An official history of the Aldeburgh Festival

The Aldeburgh Festival has been a pilgrimage for lovers of classical music and culture since 1948. Every June it brings together new commissions, world-premieres and international stars on the stretch of Suffolk Coast which so bewitched its co-founder, composer Benjamin Britten. Here Dr Nicholas Clark, Librarian at The Red House, looks back on the history of the Festival.

How did the Aldeburgh Festival start?

“Why not make our own Festival?” Peter Pears suggested when returning from an English Opera Group tour to Lucerne in 1947. “A modest Festival with a few concerts given by friends? Why not have an Aldeburgh Festival?” This idea grew partly from the rigours of touring, but it also evolved from a strong wish to bring culture to a community still suffering from the austerity of the Second World War. On their return from Switzerland Britten and English Opera Group producer Eric Crozier discussed the possibility with several of the town’s people, for the project would need a great deal of local help. Questions about where to hold concerts, how to accommodate visitors, how to recruit help, whether petrol rations would enable transportation of artists and audiences all had to be considered. Fidelity, Countess of Cranbrook chaired a committee that focussed on these practical matters as well as the vital means of attracting sponsorship. The then new Arts Council of Great Britain became a key source of financial help.

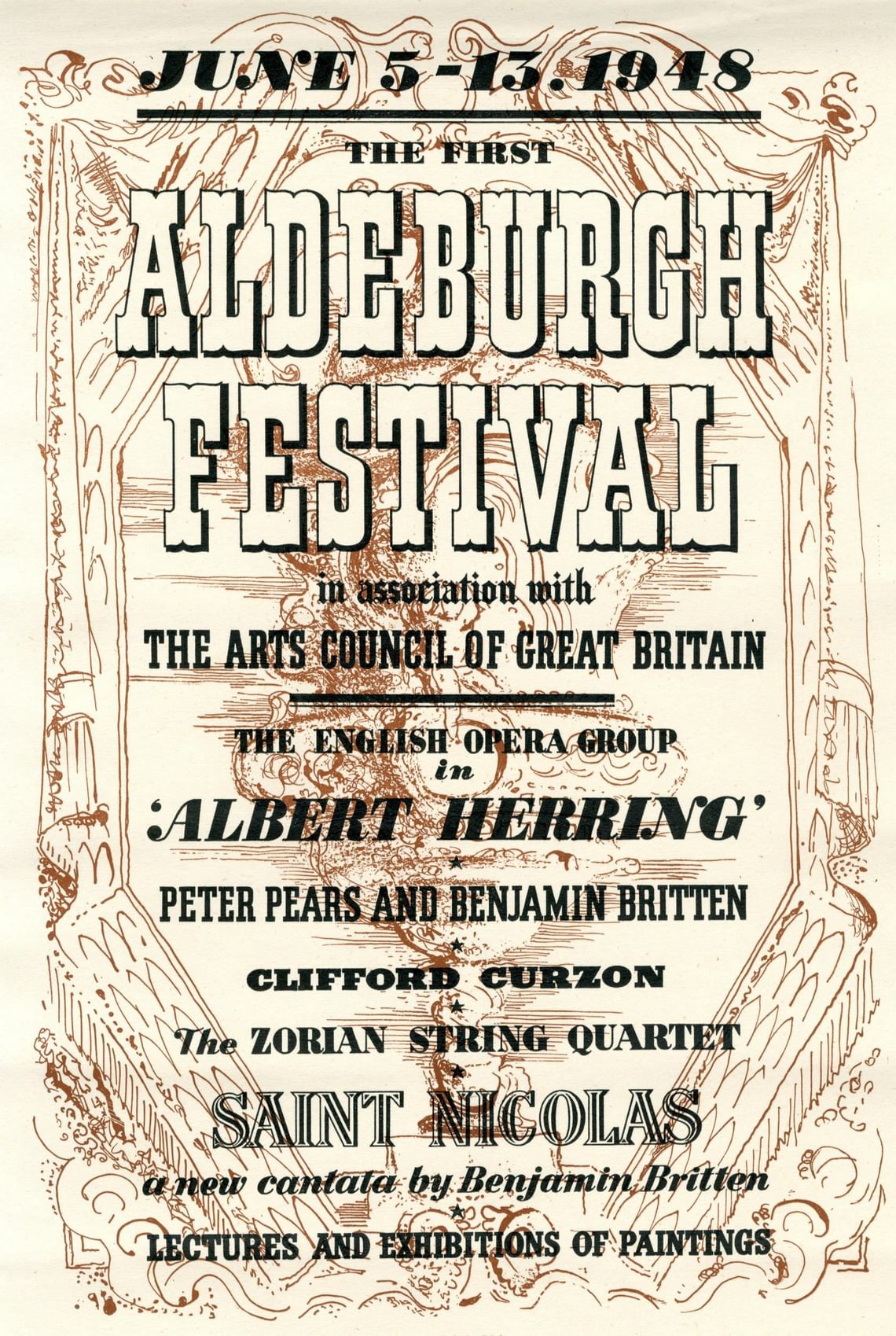

Flyer for the first Aldeburgh Festival, 1948

The first Aldeburgh Festivals

The first Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts began on the 5 June 1948. The programme for the week-long event included chamber and choral music, a staging of Britten’s opera Albert Herring at the Jubilee Hall and the first performance of his cantata Saint Nicolas at the Parish Church. Lectures were delivered by E.M. Forster on George