In the archive at the Red House, there is shelf after shelf of Benjamin Britten’s correspondence: its cataloguing was recently completed by a team of volunteers, after which the final total stood at over eleven thousand files. Much of it is professional and there is also personal correspondence such as the intimate, affectionate letters that Britten and Peter Pears exchanged when the two men were apart. It also reflects the wide range of Britten’s activities beyond his musical career, and in particular his active engagement with a wide variety of social issues.

Britten’s pacifism is well-known, his horror of violence informing works such as the War Requiem and Owen Wingrave. His commitment, however, was not limited to this: his correspondence reveals engagement with a huge range of campaigning causes, one of which forms the focus of this article.

Nelson Mandela is, of course, a household name now: the Nobel Peace Prize winner who helped to negotiate the end to apartheid in South Africa and who led the country into its post-apartheid future as its first president to be elected in a free, multi-racial election. Before his release from prison in 1990, Mandela and his long imprisonment on Robben Island symbolised the apartheid regime for a generation of campaigners, with streets, parks, leisure centres and student common rooms all being named or renamed after Nelson Mandela to raise consciousness of the reality of apartheid. Documents in the archive, however, take us back to the start of that long imprisonment, to 1963 when Mandela was one of a large group of militants on trial following their capture in the Johannesburg suburb of Rivonia.

