Festival Walks are still a fixture of today’s Aldeburgh Festival, but the Church Crawl has been left by the wayside. Church Crawls ran consecutively from 1969 to 1973. They were led by the historian Norman Scarfe, and they presented three churches through a “short programme of music and a descriptive statement about the architecture”. The crawlers were reminded in the programme to bring opera-glasses to fully appreciate the architecture. The Crawl would conclude with a drive back to Snape Maltings for tea.

Although unable to embark on a physical pilgrimage, the Britten-Pears Archive collection nevertheless enables an imagined meander through the Aldeburgh Festival’s most important churches. In this article, we venture to Holy Trinity Church, Blythburgh.

The 1956 Festival programme features an article on Blythburgh Church to coincide with the Church’s first appearance in the Aldeburgh Festival. Ronald Blythe, who in 1956 was working as the Festival’s assistant secretary, writes in his article that Blythburgh Church was “built mainly in the fifteenth century in that wave of strenuous piety and unfounded optimism with which the Middle Ages closed”. One of the most significant events in the Church’s history occurred during morning service in August 1577. A thunderstorm was rolling through the village when lightning struck the church steeple, causing the spire to crash through the roof. From this point onwards the church suffered a long period of neglect. So much so that by the 19th

century “rain [would] beat down steadily through the painted roof and poured off the angels’ wings”. In appearance, the church has been “blanched by the East Anglian climate. Inside it is pale and faded as though drenched in centuries of fine, marine light”.

Nikolaus Pevsner. The Buildings of England: Suffolk. Penguin Books, 1961

This is formally presented in Britten’s copy of Pevsner’s The Buildings of England: Suffolk. It contains the expected inventory of the church’s furnishings, and Pevsner concedes that Blythburgh is “one of the half dozen grandest Suffolk churches […] with its bare white interior”. Like Blythe, Pevsner mentions the angels of Blythburgh. He writes “from the centres of the tie-beams and their bosses big angels stretch their wings”. Blythburgh once boasted twenty such angels, but now, after the spire took some of them with it, only eleven remain.

Blythburgh’s debut in the Aldeburgh Festival was, partially, the responsibility of Ronald Blythe. Blythe was interviewed as part of our Oral History Project. He recounted how:

“one day…Ben said, ‘Would you go to ask Mr Thompson, the vicar of Blythburgh, if we can have the church for a concert?’ […] I went on a bus, and it was very hot...And this old gentleman, although Aldeburgh was just down the road as it were, he said ‘What kind of thing is it? Is it a band?’ I said’ Sort of’’ so he said that we could have the church. And I said, because I daren’t go back without it all arranged, ‘But should you not ask your PCC?’ – whereupon he was in a rage with me at my daring to ask such a question. ‘I do what I like here’ sort of thing. So, I went back and told Benjamin Britten that we could have the church. […] So many people came on a hot day and sat on the tombs outside; it was lovely.”

From 1956 onwards, Blythburgh became a frequent, and well-loved, Festival venue, but it was during the 1969 Festival that Blythburgh would have a special role to play.

For context, Snape Maltings Concert Hall had opened in 1967 and had become the epicentre of the Aldeburgh Festival’s programming. Two years later, on the opening night of the 1969 Festival, a fire broke out. Caused by an electrical fault, it completely destroyed the concert hall.

