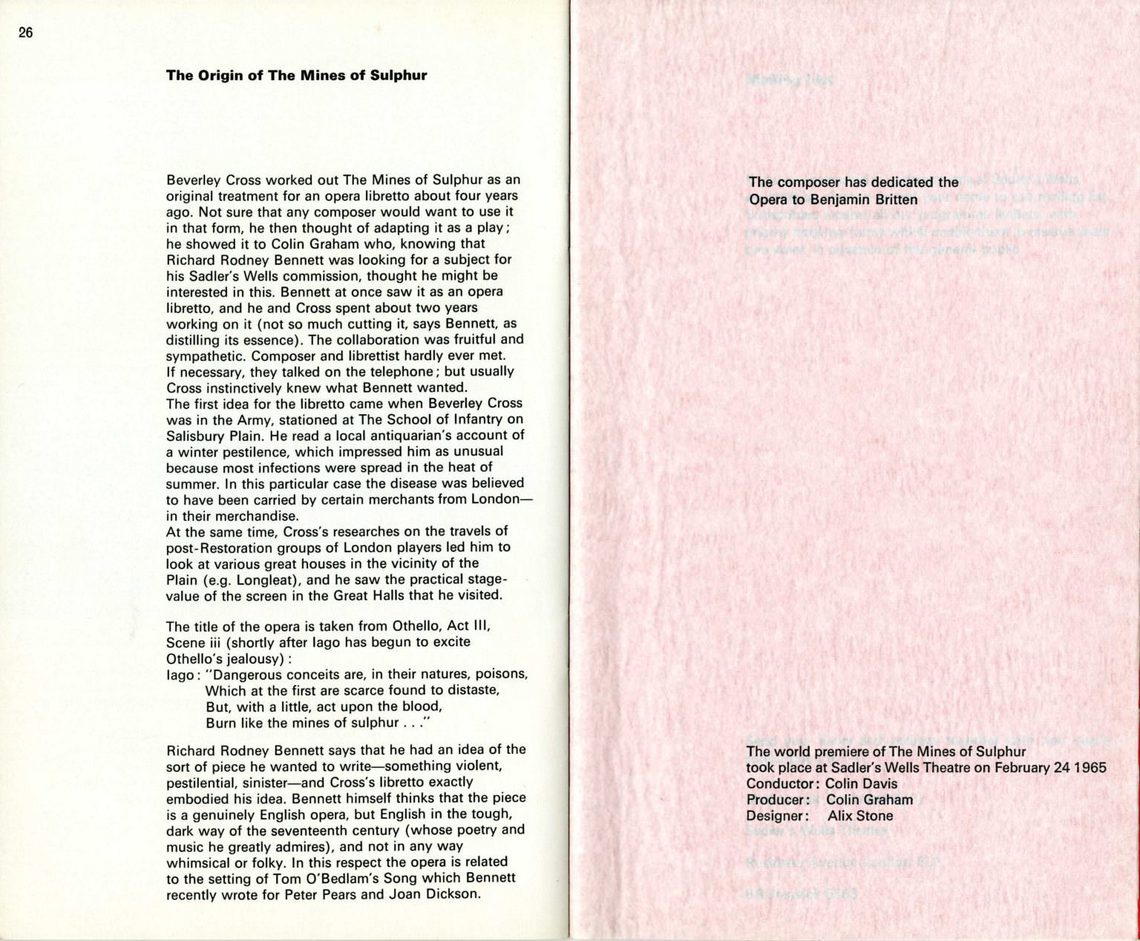

In 1965 the film director John Schlesinger was about to embark on a screen adaptation of Thomas Hardy’s novel Far from the Madding Crowd. Telling the story of Bathsheba Everdene’s choice between three very different men, the cast would feature Julie Christie, Peter Finch, Terence Stamp and Alan Bates.

One of Schlesinger’s first major jobs in television was a 1958 episode for the Arts series Monitor. His fifteen minute documentary chronicled the rehearsal process leading up to the premiere of Britten’s Noye’s Fludde. His footage of school children preparing for the opera’s premiere at Orford Church, and the composer’s commentary form a unique account of the Fludde’s making. Seven years later, as Schlesinger embarked on his cinematic version of Hardy, he began to consider the vital question of a soundtrack. He wrote to Britten, reminding him of the Monitor programme. With the knowledge that Britten used to compose film scores, he asked, ‘Quite simply would you consider writing the score for [Far from the Madding Crowd]? It is impossible to think of anyone else first.’

Britten was, as Schlesinger observed, no stranger to writing for film. He had supplied music for GPO documentaries, as well as the Anne Harding/Basil Rathbone feature film Love from a Stranger, during the 1930s. Significantly, the composer was a great fan of Hardy (as his library attests). He famously set a number of his poems in the 1953 song cycle Winter Words. The key requirement for Schlesinger was to capture character and landscape of a past time in rural England, which he believed Britten was fully able to do.