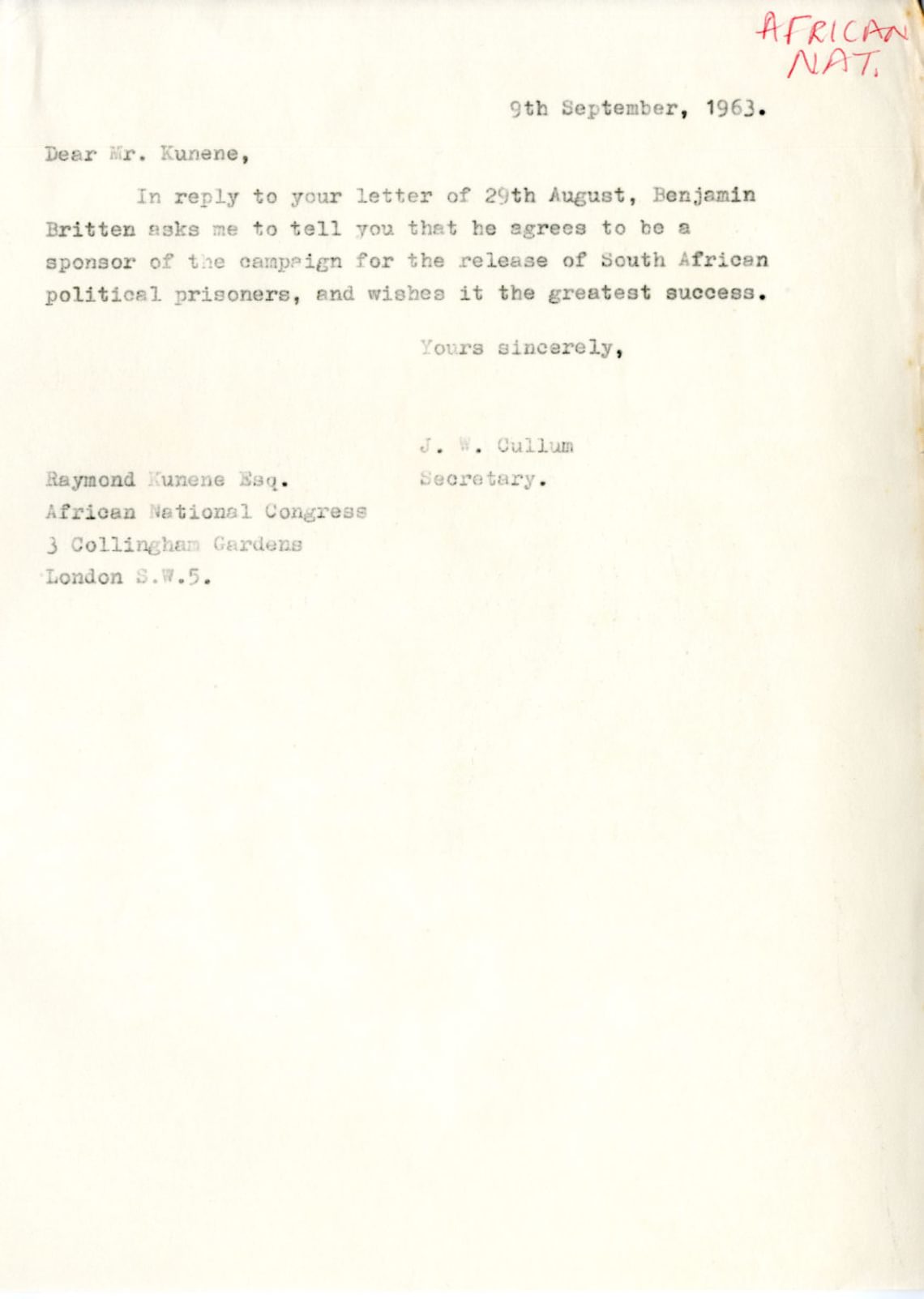

Britten’s reply (via secretary Jeremy Cullum) to the African National Congress confirming his support.