Crabbe, Tyrone Guthrie on theatre and Sir Kenneth Clark on East Anglian painters. Exhibitions were mounted at private homes and in the Moot Hall. The Festival soon became an annual event on the artistic calendar, with this first Festival providing a model for the diversity of content that would become its hallmark.

Yehudi, Menuhin, Kathleen Ferrier, Dennis Brain, Clifford Curzon, and the Amadeus String Quartet are among those who performed during the Festival’s early years. A number of musicians established an on-going association, particularly singers and musicians connected with the English Opera Group. Writers L. P. Hartley, Arthur Ransome, Angus Wilson, Dame Edith Sitwell came either to read or deliver lectures. The visual arts, vital to Britten and Pears’ personal lives, were highlighted through exhibitions of Constable and Gainsborough, John Piper, Georg Ehrlich, Elisabeth Frink and John Nash. Film was another component of the Festival, with classics of the screen by Chaplin or the Marx Brothers and documentaries on local history, flora and fauna. Music Concrète could be the focus of one programme, whereas the Aldeburgh Players’ production of the comedy The Dumb Wife of Cheapside (featuring the Aldeburgh Scouts as ‘the Horse’) might be another.

Britten, Imogen Holst and Pears, early 1950s Photo: Unidentified

Artistic director, Imogen Holst

Culture that was both familiar and new, national and international, lost and rediscovered was offered to audiences. From the Festival’s beginning, music by young composers was invariably played in programmes that also included pieces by Bach or Purcell, Mozart or Tchaikovsky. Themed concerts became a specialism of Imogen Holst, Britten’s assistant, who became an artistic director in 1956. Under her initiative programmes devoted to early music, often focussing on a specific composer or era, were scheduled for late evening and would take place amid the atmospheric ambiance of the Parish Church.

