Imogen Holst: In Her Own Orbit

As her Aldeburgh home opens to the public for the first time in a decade, Hannah Lack remembers an unsung hero of 20th century music. Never in the public eye like her father, Gustav Holst, or her long term collaborator, Benjamin Britten, Imogen Holst chose to live alone, in the modernist gem of a home designed for her by the architect, Cadbury Brown. However in her woollen cardigans and sensible skirts, she championed music for all, in all its forms, and her work touched the lives of all she met...

When Imogen Holst was born in 1907, her father announced the news not in words, but with a handful of crochets and quavers:

The only child of Gustav Holst, the composer most feted for The Planets suite, musicians in Holst’s family stretched back four generations to her Riga-born great-great-grandfather, who taught the harp to the Imperial Russian court in St Petersburg. But if her life seemed preordained to be a musical one, the expansive form it took was entirely down to her own, singular personality.

Imogen Holst's house at 9, Church Walk, Aldeburgh

Composer, teacher, conductor, arranger, dancer and knitter-together of people, Holst was an indefatigable champion of music in all guises, whether performed by the Vienna Philharmonic or in a country pub on a couple of tin spoons. For all her extensive musical training, from the sixteenth century counterpoint she studied in Switzerland to the boatmen songs she learned in India, she was open-minded in her belief that music could, and should, be played by all.

Her house was designed by H.T. Cadbury-Brown, the modernist architect best known for the Royal College of Art building. Its combination of elegance and practicality suiting her perfectly

As a toddler, Holst sat on her father’s lap, striking the piano’s black notes as he played Bach, singing the folk songs he taught her and dancing to his compositions. (When faced with a difficult piece to untangle as an adult, her first impulse was still to get up and dance to it.) The Holst family had Swedish, Latvian and German roots, but they’d emigrated to the UK by the time Holst came along, and she grew up in an airy Thames-side house in Barnes. (There’s a blue plaque to Gustav affixed to its façade today.) Holst debuted her first compositions at school aged 11 and later followed in her father’s footsteps by winning a scholarship to the Royal College of Music. In 1930, she was awarded a £100 travelling grant that allowed her to embark on a year-long musical odyssey through Europe from Scandinavia to Sicily: she took in modern Czech opera in Prague and Tzigane musicians in Budapest, string quartets in Berlin and concerts at Milan’s La Scala, her interests only seeming to widen the more she encountered. As a member of the English Folk Dance Society she also toured the length of Canada and the East Coast of the US, performing multiple duties with characteristic enthusiasm, first playing piano accompaniment, then racing to the stage for some nimble footwork in a country dance.

As a child, Imogen Holst (centre) danced to her father Gustav Holst's compositions. When faced with a difficult piece to untangle as an adult, her first impulse was still to get up and dance to it. Photographer unknown

But at the outbreak of the second world war, Holst focused her musical gifts closer to home – in 1939 she joined the Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts (CEMA), a morale-boosting initiative that set out to create “opportunities for hearing good music and the enjoyment of the arts,” during wartime. Holst was allocated a swathe of southwest England, a shoestring budget and the rather vague direction “to go where we liked and do what we liked when we got there”[1]. For three years she travelled countless miles and shared equally incalculable cups of tea across Somerset, Devon and Cornwall, meeting and supporting a cornucopia of unlikely amateur musicians: a village grocer who conducted a madrigal choir in the room behind his shop, a violin-playing postal worker who founded an orchestra in the ironmonger’s, a market gardener with a passion for sixteenth-century German recorder music.

The spot was initially earmarked for Britten's festival opera house. When those plans went awry, Cadbury-Brown and his wife Betty built their own, Japanese-influenced house on the site and a smaller jewel of a home for Holst in its garden

Holst’s time on the road revealed her extraordinary talent for connecting a community through music, marshalling evacuees and schoolchildren, retirees and housekeepers into motley musical troupes

In one Somerset village her journal describes an orchestra consisting of three mouth organs, two toy drums and a couple of spoons tied together with string. To Holst’s democratic ear, “this last was played with an astonishingly good sense of rhythm.” [2] Despite the arduous travel, often on foot or bicycle with a suitcase strapped to her shoulders, Holst’s time on the road revealed her extraordinary talent for connecting a community through music, marshalling evacuees and schoolchildren, retirees and housekeepers into motley musical troupes: “I soon discovered that ‘organising’ was not as formidable as it sounded and it mostly consisted of making a lot of new friends,” she wrote [3]. From those beginnings by an enterprising group of “missionary-minded spinsters” [4] as Holst described it, the CEMA went on to grow into what is today’s Arts Council.

