The former homes of famous people are referred to, variously, as ‘house museums’ or ‘personality houses’. They are effectively physical ‘biographies’, telling the stories of the well-known former occupant(s) and presenting the physical traces of their habitation to the visiting public. In the case of The Red House in Aldeburgh, Britten and Pears’ final home, the physical traces are abundant and always evocative to those who visit. The house reflects the personality of those who lived there; but it also retains a strong personality of its own. It is a former farmhouse developed and added to over centuries, with multiple nooks and crannies, two staircases, and a rabbit warren of corridors; it has an eclectic jumble of furniture, brightly coloured carpets, vast numbers of books on myriad subjects, and an astonishing art collection; and sits within a 5-acre plot with an orchard and lawns for tennis and croquet, plus two small bungalows on its outskirts. As such, the house is inherently intriguing, even without knowledge of its famous former residents.

The Red House, photographed in October 2020 (Photographer: Beki Smith)

Letter from Britten to Princess Margaret (‘Peg’) of Hesse and the Rhine in early 1958, using leftover headed paper from the previous house.

For Britten and Pears, who moved there in 1957, the house was their retreat. Even before they moved there, this was literally the case, but when they became the occupants themselves it became even more so, especially for Britten. The property as a whole, later on including the Studio, the Library, and offices for his staff, was arranged to suit his preferred mode of working, as well as to support his immensely busy schedule of composing, rehearsing, and administering the Aldeburgh Festival. He composed in the Studio from mid-1958, which was a converted hay-loft with stunning views of what would have been open countryside at the time; and would rehearse in the Library, constructed in 1963, and substantial enough to house his Steinway D piano. The Red House as a whole became a self-sufficient operation, enabling Britten to remain in Aldeburgh as much as possible.

The Steinway ‘D’ grand piano in the Library (Photographer: Beki Smith)

The Steinway ‘C’ grand piano in the Studio (Photographer: Beki Smith)

While Britten and Pears both travelled a great deal, giving tours across the world, Pears was often away from home by himself: letters between the couple show the extent of his solo travel over the years. As such, the couple were somewhat divided in their approach to and feelings about ‘house and home’. Hermione Lee discusses whether there a meaningful distinction between the actual terms ‘house’ and ‘home’ in a recent edited book of essays, The Lives of Houses:

‘House’ and ‘home’ notoriously make awkward neighbours. Sometimes the words invite each other in; sometimes they won’t give each other the time of day. Dictionaries and books of proverbs and old sayings tell you different things.

Preface to The Lives of Houses edited by Kate Kennedy and Hermione Lee, p. xiv

https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691193663/lives-of-houses

But in the case of Britten and Pears they may provide a useful distinction. For Pears, perhaps the ‘house’ was most important: he was certainly more involved in decoration, choosing carpets in his favourite colours of red and green for the Red House. Such ‘nesting’ aside, he was a more itinerant figure, not so physically attached to a location, although particular about its aesthetic; and needing more of a metropolitan ‘fix’ than Britten.

For Britten, ‘home’ was key: the sense of security, and the need to be absolutely rooted in one geographical area. In a chapter on Britten and Aldeburgh in The Lives of Houses, Lucy Walker writes:

The first home he purchased in Snape (The Old Mill) was a welcome respite from the busyness and emotional complications of his London life. His coastal homes (in Lowestoft, and Crag House in Aldeburgh) met a powerful need to have regular contact with the sea. … [While living in the USA from 1939-42] his letters to family and friends back in the UK are shot through with longing . . .and to his friend Enid Slater a heartfelt desire to see Suffolk again (‘It pleases me to hear you talk about Snape & Suffolk . . .I’ve been horribly homesick for it recently’). A brief stay in a bohemian household in Brooklyn [which included WH Auden and Gypsy Rose Lee] further helped Britten realise what he did not want from a domestic space.

From ‘Benjamin Britten in Aldeburgh’ by Lucy Walker, in The Lives of Houses, p. 110.