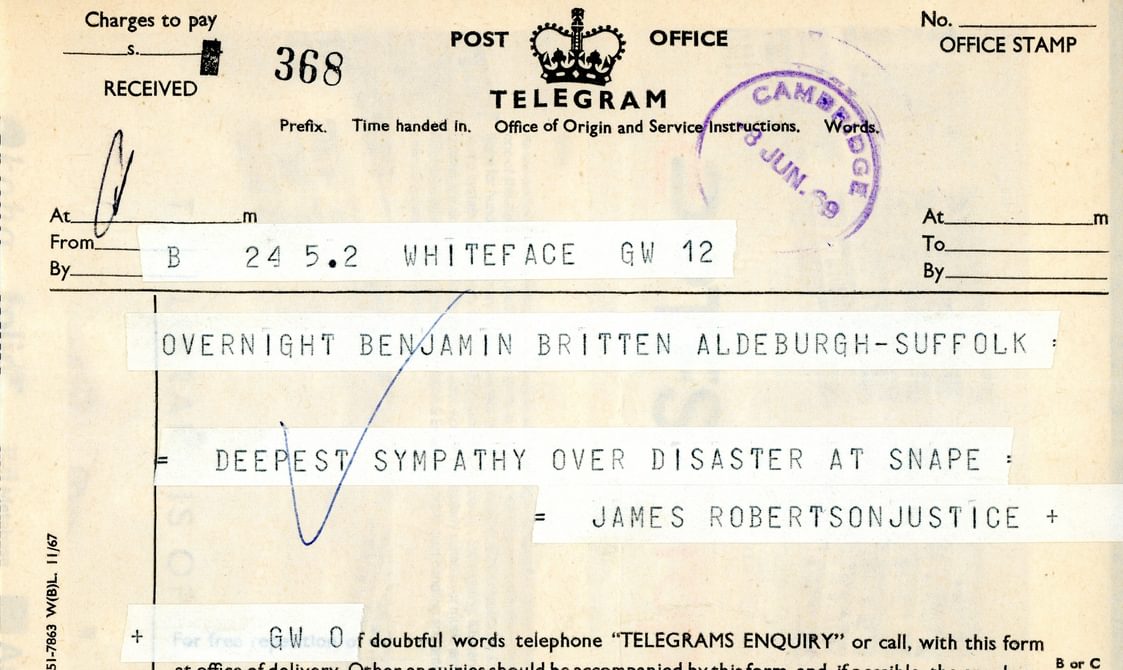

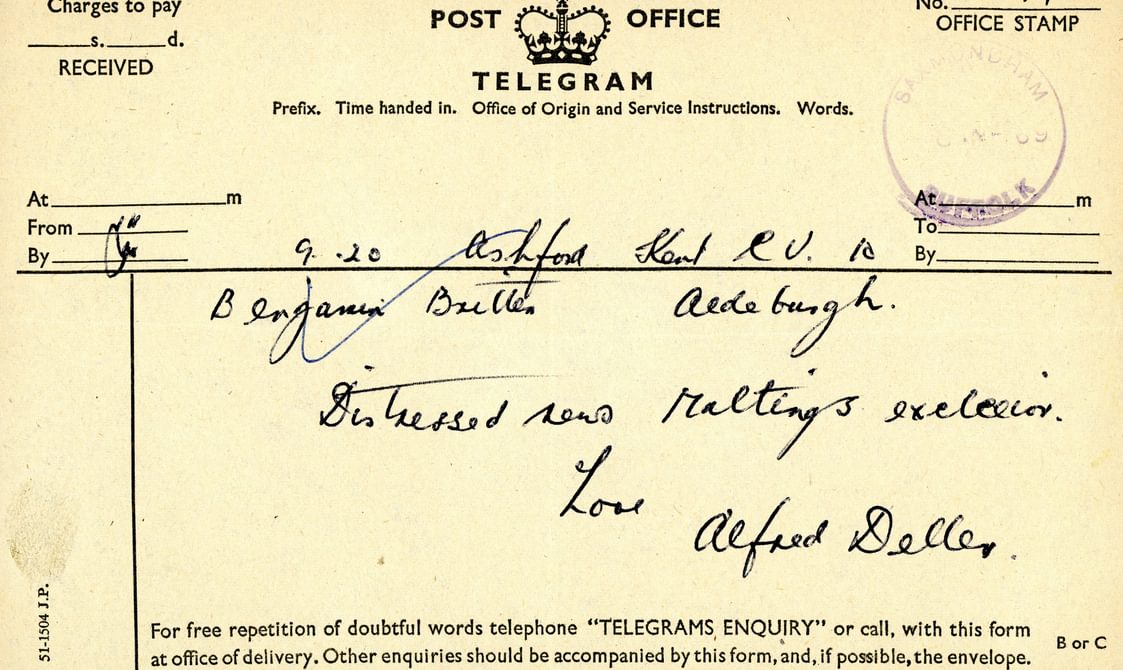

We have documented the administrative history of this event. We have a visual record of it, alongside correspondence, meeting minutes, and fundraising appeals. Within these files, are the dozens of sympathy telegrams that the organisation received, including telegrams from individuals such as Yehudi Menuhin, John Gielgud, Alfred Deller, James Robertson Justice, and David Attenborough.