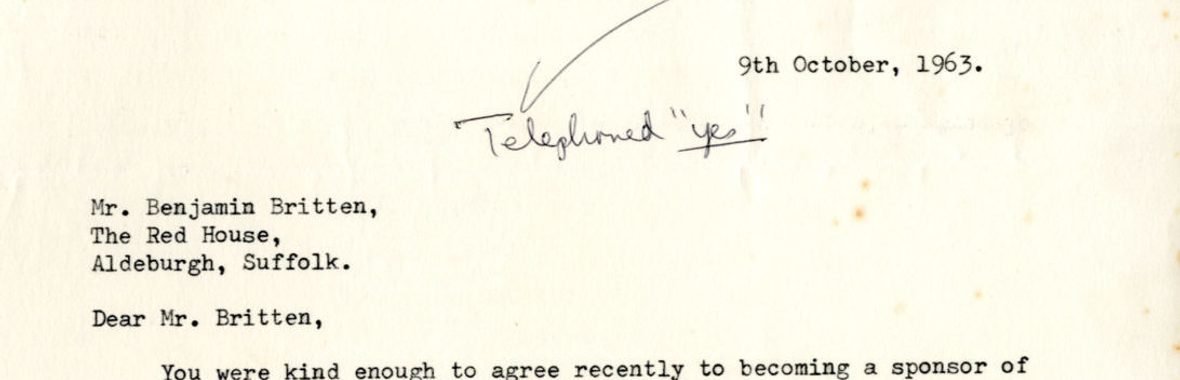

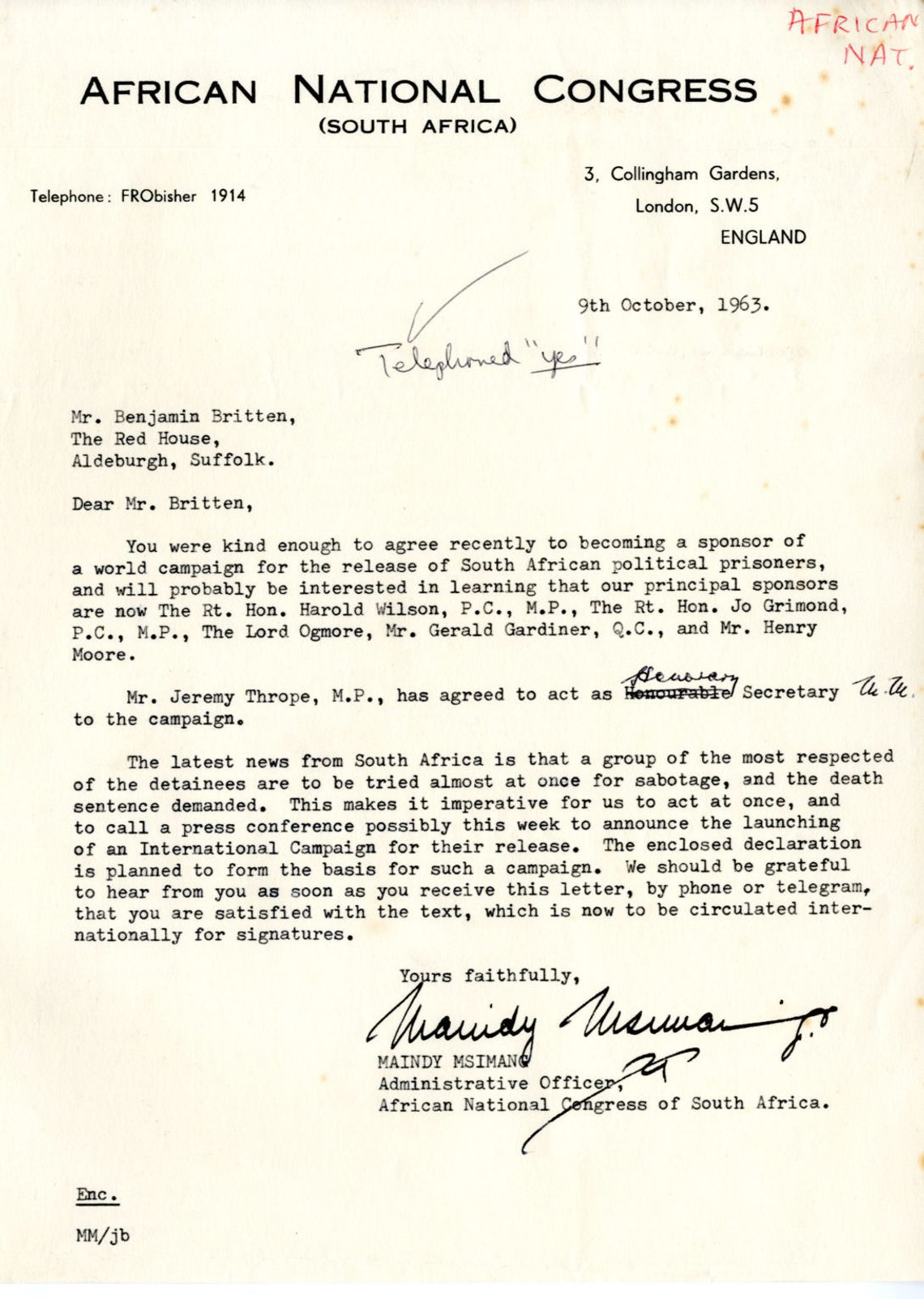

In August that year the African National Congress – the freedom-fighting organisation to which Mandela belonged and which he was to steer into government decades later – wrote to Benjamin Britten, setting out their plans to press for the release of these anti-apartheid activists, who faced a possible death sentence or life imprisonment. The campaign needed sponsors to act as its figureheads, these being “people of international reputation”; the ANC listed some of the people already filling that role, among them the future Prime Minister Harold Wilson. Britten, as his record of political activism would suggest, signed up quickly. A few weeks later the ANC contacted Britten with the text of a declaration that was to form the basis of its campaign, asking Britten if he was happy to be a signatory to it, and here we see something typical of Britten’s political campaigning: the file does not contain a letter back from him but instead, on the ANC’s own letter, there is a quick scribble in Britten’s distinctive hand saying simply “Telephoned ‘yes’”.