The Burning Fiery Furnace, Orford Church 1966 Photo: John Richardson

A concert hall for Aldeburgh Festival

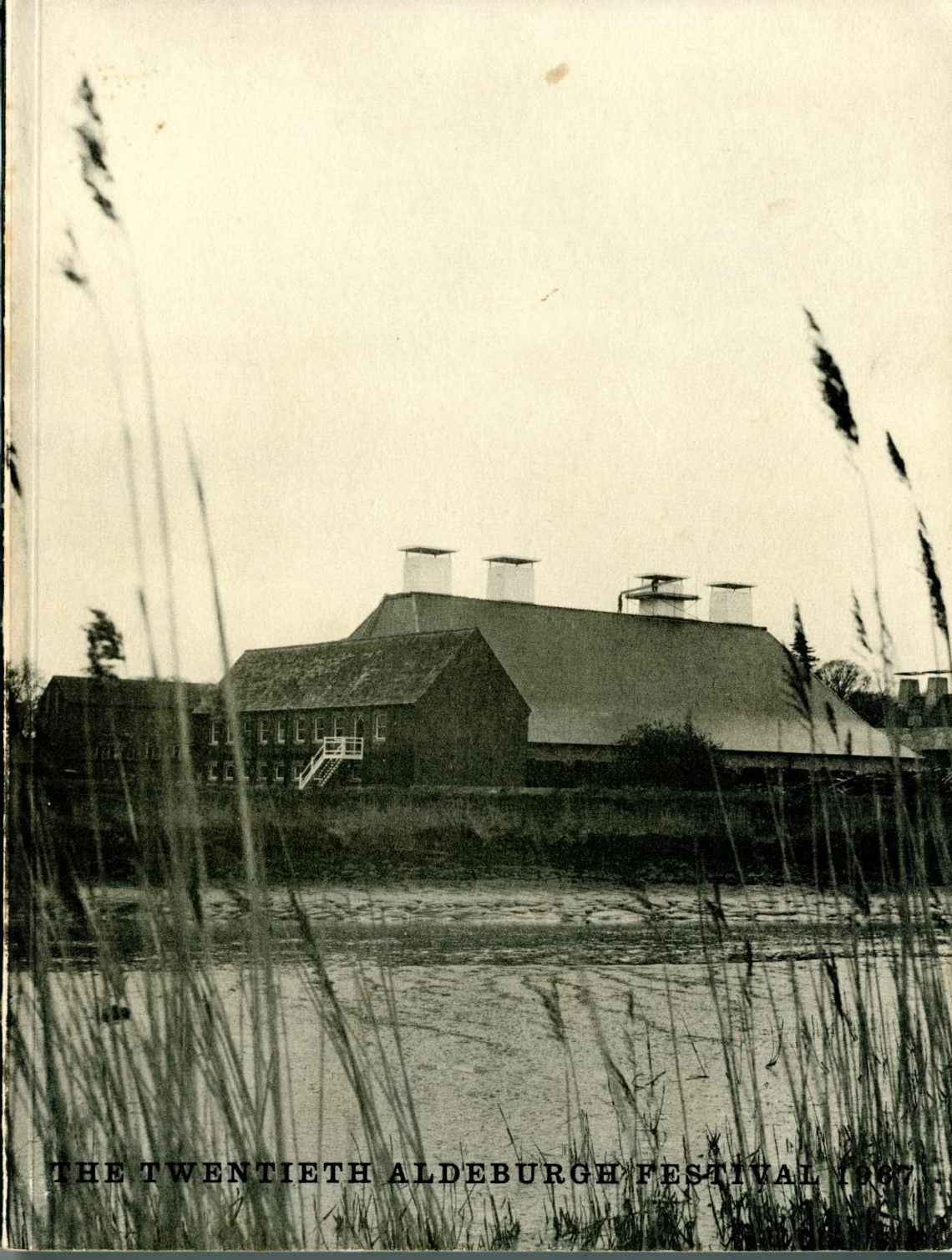

Churches further afield in Framlingham and Blythburgh also proved admirable concert venues. Orford Church saw the premiere of Britten’s community opera Noye’s Fludde (1958) and all three of his Church Parables. However, a dedicated concert hall, which had long been Britten’s wish, proved elusive. Costs prevented the construction of such a building in Aldeburgh, but fate intervened in the early 1960s. Festival Manager Stephen Reiss envisaged a new use for the Maltings at Snape, which had recently ceased operations as a barley-malting warehouse. The wood and brick interior was converted into a concert hall, giving the building a new purpose. It allowed seating for nearly 1,000 people, and a large stage that could accommodate a chorus and symphony orchestra. Queen Elizabeth II officially opened the Maltings on the 2 June 1967. This was followed by a choral and orchestral concert that demonstrated the hall’s acoustic. Its adaptability was evident in the staging that year of a new production of Britten’s 1960 opera A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Programme book for the 1967 Aldeburgh Festival

On the opening night of the 1969 Festival a fire, probably the result of an electrical fault, destroyed the new hall. However, it did not stop the music. A combination of goodwill and ingenuity that supported the Festival in the past was brought to bear again. Only one concert that year suffered cancellation while the rest of the programme continued with minimum alteration in hastily arranged new venues.

Stage set for Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Snape Maltings, 1967 Photo: John Richardson

Artistic direction

By June 1970 the Maltings had been rebuilt paving the way in the ensuing years for a new generation of artists. Cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, singers James Bowman, John Shirley-Quirk and Janet Baker and pianist Murray Perahia all performed there under the continuing artistic direction of Britten and Pears. Following their deaths artistic direction was handed to musicians who knew and worked with both men: these included conductors Philip Ledger and Steuart Bedford, composers Colin Matthews and Oliver Knussen. Subsequent directors have, in turn, encouraged a new stream of regular performers.

Britten’s opera Death in Venice premiered at the 1973 Festival, with Peter Pears as Gustav von Aschenbach Photo: Nigel Luckhurst

Peter Grimes

Innovation and versatility remain central to Aldeburgh. In 2013, Britten’s centenary year, his opera Peter Grimes was staged on Aldeburgh beach – the first time such an event had ever taken place. A dress rehearsal was performed especially for local residents who saw their seafront transformed into an opera house. The Jubilee Hall, Parish Church, Blythburgh, the Maltings and the Suffolk landscape remain key venues for performance but recent developments at the Maltings site, like the Britten Studio, are also engaging concert spaces.