Image gallery

A gallery slider

Telegram from James Robertson Justice

Telegram from Alfred Deller

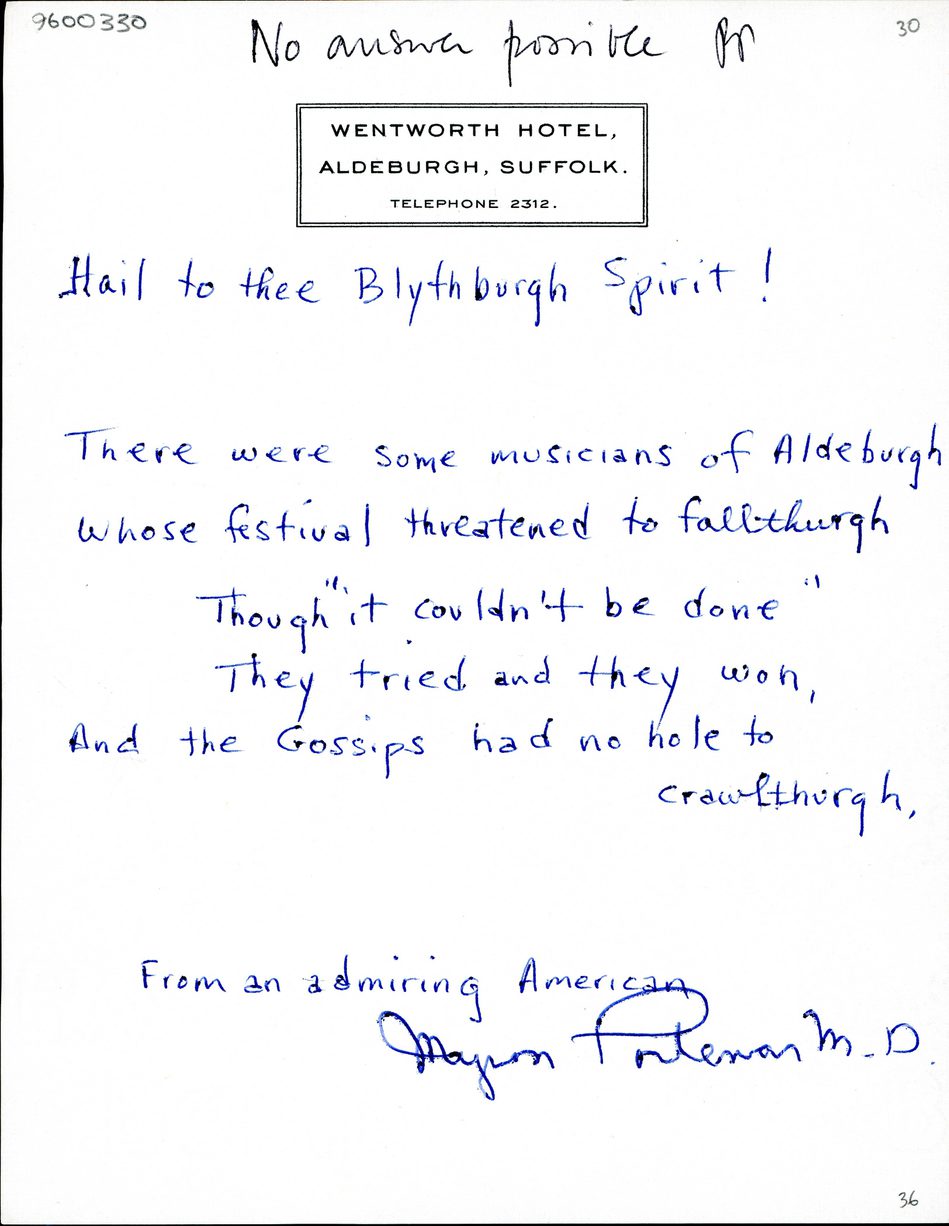

The entirety of the 1969 Festival still lay before them and a decision had to be made on the Snape Maltings concerts. Most importantly, Mozart’s Idomeneowas scheduled to be performed on June 10, only three days after the fire. Amongst the telegrams, there is a letter from ‘an admiring American’ which reveals the Festival’s solution.

Letter sent to the Aldeburgh Festival after the fire at Snape Maltings

It reads:

Hail to thee Blythburgh Spirit!

There were some musicians of Aldeburgh

Whose festival threatened to fall through

Though “it couldn’t be done”

They tried and they won,

And the Gossips had no hole to crawl through.

It was decided that Idomeneo, along with many other concerts, would be moved to Blythburgh and a revised programme for Idomeneo was quickly distributed with reduced audience numbers.