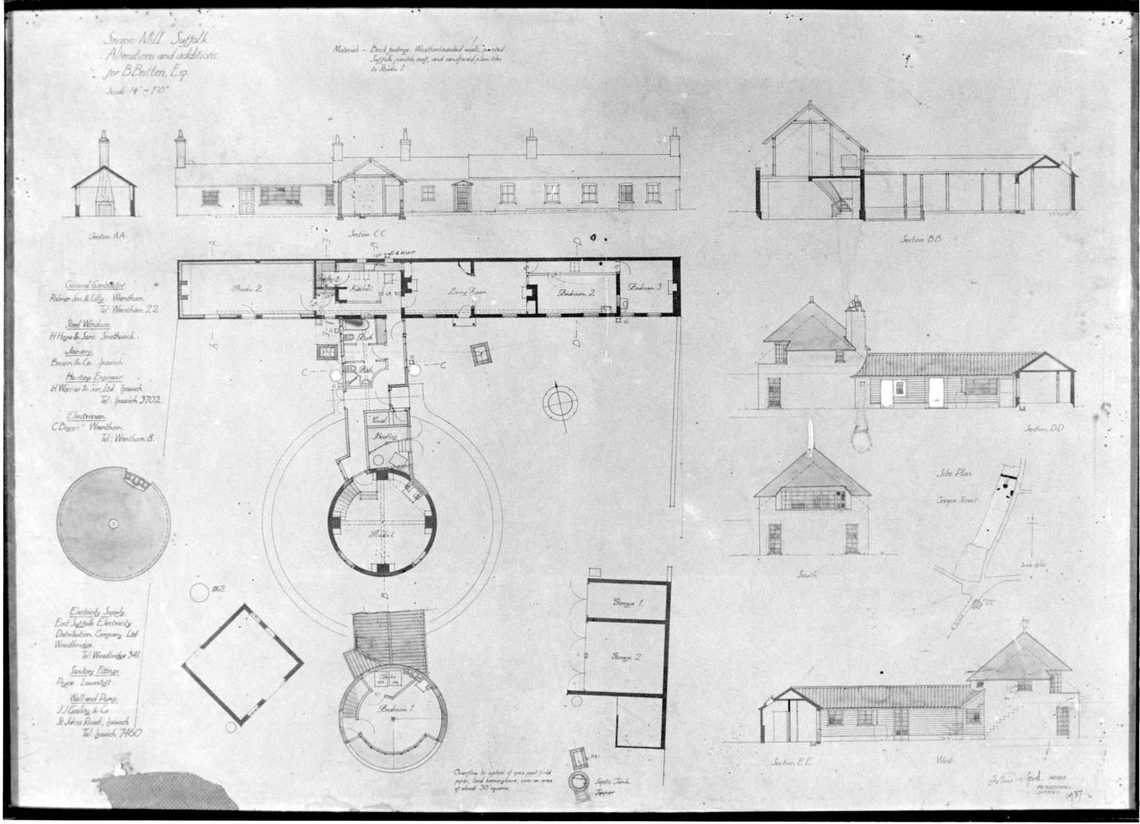

Britten was not uninterested in his home’s interiors (writing to Pears about Crag Path, ‘The walls will be white with an offness of pink’) and was keen on architectural innovation. When he bought The Old Mill in Snape he was very much involved in its conversion (carried out by Arthur Welford, his sister Beth’s future father-in-law) and together they designed what was a very modern structure for its time. But above all, it seemed he needed to be secure in his domestic setting – to inhabit a ‘warm nest of love’ as WH Auden sarcastically put it to him once.

Architectural plan for the conversion of The Old Mill, Snape in 1937

It may seem surprising that two men could live together so peacefully in the 1940s onwards given the laws and general public perception of homosexuality of the time. Britten and Pears’ life together was hardly a secret, but Aldeburgh appeared to acknowledge them as a couple: our Archive Treasures article ‘Love in the Accounts’ discusses the everyday acceptance in the town that they lived together, exemplified by that most humble of household of documents, a receipt.

Britten and Pears outside Crag House in summer 1957, a few months before moving to The Red House, with their puppy Jove (Photographer: unidentified)

A similar example can be found in WH Auden’s case, after he chose to move to a Kirchstetten, a rural village in Austria around the same time Britten and Pears moved to The Red House. He lived there with his partner Chester Kallmann, and as Sandra Mayer writes,

Auden in Austria defied categorisation and took full advantage of the liberating potential of his cultural, social, linguistic, and sexual outsiderdom, which freed him from any pressures to fit in and observe the stifling rules and conventions of village life. Paradoxically, the small scale and the provincial provided him with a considerable degree of licence that condoned the foibles of the eccentric foreigner and his ‘housekeeper’.

With their artistic careers and international reputations Britten and Pears, similarly, were perhaps seen as sufficiently ‘other’ to be afforded a certain indulgence that they may not have been permitted otherwise. But whatever the case, for Britten this acceptance was absolutely crucial. Accepting the Freedom of Aldeburgh in 1962 Britten movingly said,

As I understand it, this honour is not given because of a reputation. . .it is – dare I say it? – because you really do know me, and accept me as one of yourselves, as a useful part of the Borough – and this is, I think, the highest possible compliment for an artist.

Aldeburgh gave Britten the domestic security he needed, and at the same time allowed his, and Pears’, artistic ambitions to flourish. The ‘personality’ of The Red House Britten and Pears managed to achieve a remarkable equilibrium, which is something that visitors to the house today can detect. It was a comfortable retreat, serving a brilliant artistic mind; an aesthetically pleasing surrounding for a vibrant and sensitive performing artist – and a safe, loving home, against the odds.

The Red House, photographed in October 2020 (Photographer: Beki Smith)