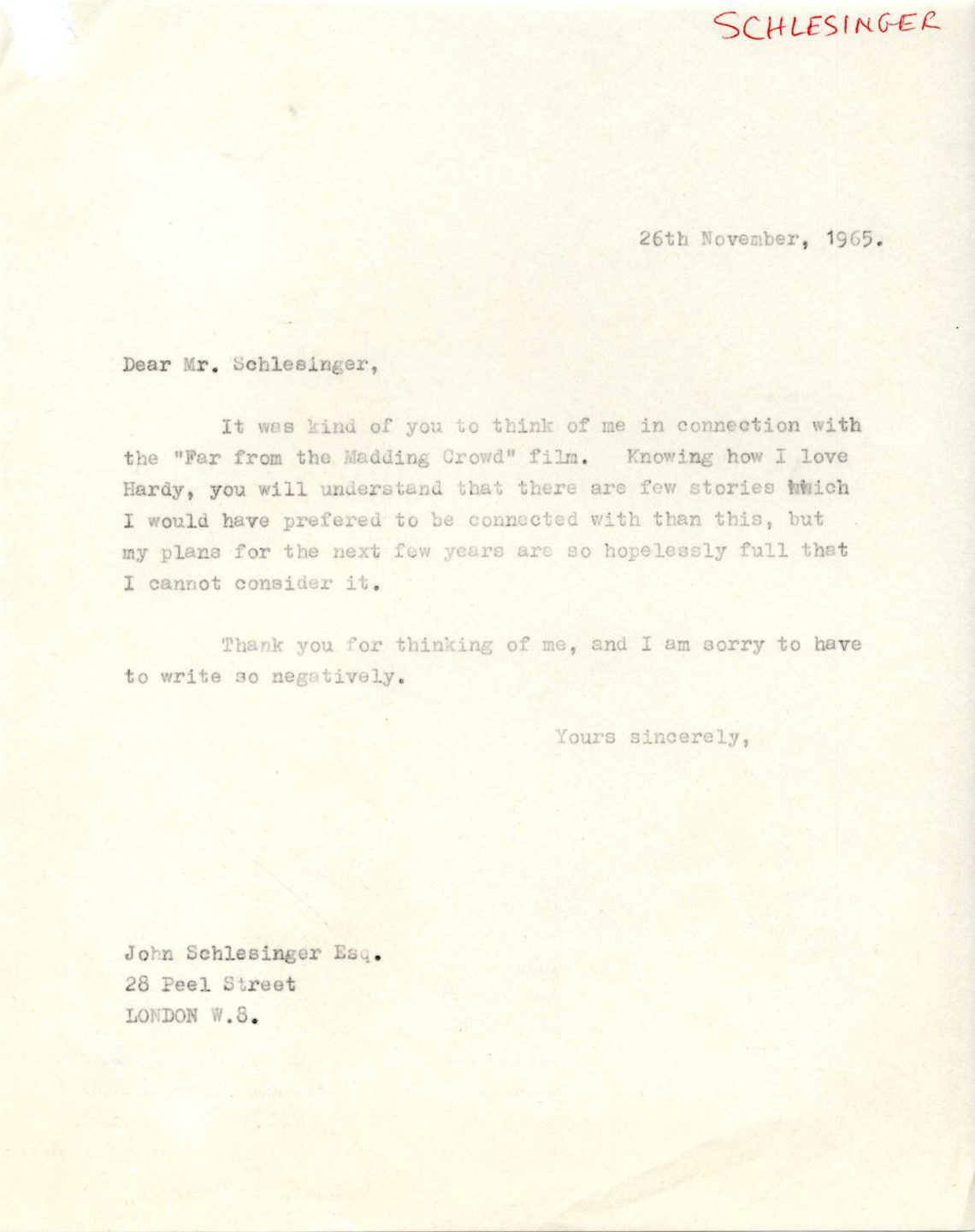

Britten’s reply to John Schelsinger.

Alas, as Britten stated by letter, he could not accept the commission. Eventually it was offered instead to Richard Rodney Bennett whose career had escalated since that self-introduction to Britten just over a decade earlier.

What we lost from Britten’s busy year was gained in Bennett’s soundtrack. He produced a score that caught the mood of Hardy’s Wessex perfectly. It conveyed a sense of the story’s characters and landscape. Bennett skilfully interwove folk music with lyrical themes that captured both romance and drama. It is one of Bennett’s most evocative film scores and deservedly garnered an Oscar nomination for the 1967 Academy Awards. It missed out to Elmer Bernstein’s Thoroughly Modern Millie, but this did not deter Bennett. Indeed, he went on to receive two further Oscar nominations, during a versatile and highly rewarding career.

Britten of course revisited Hardy in the 1974 orchestral Suite on English Folk Tunes, ‘A Time There Was… This may well provide an idea of what we might have heard had he been able to accept com Schlesinger’s commission. That notwithstanding, we have two excellent musical interpretations of Thomas Hardy, by two great composers. And the Archive partially explains how this came about.

- Dr Nicholas Clark, Librarian