Image gallery

A gallery slider

Photographs of performers, including Peter Pears, outside Blythburgh Church.

Credit : Brian Simpson

Photographs of performers, including Peter Pears, outside Blythburgh Church.

Credit : Brian SimpsonThe move necessitated the building of a stage around the Church’s font. The audience was crammed into the church, seated facing away from the altar with their legs through the backs of the pews. But by all accounts, Idomeneo survived its relocation and was a great success.

Beyond the Festival, the Archive holds art and poetry relating to Blythburgh.

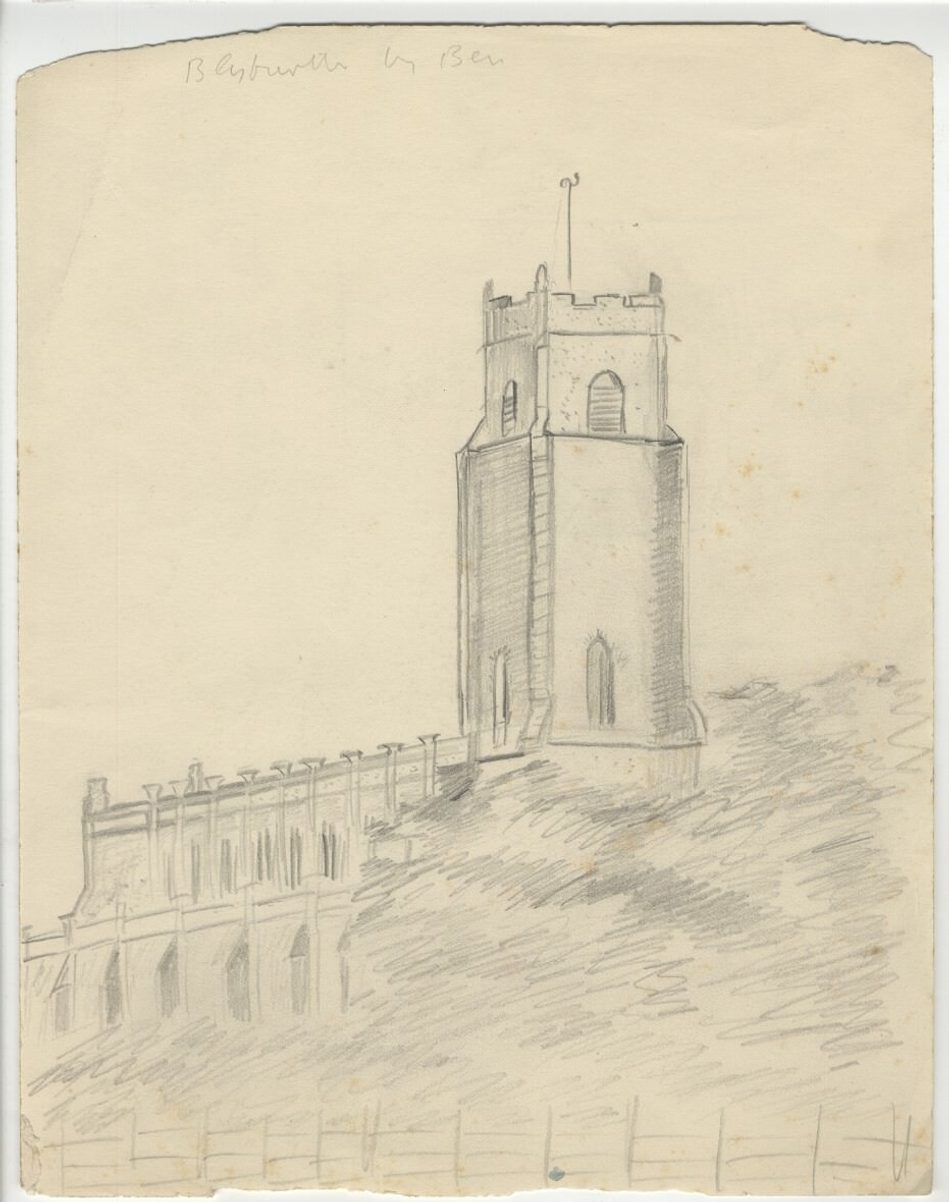

Pevsner described the tower of Blythburgh as “impressive enough when seen across the creek”. We can see this vantage point through the eyes of Britten himself. In the 1950s, planted in the shadow of Blythburgh, Britten and Pears had a sketching lesson with Mary Potter. This excursion proved fruitful with Britten committing several pencil sketches of Blythburgh to paper.