Image gallery

Soon after, in 1942, Holst participated in the early days of another pivotal institution when she began running the music programme at Dartington, a crumbling medieval hall and sprawling grounds in Devon that housed the radical, utopian-minded vision of philanthropists Dorothy and Leonard Elmhirst. Holding experimental, progressive classes in the vein of Black Mountain College across the Atlantic, Holst’s unorthodox composition and choral lessons had no formal exams and swerved textbooks in favour of learning by doing. Classes were extended not only to students but the local community, wounded soldiers and anyone else who happened to drop by. “We would sit around with an instrument in our hands that we didn’t know how to play – the noise was horrendous,” [5] she remembered cheerily; she was particularly pleased to recruit a police constable from nearby Totnes to lend his bass voice to her regular Friday singing evenings in Dartington’s vaulted Great Hall.

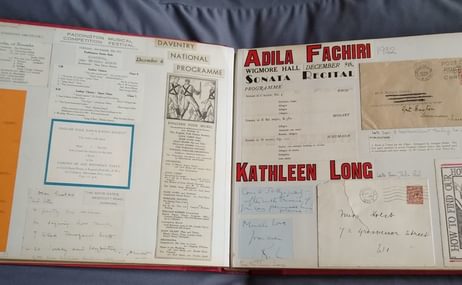

Over the years, the college attracted some of the greatest artists and thinkers of the 20th century, from Ravi Shankar and Aldous Huxley to John Cage and Benjamin Britten – and when Holst met the latter there in 1943, a friendship and working relationship was ignited that would profoundly shape her future. It was Britten who invited Holst to Aldeburgh in 1952 to help organise the festival he had founded four years earlier; she accepted and stayed for the rest of her life, becoming Britten’s musical assistant, a co-director of the festival and a regular presence on the town’s pebbly seafront, clad in sensible woollen cardigan and cotton skirt, her sandy hair twisted into a neat bun as she took miles-long early morning walks that endured regardless of the seasons.

Peter Pears, Benjamin Britten and Imogen Holst. 1954, photographer unknown

Holst’s uncanny ability to make things happen, the persuasiveness of her lively blue eyes, found its apex in the life of the Aldeburgh Festival.

The journal Holst kept between 1952 and 1954 – peppered with exuberant exclamation marks and underlinings – catalogues everything from festival tussles to Britten’s wayward driving of his Rolls. But most of all it reveals Holst’s tireless devotion to the composer, despite her often candidly expressed opinions. (“My tactlessness is what I’m employed for and so must risk everything when music is at stake,” [6] she wrote.)

Line drawing of Imogen Holst by Cecil Beaton

There is a 1979 pencil drawing of Holst by Cecil Beaton that captures in a few quick strokes her sharply intelligent face – looking at that portrait, it’s easy to understand Britten’s pleasure and relief when she arrived to take her post. Holst’s uncanny ability to make things happen, the persuasiveness of her lively blue eyes, found its apex in the life of the Aldeburgh Festival.

Imogen Host at Church Walk. Photo by Edward Morgan

Yet that businesslike side was just one of many interlocking selves. Her light-filled, modernist bungalow at 9 Church Walk in Aldeburgh, Holst’s home between 1962 and her death in 1984, is full of details that conjure her idiosyncrasies and contradictions. She was a deeply private person who lived alone all her life, yet so enjoyed being around others that “even committee meetings turn into parties,” as she merrily put it in a 1972 edition of Desert Island Discs. She was a musician who for years refused to own a gramophone, a supremely capable person who admitted her culinary skills extended only to strong coffee and a hardboiled egg.

In the bungalow’s north corner, her office – with floor-to-ceiling window facing a lush garden of lightly managed disorder – has a special resonance as the place Holst began to compose her own works again

Her house was designed by H.T. Cadbury-Brown, the modernist architect best known for the Royal College of Art building adjacent to the Albert Hall in Kensington. Situated on a patch of ground near The Red House, the Aldeburgh spot was initially earmarked for a festival opera house. When those plans went awry, Cadbury-Brown and his wife Betty built their own, Japanese-influenced house on the site and a smaller jewel of a home for Holst in its garden, its combination of elegance and practicality suiting her perfectly. For the rest of her life, her rent consisted only of a crate of wine for the couple at Christmas, and a steady supply of Aldeburgh Festival tickets.