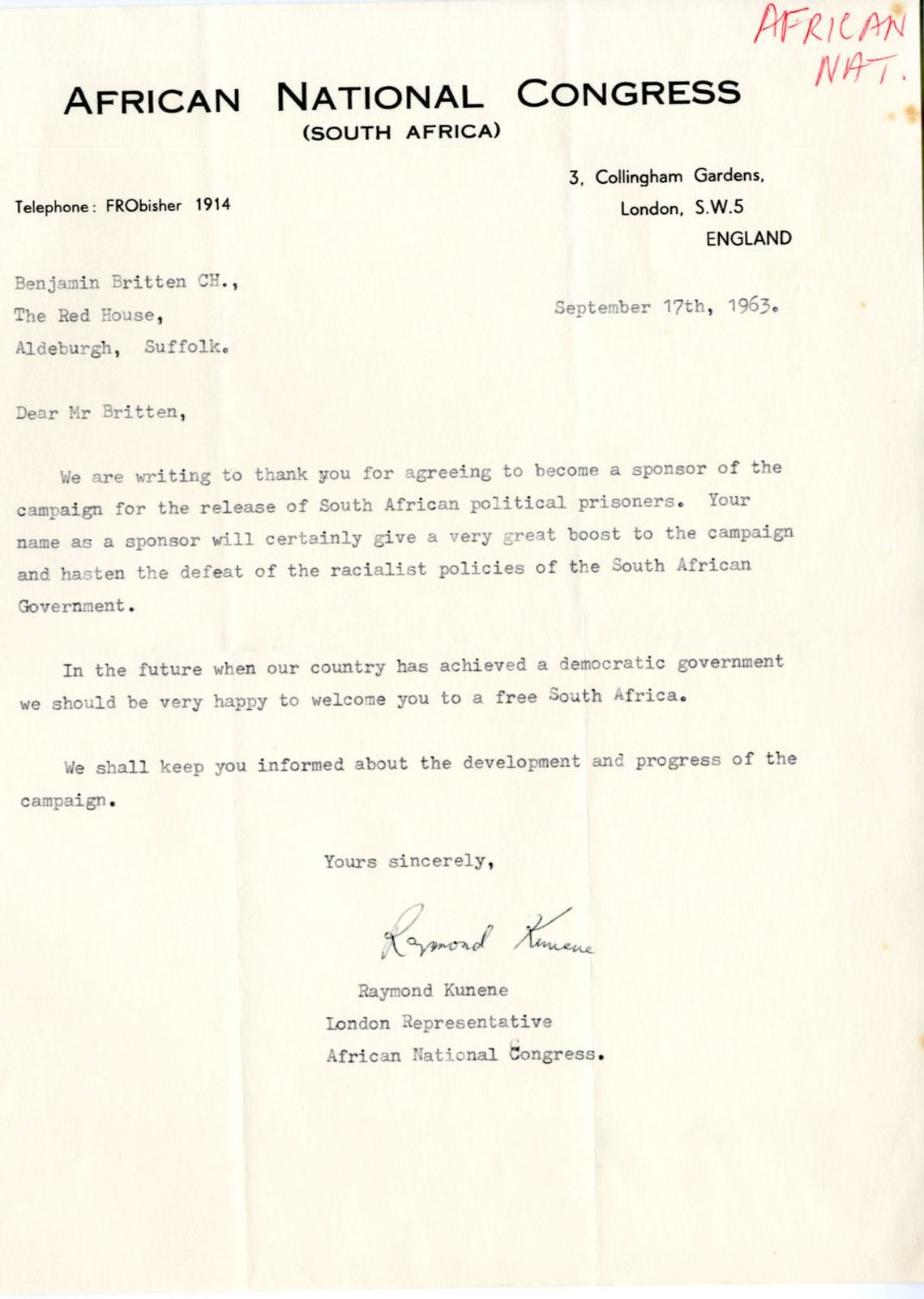

When Britten first signalled his willingness to support the ANC campaign, their London representative wrote to him “In the future when our country has achieved a democratic government we should be very happy to welcome you to a free South Africa.” As we know, Mandela and his colleagues were convicted: the death penalty was not applied, but most spent many years in prison. Britten had been dead for over thirteen years by the time Mandela was released. He would not see the end of apartheid but in line with his ideals, he had done what he could during his time, and handed the baton on to the next generation. This one file, among thousands in the archive, ties Britten into one of the major political stories of his generation.

The correspondence can be seen in the collection of correspondence relating to Britten’s various sponsorships, at https://www.bpfcatalogue.org/archive/BBS-AFRICA_CENTRE

- Dr Christopher Hilton, Head of Archive and Library