The Aldeburgh Festival today

Film, art, nature, literature and music past and present are still the lifeblood of the Festival, now part of the charity Britten Pears Arts. It continues to witness first performances of new work – a tradition seen in Britten’s Songs and Proverbs of William Blake (1965), the opera Death in Venice (1973), and cantata Phaedra (1976), all of which were premiered at Aldeburgh, as were pieces by Aaron Copland, Lennox Berkeley, Richard Rodney Bennett, Harrison Birtwistle, Thea Musgrave, and Robin Holloway. And the tradition continues with recent music by composers such as Sadie Harrison, Cassandra Miller, Gavin Higgins and Sarah Angliss.

The Festival also nurtures future talent through teaching. A school founded by Britten and Pears in 1972, now known as the Britten Pears Young Artist Programme, allows students to participate in masterclasses under the direction of renowned instructors and to perform on stage in Festival concerts with world-class artists and conductors.

The “modest festival” Pears envisaged nearly eight decades ago still has as its focus a passion for supporting music and the arts and making them useful in the community.

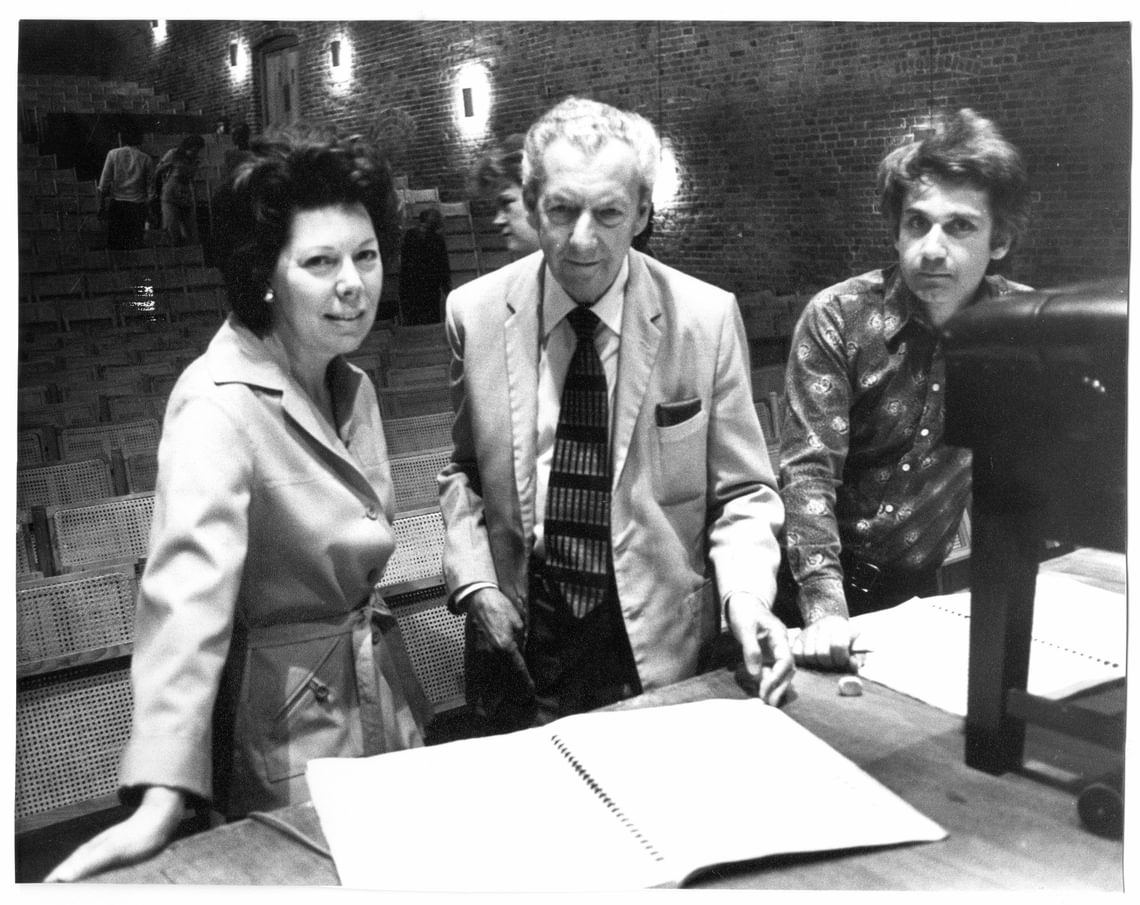

Janet Baker, Rita Thomson, Britten and Steuart Bedford during rehearsals at Snape Maltings for Britten’s cantata Phaedra, premiered at the Aldeburgh Festival 16 June 1976. Photo: Nigel Luckhurst

Dr Nicholas Clark has written on various aspects of Britten and Pears’s lives and work, including the history of their library, the literary influences on Britten’s music, set designs for opera, and how their letters to one another record their nearly 40-year relationship. He is the co-editor of My Beloved Man, The Letters of Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears. He is librarian at The Red House.