Holst admitted her culinary skills extended only to strong coffee and a hardboiled egg

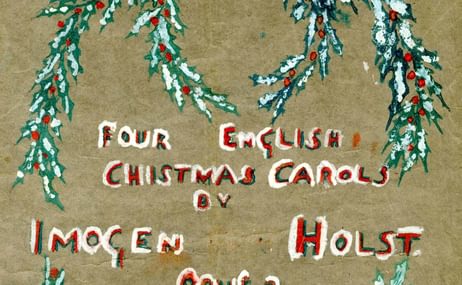

Never particularly materialistic (when Britten left her a bequest in his will, she handed it out to “several intelligent children, aged 10-13” [7]), inside the one-bedroom bungalow a few key, talismanic possessions remain: There’s Holst’s well-travelled conductor’s baton – she was one of the first women to conduct military and brass bands, and brought a dancer’s flair to the task; a collection of handbells on a shelf that nod to her love of ringers and the works she composed for them; and a soundproofed music room with piano that ensured the many hours she spent listening to classical Indian ragas didn’t disturb the neighbours. (In 1950, she had spent two months at Santiniketan University in West Bengal learning Indian dance and notation – she reciprocated by performing a Romanian sword dance among other European folk steps.)

Image gallery

A gallery slider

A collection of handbells on a shelf nod to her love of ringers and the works she composed for them.

A soundproofed music room with piano that ensured the many hours she spent listening to classical Indian ragas didn’t disturb the neighbours

Holst’s well-travelled conductor’s baton – she was one of the first women to conduct military and brass bands, and brought a dancer’s flair to the task

A capacious oak cupboard belonging to her father still occupies a corner of the living room – formerly packed with his manuscripts, it’s a reminder of Holst’s lifelong dedication to her father’s legacy, as well as the two rigorous, clear-eyed biographies she wrote illuminating Gustav and his work. But in the bungalow’s north corner, her office – with floor-to-ceiling window facing a lush garden of lightly managed disorder – has a special resonance as the place Holst began to compose her own works again. After so many years of allegiance to others – both to her father, and as invaluable musical assistant to Britten – this hideaway marked a flowering of compositions, including Deben Calendar for the Woodbridge Orchestral Society in 1977 and in 1982, String Quintet for the Cricklade Festival, reigniting her talents as a composer in her own right. Still, she didn’t confine herself to music: in a 1980 essay titled Advantages of Being Seventy, Holst noted she now had more time for “learning elementary arithmetic or memorising Shakespeare sonnets or beginning Russian grammar.” [8]

Image gallery

A gallery slider

A capacious oak cupboard belonging to her father still occupies a corner of the living room – formerly packed with his manuscripts, it’s a reminder of Holst’s lifelong dedication to her father’s legacy

A capacious oak cupboard belonging to her father still occupies a corner of the living room – formerly packed with his manuscripts, it’s a reminder of Holst’s lifelong dedication to her father’s legacy

A capacious oak cupboard belonging to her father still occupies a corner of the living room – formerly packed with his manuscripts, it’s a reminder of Holst’s lifelong dedication to her father’s legacy

Perhaps it tends to be the single-minded who are rewarded the blue plaques. But Holst, with her restless, roving curiosity had a gift for planting seeds that continue to sprout and branch today. Her haven at 9 Church Walk is no exception; it’s now used for visiting musicians in need of the space and peace to work on their own projects. Desiring as she did music for the many rather than the few, Holst’s was a life lived largely, often in the service of others, but above all in the service of music. She had periodically suffered from neuritis throughout her life, health problems that had prevented her from pursuing early dreams of becoming a professional dancer or performing musician herself. Yet her desire to share her passion for music remained undimmed. Undeterred, Holst found a way to dance all the same, in her own inimitable way.

Photography by Sarah Letchford

The house is now closed. Sign up to our newsletter to find out about future openings of Imogen Holst's home. Learn more about Imogen Holst in this film by Dr Lucy Walker. A comprehensive biography: Imogen Holst: A Life in Music, is edited by Christopher Grogan, and published by Boydell Press.

Footnotes

[1] Making Music, no.2, October 1946

[2] Arts Enquiry report, 24 April 1940

[3] Making Music, no.2, October 1946

[4] Desert Island Discs, 20 Oct 1972, BBC Radio 4. (Holst’s favourite track was Rondo by Henry Purcell, her choice of book was Kilvert’s Diary 1870-1879, and her luxury was a spy-glass.)

[5] Peter Cox and Jack Dobbs, Imogen Holst at Dartington, Dartington, The Dartington Press, 1988

[6] Aldeburgh Diary, 9 Dec 1952

[7] Imogen Holst: A Life in Music, revised edition, edited by Christopher Grogan, pp.419

[8] Advantages of Being Seventy, Aldeburgh Festival Programme Book, 1980