‘Blythburgh by Ben’ by Benjamin Britten

To pluck another work from the art collection, we have ‘Roof. Blythborough Church, Suffolk’ which gives a visual to these omniscient angels of Blythburgh (see above).

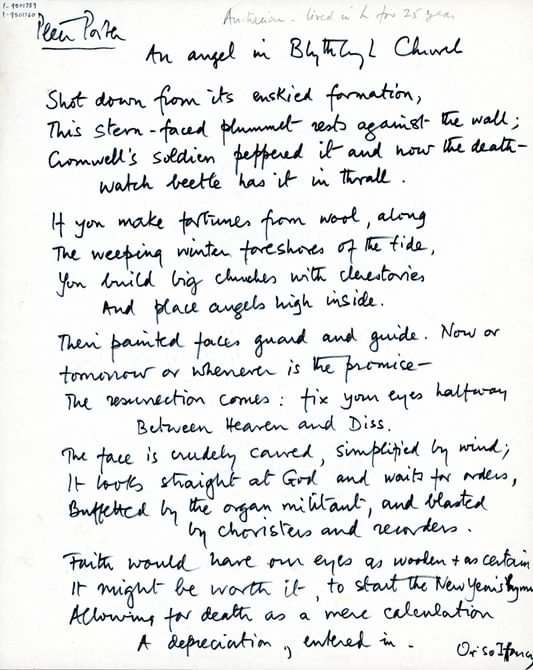

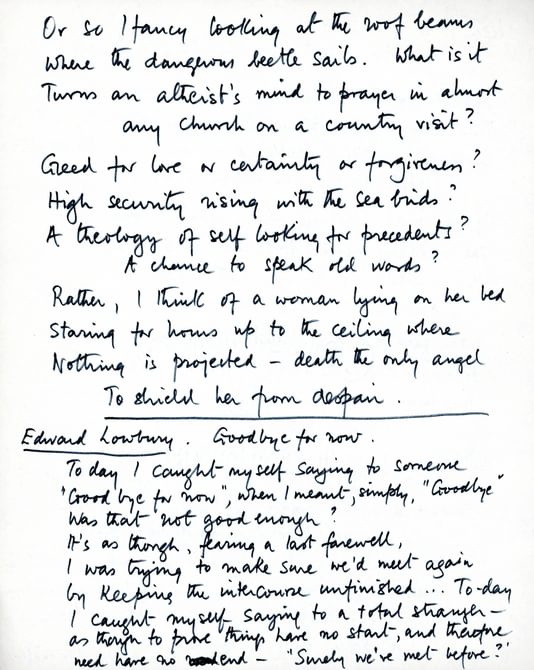

Britten and Pears were avid readers of poetry, evinced by their extensive poetry collection. We can construct their reading habits from their library and, extraordinarily, from the papers that they had laying on their desks. Pears purchased Peter Porter’s Collected Poems (1983) and from this volume Pears singled out the poem ‘An Angel in Blythburgh Church’. We know this because, at some point, Pears chose to copy it out in his own hand on a scrap of paper. This piece of paper was then transferred to the Archive when the downstairs study in The Red House was cleared in 1993. It could easily have been discarded, yet it exists as though only just taken from his desk.

Image gallery

A gallery slider

Peter Porter’s ‘An Angel in Blythburgh Church’ handwritten by Peter Pears

Peter Porter’s ‘An Angel in Blythburgh Church’ handwritten by Peter Pears

Through Pears’ scrawl, we can read as Porter weaves together the Church’s history with the mythology that surrounds it, but, of the angels of Blythburgh, Porter writes:

…Their painted faces guard and guide. Now or

Tomorrow or whenever is the promise –

The resurrection comes: Fix your eyes halfway

Between Heaven and Diss…

Sascia Nieuwenkamp, Archive Trainee

Header image: ‘Roof. Blythborough Church, Suffolk’, unknown artist

You might also like

Archive Treasures: The story of a Holocaust survivor and a musical legacy

We mark the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II, and of the liberation of the death camps with the story of a special…

Archive Treasures: Armenian Amphora

Among the many treasures on display at the Red House is the splendid Armenian amphora. It dates from the Urartu era, a civilization which, from the…

Archive Treasures: The English Opera Group

The English Opera Group collection forms part of the Britten Pears Arts Archive which documents the lives and work of Britten and Pears, as well as…