Britten explained to his assistant Imogen Holst that the exuberance in the music he wrote for children arose from the fact that he was ‘still thirteen’. He looked back on his own childhood with great fondness. Some of the evidence for that nostalgia can be found amid his book collection. A number of the tales he kept even reflect interests that were later explored in his operas.

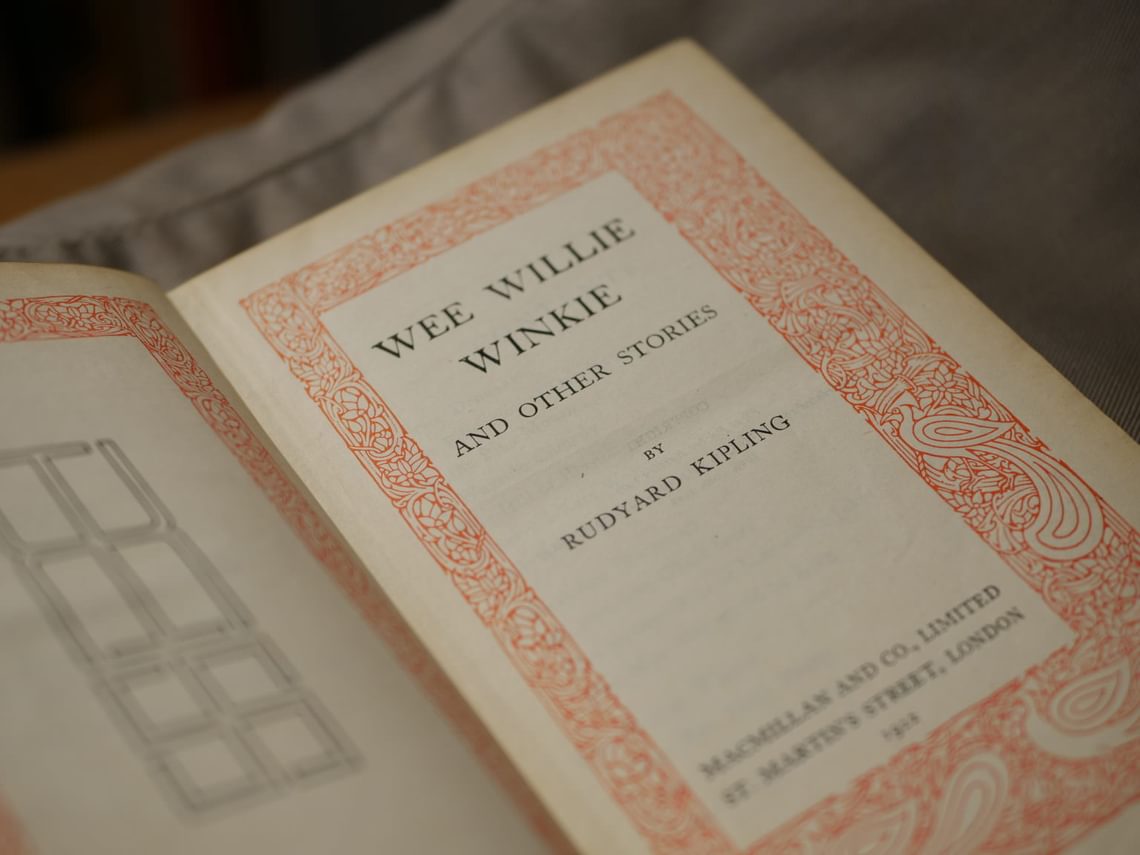

Title page for Wee Willie Winkie by Rudyard Kipling.

Indeed, one particular book may give us insight into the composer’s lasting interest in ghost stories, at least as far as some of the book’s content is concerned. At the age of eleven he was given a copy of Rudyard Kipling’s Wee Willie Winkie and Other Stories (Macmillan, 1922). It carries the inscription, ‘Edward Benjamin Britten, Xmas 1924, from E. H. Britten.’ ‘E.H.’ was from one of the future composer’s paternal uncles, Edward Horsnet Britten. ‘Edward’ was an established family name. Although Britten had taken to using his second given name at that stage it is little wonder that a namesake should insist on addressing him in such a way.

E.H. was clearly of the truism that most children enjoy a frightening yarn. The volume contains two of Kipling’s best forays into the supernatural, ‘The Phantom Rickshaw’ and ‘My Own true Ghost Story’. Brimming with atmosphere and creepiness, the effect these tales might have had were earthed by accompanying adventure stories for which the author was famous. Kipling of course has never been out of print and works such as his Just So Stories and The Jungle Books continue to enthral young (and young-ish) readers today, but in 1924 he was still living and producing more work. A complete set of Kipling from the original collection can be found in the Library.

Throughout his childhood books came to Britten from other family members. His copy of Charlotte M. Yonge’s The Little Duke, or Richard the Fearless (J.M. Dent, 1921) was given to him by ‘R. HM. B’ (Robert Harry Marsh), the composer’s brother. Stevenson’s Treasure Island (Cassell and Company Limited, n.d) was a gift from his sister Barbara in 1925. Both acknowledged classics, these and other titles in the collection provide insight into the type of reading that children undertook during this period.

Britten clearly retained a taste for childhood reading. For example, his enjoyment of Arthur Ransome’s ‘Swallows and Amazons’ series is well known. So desperate was he for Ransome’s We Didn’t Mean to Go to Sea that at one point he swapped his composition draft of the newly completed cantata Saint Nicolas for a copy of the book!

Opening illustration of The House at Pooh Corner.

Britten’s friends appreciated his enjoyment of children’s literature. The first performance of the comic opera Albert Herring was marked by his receiving a copy of A.A. Milne’s The House at Pooh Corner (Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1946) with ‘decorations’ by Ernest H. Shepard.

Ben, In happy memory of the first première I have ever been to (of any kind) & with great gratitude, love, George [Harewood], 20th June 1947

Inscription from the Earl of Harewood to Britten.

The inscription provides information about the thirty-three year old composer’s reading tastes, and the Earl of Harewood’s first experience of a premiere.

One of many wonderful illustrations by Joseph Noel Paton.

Perhaps the most touching story connected with this collection of childhood reading is one that involves both Britten and Pears. In the mid-1970s, in the wake of Britten’s heart surgery, he would sometimes listen to Pears reading from Charles Kingsley’s The Water-Babies. Their 1879 copy of the novel with its evocative illustrations by the Pre-Raphaelite artist Joseph Noel Paton is well-foxed and shows every sign of having been read and re-read countless times. Britten would listen to the tale of Tom the sweep and his transformation into a water baby (perhaps recalling his own incarnation as a water baby) as told to him by Pears in the peaceful surroundings of The Red House drawing room. An exhausted Pears would sometimes fall asleep, having returned from touring, and the two would just sit quietly together.

Britten on his mother Edith’s knee during a Sparrow’s Nest Theatre, Lowestoft production of Kingsley’s The Water Babies, in which he played Tom, June 1919.

- Dr Nicholas Clark, Librarian